How much does a person have to roll down the windows to be COVID safe in a car? And is there a “right” or “wrong” window?

A study by a team of Brown University researchers used computer models to find the best window combinations for optimal airflow.

The study started with some assumptions, so let’s set the scene. The driver and passenger are sitting as far away from each as possible, on an angle. And both are wearing masks.

The best option seems obvious: open all of the windows, all of the way. It’s the closest to being outdoors.

This option increases the number of air changes inside the car, which helps to reduce the overall concentration of aerosols that may cause COVID-19. The configuration forms two independent air flows, keeping the driver and rider’s air as separate as possible.

But this can be unfavorable in cold or wet conditions.

Other configurations can provide benefits too.

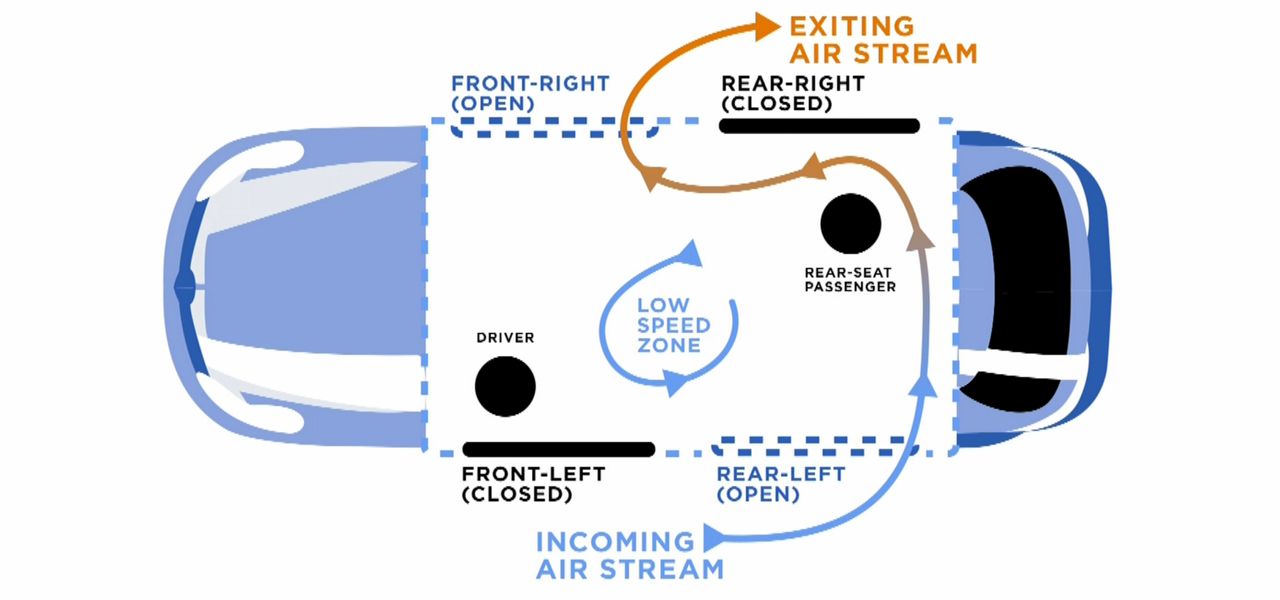

The second best option is opening the window opposite each person.

This gives the air a place to come in and go out of, and flushes it out of the middle of the cabin, while building a kind of air curtain between the driver and the rider.

Plus, it’s more comfortable.

The worst option is opening the windows next to the driver and passenger.

This does the opposite of the best configuration. Instead of creating an air curtain, it creates air flow from the driver to passenger that could increase the transport COVID particles. And there's more of a build up of particles because the air isn’t getting flushed out as much.

Opening the windows won’t bring the risk to zero, but anything helps.

“There’s always a potential risk,” said Brown PhD student, and one of the researchers, Asimanshu Das. “By at least going through this paper they can at least know we should not be in a car with all windows closed. To just increase the ventilation, open two windows. Of course it leads to some discomfort but at least you can reduce the risk.”

The study did have some limitations. It didn’t consider factors like someone sneezing or coughing, didn’t include data on longer car rides nor sitting in traffic. The study also did not explore only one window being open or different car types and models.