An answer to one of society’s biggest questions may be found in the youngest minds.

“She may fuss a little bit, if she fusses I'll try to get her to be much more entertained,” said Sonya Troller-Renfree, an assistant professor at Columbia University Teachers College.

Troller-Renfree stretched a bizarre looking cap over her infant daughter’s head— an array of tiny sponges, strung together by delicate wires like a futuristic spider’s web. The device was called an electroencephalogram or EEG cap (more on that later), and Troller-Renfree was eager to show us how it worked.

Troller-Renfree is part of a team of researchers led by Dr. Kimberly Noble, they are trying to prove that poverty impacts a child’s development, including their performance in school. Decades of research shows a strong correlation, but not direct causation.

“Although we have an abundance of evidence linking poverty to these different outcomes, we couldn't say for sure whether poverty was causing those different outcomes,” said Noble. She is the director of the Neurocognition Early Experience and Development (NEED) Lab at Teachers College.

Their hypothesis is that mothers with access to cash when they need it, raise babies with stronger brain development.

It was a welcome reprieve for mothers like Keturah Blunt. Last summer, Blunt had a new baby on the way, bringing joy, but also more stress.

“I was very stressed. I was depressed,” said Blunt. “My mom got really sick and then my pregnancy was progressing. I wound up becoming high risk, so work wasn't even an option at the time.”

Blunt moved into a shelter with her older two children and fiance. “I was extremely upset because my independence and my self-sufficiency is what I strived for ever since being a young lady,” said Blunt.

Through word of mouth, she learned of The Bridge Project, a program aimed at ending childhood poverty by giving new moms access to cash when they need it — no strings attached.

“The power of cash is that it's easy and it's flexible and it's empowering because it says, ‘We trust you to make the decision that's best for you, for your baby and for your family,’” said The Bridge Project Executive Director and Co-Founder Megha Agarwal.

The program is funded through the Monarch Foundation, which has teamed up with researchers at the University of Pennsylvania to help analyze the survey data mothers voluntarily provide.

There are two groups; mothers receive either $500 a month or $1,000 to spend on whatever they need. The money is transferred monthly to a debit card.

For some mothers, like Susan Erhirhie, the concept seemed unreal.

“I'm not used to people giving me free stuff,” said Erhirhie.

Erhirhie said though, she is grateful for the extra cash, which helps take away some of the stress of caring for her two small children.

“My brain is calculating, what is he going to wear tomorrow? Does he need a diaper? Do they need baby food? So the money helped me so much,” said Erhirhie.

The Bridge Project said in the first six months of the program participants receiving $1,000 dollars saw a 242% increase in their ability to keep more than $500 in their savings accounts. Mothers getting $500 a month saw a 28% increase in their ability to save. While mothers in the control group, who did not receive cash gifts, saw a 23% decrease in their savings. There was also a 63% increase in mothers accessing outside childcare.

“Once finances are like not a worry, it frees up your mind space to do so many other things,” said Blunt.

The Baby’s First Years Study is a different research project following 1,000 mother-child pairs in New York City, New Orleans, Omaha, Minneapolis and St. Paul. They are exploring whether giving mothers just $4,000 extra a year can make a difference.

“The basis of the Baby's First Years study is really to understand whether providing economic support would change children's trajectories,” said Noble.

They published results from the first year of research in early 2022 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) journal. What they found did not surprise them, but it did make waves.

Troller-Renfree put the EEG cap on her own infant daughter’s head to demonstrate how they have been gathering concrete evidence of the impact of cash gifts. We were unable to profile actual mother-child participants in an effort to preserve the integrity of the clinical trial.

The squiggly lines each correspond to one of the little recorders on the cap.

Mothers in the study were randomized into one of two groups; a high cash gift group receiving $333 a month and a low cash gift group receiving $25 dollars a month.

Those who agreed to participate brought their child in for regular visits, allowing their baby’s brains to be listened to.

“Just like how your voice goes into a microphone is the same idea as your brain activity going into these little recording sensors,” said Troller-Renfree.

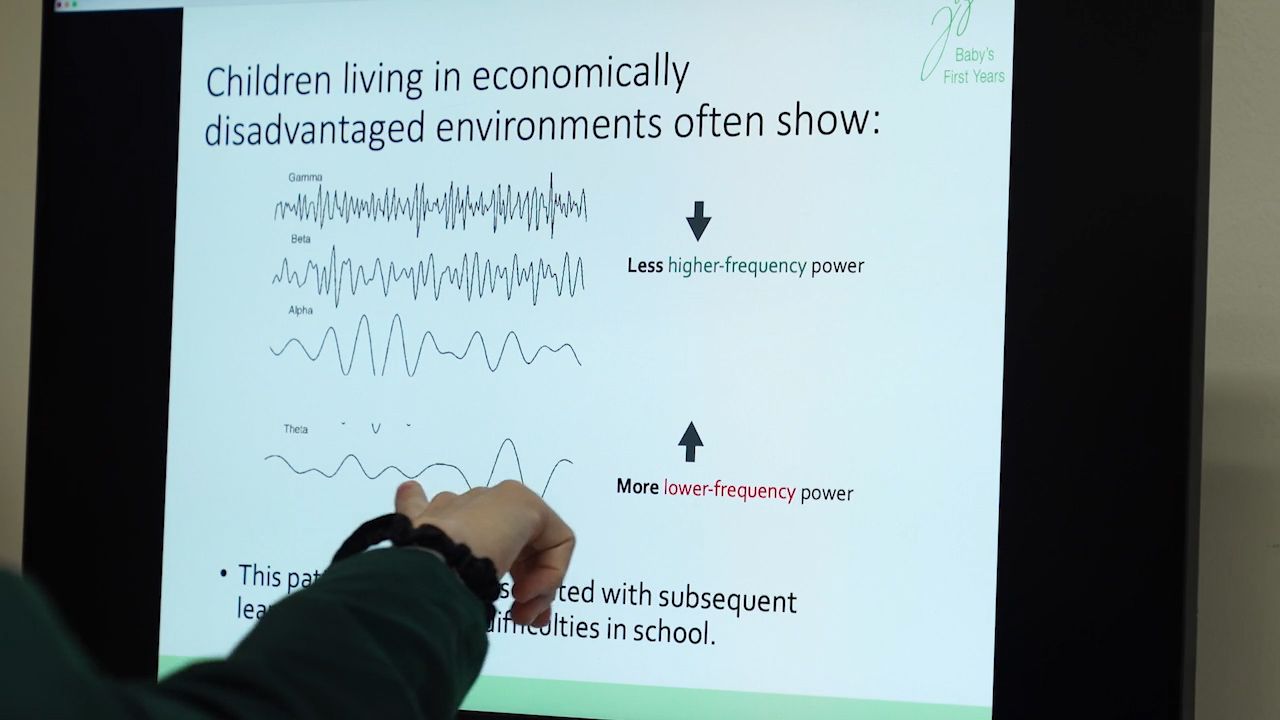

They are recording the speed of the childrens’ brain activity. They found that mothers who had access to more cash, did in fact have children who developed faster brain activity.

“It's a historic study. It's the first of its kind in the early childhood field,” said Dr. Hirokazu Yoshikawa, co-principal investigator in the Baby’s First Years study, and Professor of Globalization and Education and NYU Steinhardt.

Yoshikawa explained that fast brain activity is a sign a child’s brain is developing a sturdy foundation upon which to build necessary life skills.

“That fast paced brain activity that the program increased is associated with later language and cognitive development,” said Yoshikawa. “The kinds of things that we think of as early language skills, early social skills, early ability to comprehend the world.”

Yoshikawa and Noble took pains to show that it is the cash making the difference, not other factors in participants’ lives.

“The beauty of a randomized controlled trial is that, if you recruit a large enough group and you ensure that they're similar at baseline,” said Noble, “by actually changing family income, we can say, to what extent does this intervention cause these differences in outcomes.”

When mothers in the Baby's First Years study were surveyed, those in the high cash gift group echoed similar responses to The Bridge Project moms like Blunt, who said she noticed a difference in her own attitude. Blunt also reported that her kids were more affectionate, a change she attributes to changes in her own disposition.

“Once they see, mommy's a little happier, okay, Mommy is in a good mood, let's hang out with mom a little bit more,” said Blunt

“What we're finding is that parents are spending more time with their children, interacting with them, and they report higher rates of reading picture books with their child, singing songs, telling stories. These kinds of early learning activities,” said Yoshikawa.

Both studies have similar goals — to prove that giving unconditional cash transfers to parents who need it may be a relatively simple way to level the playing field.

“I always like to say you can't pull yourself up by your bootstraps if you don't even have boots. And what we're looking at in the United States is a lot of people that just don't have boots— they're fighting every single day to just try to find boots,” said Agarwal.

In all, The Bridge Project moms get at most $12,000 extra through the program each year, for three years.

“I think you'd be pretty hard pressed to find a place in the United States where you can live on $12,000 annually,” said Agarwal. “It's not really going to incentivize people to stop working. What it's actually doing is allowing people to access work in a stronger way.”

It is just the beginning of Baby’s First Years study. Researchers plan to follow families until the child is eight years old. In addition to brain waves they are also measuring mothers’ cortisol levels and epigenetics by collecting hair samples.

Ultimately, they hope their work will impact future policy decisions, transforming the landscape of social services and benefits.

“We're scientists, not advocates. So we very much look forward to disseminating the results of our work to policymakers and other audiences,” said Noble. “It's certainly our hope that it'll impact ongoing debates on the generosity of existing, as well as new social services and benefits, that affect millions of disadvantaged families.”

“There's an equity issue in the United States in the sense that public spending on children is much lower, it turns out, in the early childhood period than for primary or secondary school kids,” saidYoshikawa.

These experts said the health and flourishing of society starts with how kids develop.

“If you have stronger brain development, you feel more secure in your earliest days,” said Agarwal. “It impacts the way you show up at school, the way you show up at work, the way that you view your future, how you view your role as a part of society. So brain development, it's one small piece, but it impacts everything.”