Simpson Kalisher, 92, retired to Florida after a career as a professional photographer.

"He has some photographs in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum in New York," said his daughter, Amy Kalisher.

That's why Ms. Kalisher wasn’t surprised to learn Mr. Kalisher was contacted about a biographical profile. He was invited to be included in the next volume of Inspiring the Youth of America By Remington Registries, written by J. Alex Ficarra. The book's back cover explains it is a collection of biographies written "to build a better America from where it really matters – our youth."

"This was to benefit the youth of America," Ms. Kalisher said. "So it appeals to both his vanity and to his sense of civic duty. And all they are asking for is $14, so it was an easy yes for him."

What's the Difference Between Vanity Press Publications and a Reputable "Who's Who" Directory? The president and CEO of the Better Business Bureau of Metro New York explains.

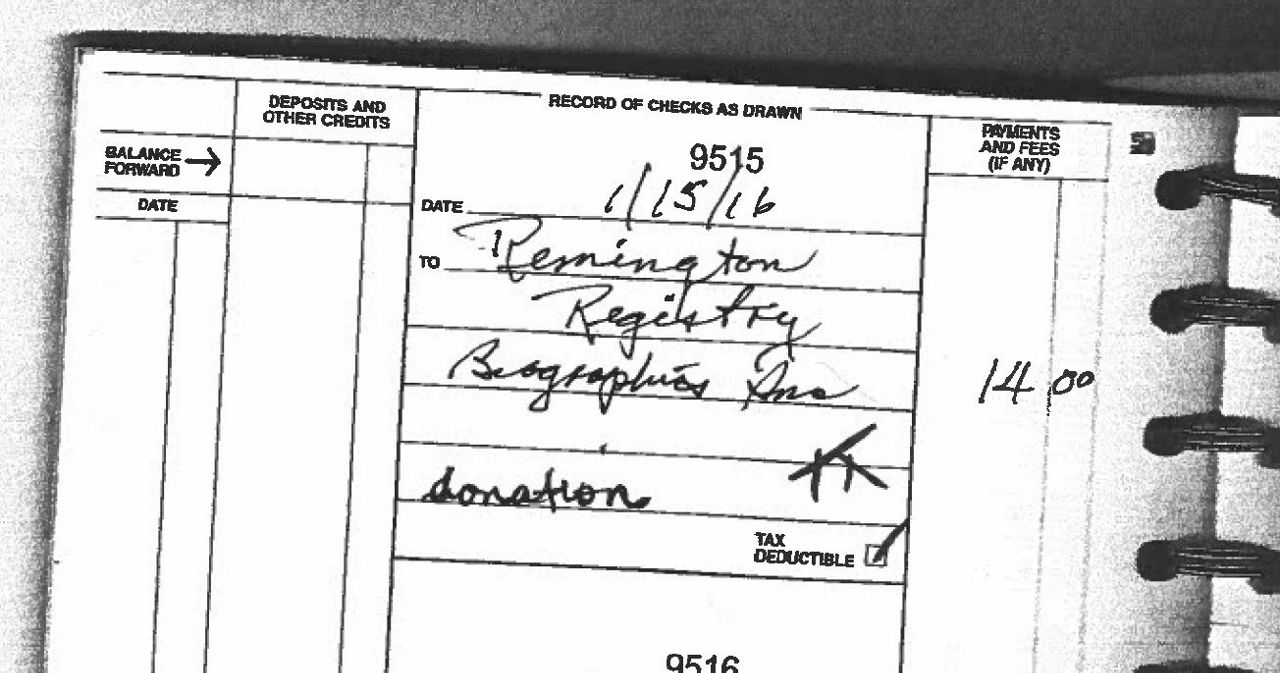

Ms. Kalisher, having taken over management of Mr. Kalisher’s finances, tracked down the processed $14 check in the online bank account. The check was made out to a company called Remington Biographies.

(Simpson Kalisher - photo of $14 check. Courtesy Kalisher Family)

"And then I looked a little bit more right around that same time period and I saw a large withdrawal," said Ms. Kalisher.

She discovered a second processed check, but it didn't look like the checks in her father's checkbook. It was an electronic check generated using her father's account numbers and address, made payable to Remington Biographies, in the amount of $1,825.

(Simpson Kalisher - photo of $1,825 check. Courtesy Kalisher Family)

"It wasn't his handwriting, and yet it was coming out of his account, it had his bank numbers on it, and the money had been withdrawn," Kalisher said.

Ms. Kalisher immediately notified Chase Bank, but before the account was closed, a third electronic check in February was processed for $3,250.

(Simpson Kalisher - photo of $3,250 check. Courtesy Kalisher Family)

"His income is like $1,400 a month, Social Security, so that's very significant," Ms. Kalisher said.

Mr. Kalisher ended up paying $5,000 for the biography, far more than the $14 donation he thought was required.

An investigation revealed the Kalishers were not alone in this experience. Five people from around the country filed police reports or complaints with the New York attorney general's office after they said Remington Biographies withdrew thousands of dollars using electronic checks.

(Letter from William France. Courtesy Blodgett Family)

In February, Stewart Manville of White Plains, New York filed a complaint with the New York attorney general's office when Remington took $3,700 using electronic checks.

(Letter from Stewart Manville to Remington. Courtesy Manville Estate.)

(Stewart Manville checks. Courtesy Manville Estate)

Across the country, Elsie Blodgett in Stockton, California, filed a police report in November because $5,900 was taken from her account using electronic checks made payable to Remington Biographies.

(Elsie Blodgett checks. Courtesy Blodgett Family)

And Dr. Frederick McAlpine, of Natick, Massachusetts, also filed a police report in January 2017 when more than $7,000 was taken from his accounts using electronic checks.

(Frederick McAlpine checks. Courtesy McAlpine Family.)

(McAlpine's check registry shows a $14 check marked as donation with check number 9515. The electronic checks generated with his account information used check numbers later in the sequence - 9593, 9643, 9618, and 9668. But the McAlpines' records show they wrote the checks with those numbers from their own checkbook to other entities, like the AARP and National Geographic. Courtesy McAlpine Family.)

In all, these five people say Remington Biographies solicited personal checks for $14, duplicated the check numbers and took their money without authorization totaling more than $26,000. Though complaints are filed with various local authorities, no criminal charges have been filed as of this writing.

Former FBI Agent Steve Surowitz explains how law enforcement could determine whether a misunderstanding involving payment could turn into a crime.

Attempts to reach Remington Biographies' CEO John Ficarra, and author of the book, by phone and email were unsuccessful.

A visit to Remington's office address listed on its own mailings and registered with the state reveal a two-story home in Southampton, New York. Three cars and a boat are parked in the driveway.

When no one answered the door, we called and got Ficcara on the phone.

We invited Ficarra to join us outside and talk about the complaints lodged by the five people. He refused, but answered many questions, like whether he documented authorization prior withdrawing thousands of dollars from checking accounts using electronic checks.

"The law says we can have verbal confirmation, OK, so sometimes verbal confirmation is as good as any type of written documentation," said Ficarra. "We always have verbal confirmation. Always."

But we pointed out that the five people we found dispute authorizing withdrawals, referencing their police reports and complaints to authorities.

"We deal with a lot of senior citizens. And obviously that's not easy to do," Ficarra said. "But I apologize if anyone was unhappy."

He insisted that these people have been refunded. And it's true. Four of the five were refunded, but refunds came from their banks, not from Remington.

And Jerry Olderman of Bedford, Massachusetts never got a refund for the $4,025 taken from his account. He filed a police report. Again, no criminal charges have been filed.

"I mean, you're dealing with an 85-year-old man. You know that?" Ficarra said. “You're dealing with a man that's 85 years old and he's capable of saying anything."

Only two people saw biographies published. Elsie Blodgett's two-page biography cost $5,900. Dr. Frederick McAlpine's two-page biography cost $7,400.

Amy and Simpson Kalisher received the draft biography written about Mr. Kalisher's career, but they have no interest in seeing it published.

"I mean, if I had something of an opportunity to have a conversation with someone [at Remington] I would want to know why - why does this seem like a good way to use your ingenuity?, said Ms. Kalisher. "You can't assume that this is stealing for the rich to benefit the poor. It could be stealing from the poor to benefit the rich, you know."