After two decades as an ambitious police officer and another 15 in state and city politics, Eric Adams has achieved a lifelong goal: He is set to be the Democratic nominee for mayor of New York City.

So how did he win one of the closest, hardest-fought mayoral primaries in recent memory?

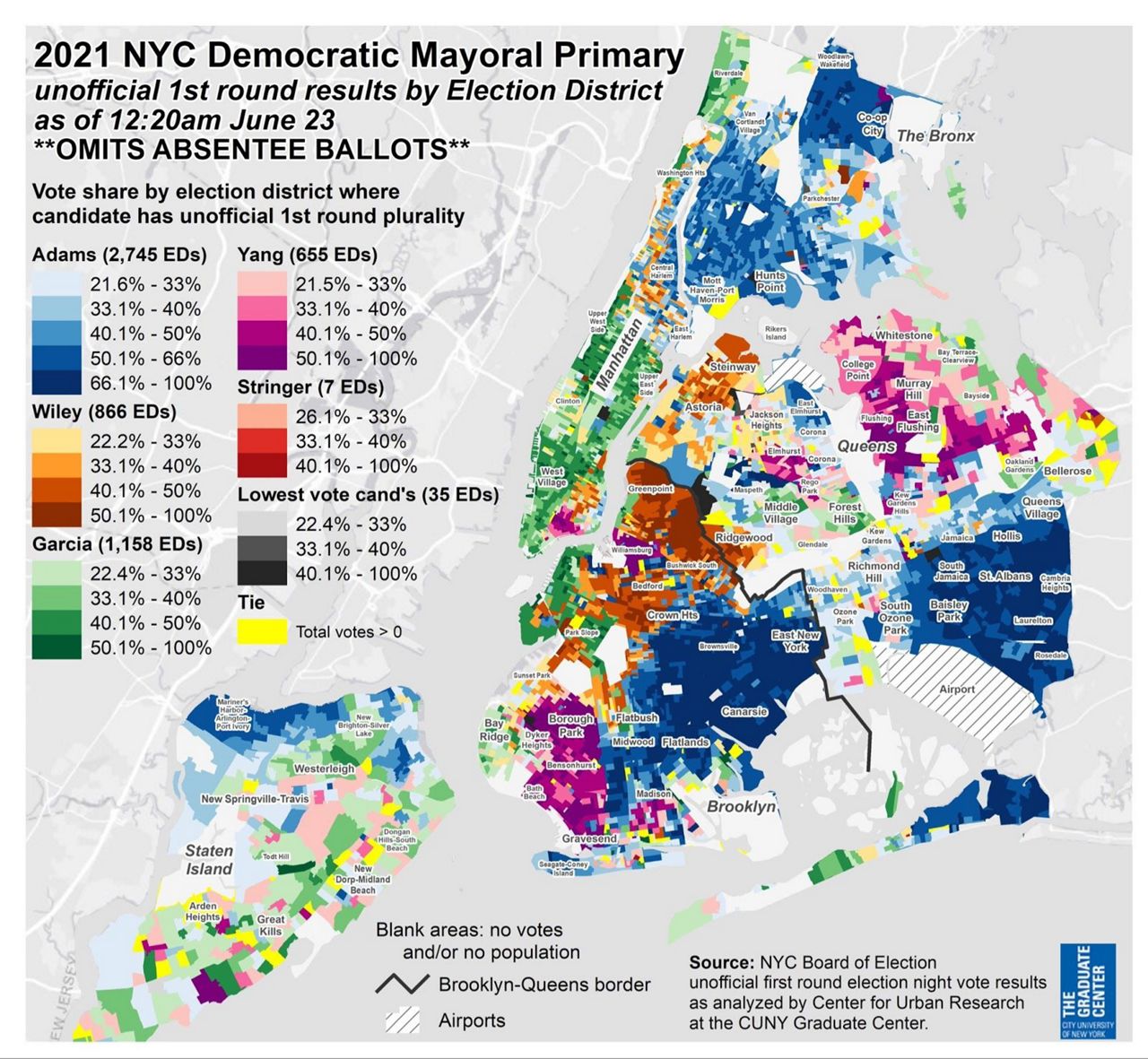

Adams relied on a traditional political game plan in a race that saw unexpectedly strong bids from three first-time city candidates: Kathryn Garcia, Maya Wiley and Andrew Yang. Adams earned support from working class voters with a focus on public safety and a fair economic recovery, and ran up the score in Black and Latino neighborhoods in the Bronx, Brooklyn and especially southeast Queens by securing key endorsements from local political leaders.

Garcia, who came in second, found support primarily in majority-white Manhattan neighborhoods, while Wiley, in third, was the candidate of the most progressive parts of Brooklyn.

Adams, however, won state Assembly districts in each borough — primarily working-class, majority non-white districts — enough to edge Garcia by one percentage point in a race that saw significant turnout compared with previous years.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that the working class folks made the difference in this election,” said Henry Garrido, the executive director of DC37, the city’s largest municipal union, which endorsed Adams.

Despite running in the first major city campaign after the unprecedented twin public health and economic crises caused by COVID-19, Adams relied on deep roots and name recognition in the areas that powered his win.

He grew up in Queens, giving him lifelong connections to residents in the borough’s eastern half, one of the most politically engaged Democratic parts of the state. As a police officer who was an outspoken critic of racist policing in majority Black and Latino neighborhoods he made friends with many Black officers who live in southeast Queens, and became a known quantity to Black and Latino New Yorkers around the city.

Those areas are home to much of the city’s essential workers, a demographic that Adams actively courted and said he identified with.

"They are me and I am them, that's what connected," Adams said on the day of the primary. "When they saw me they saw their brother, their aunt. They just saw this ordinary person."

As public safety became a watchword of the mayoral campaign amid a rise in crime, particularly shootings, Adams’ policing background became even more relevant. For many Black New Yorkers, his background as a police officer who was willing to call the NYPD “racist” has favorably identified him for decades with the movement to significantly reform, but not dismantle, policing in the city.

“Eric had a lot of name recognition because he was always out in the trenches, fighting for fairness in law enforcement agencies,” said Roslin Spigner, a district leader in southeast Queens who led organizing efforts there for the Adams campaign and who as a correction officer was a member of Adams’ organization, 100 Blacks in Law Enforcement Who Care. “He was an activist in uniform.”

The Adams campaign was careful to walk the fine line between calls for public safety and calls to reform the police, said Eli Valentin, a political analyst for Univision New York.

“That means having someone who is sensible to the fact that there's a history of over handedness when it comes to policing in New York,” he said. “Eric Adams was in the NYPD, he was a captain, but he was also at the forefront of being against police brutality.”

Adams’ long career in the public eye also helped him connect with working class voters broadly, Garrido said. At DC37’s candidate forums, Adams consistently had smart and effective answers for members asking how the mayoral hopefuls would address economic issues.

“His message was, ‘I not only hear your pain, I feel your pain, and I'm gonna do something about it,’ and he had the credibility of a lifetime of doing that,” Garrido said.

That extended to nuancing the issue of public safety, Garrido added, such as when Adams jumped on concerns from city workers about returning to daily commuting when Mayor Bill de Blasio reopened city offices, amid a spike in violent incidents on the subway.

Attaining the mayor’s office has been Adams’ goal since he was a police officer, and he got an early start seeking support in areas around the city where he saw his strongest showings.

Spigner said that for several years, Adams has been making regular trips to the Black working-class communities from Jamaica and Queens Village down to the Rockaways to ask for support. And, she added, “He didn't need a GPS to come to southeast Queens.”

In those areas, Adams’ work as an elected official preceded him, such as addressing bread-and-butter concerns of city residents, such as implementing healthier food in schools.

“That’s not the sexiest issue,” said Michael Lambert, a political consultant in Queens Village. “But it does speak to his ability to drive an issue to a desired outcome.”

In the spring, some elected officials who had previously endorsed Scott Stringer shifted their support to Adams after Stringer was accused of sexual misconduct.

In particular, having U.S. Rep. Adriano Espaillat switch his endorsement to Adams from Stringer was key to Adams’ eventually sweeping state Assembly districts in the Bronx, Valentin said, adding that by his calculations, Adams’ won 48% of Latino-speaking districts in the city.

Adams also made a strong play to secure endorsements from Orthodox Jewish leaders in Brooklyn after a largely successful bid for that support by Yang. Adams earned the support of the leadership of the powerful and politically active Satmar Hasidic community in Williamsburg, and polls suggested that while Yang had the edge in first-choice votes in the Hasidic world, Adams was a common second-choice pick.

His victory in the primary gives him a sure shot to win the November general election in majority-blue New York City. He’ll face Republican candidate Curtis Sliwa, the media personality and founder of the Guardian Angels watch group.

What remains to be seen for the working class voters who supported Adams is how he will both be true to and make best use of the relationships he has developed around the city as mayor. Adams has come under criticism during the election for taking more money than any other candidate from the real estate industry, and for being more effective at raising his public profile than accomplishing groundbreaking legislation.

“I think Eric will do a fantastic job. I pray that he does,” said Spigner. “Whatever he needs us to do as communities, the communities of New York City, we want to be there.”