East River Park is still here.

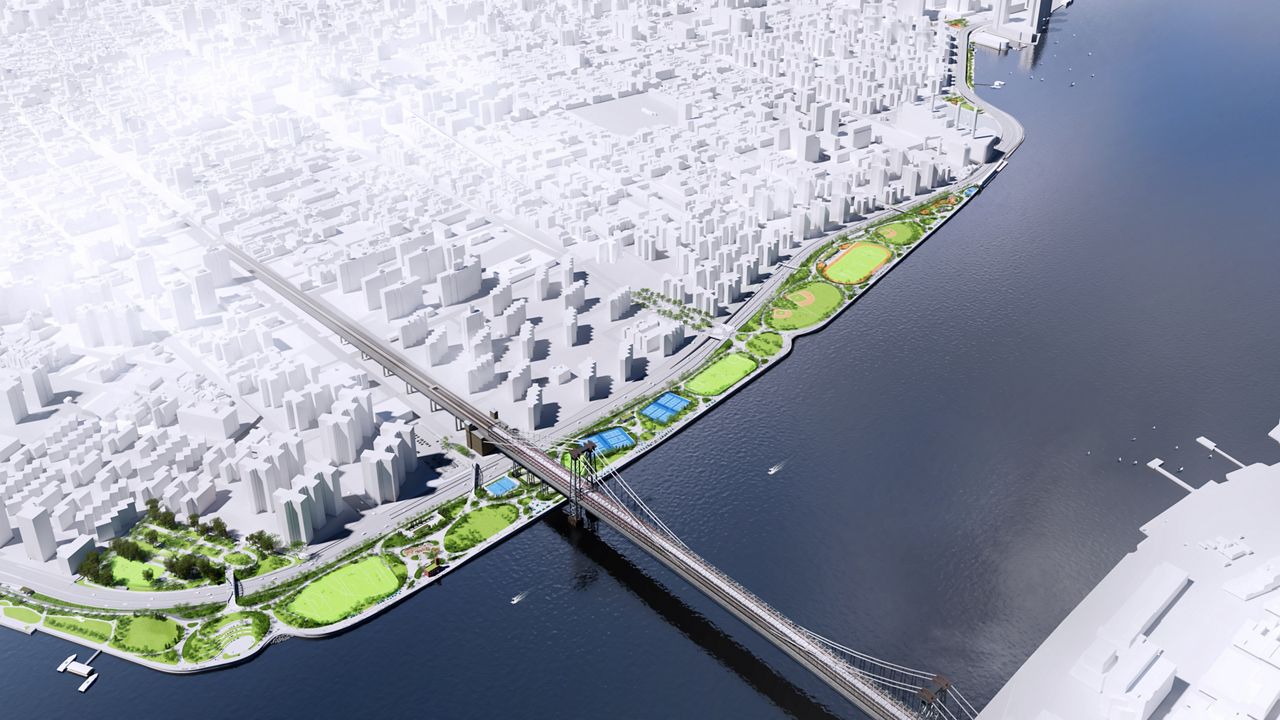

Earlier this year, the city told residents to expect construction to start in the spring on the $1.45 billion project to raise East River Park on top of eight feet of fill, part of the city’s flagship — and controversial — climate change resiliency project.

The construction crews never showed up. Little League games continued as scheduled. In September, a false alarm over what activists thought was the first tree removed during the park's demolition led to an emergency sit-in. According to the parks department, the tree was removed at least three years ago.

Yet climate change has not waited out the delays caused by the pandemic and contracting issues that the city says have held up construction. In the wake of Hurricane Ida, which caused flash floods that killed 13 people in the city, the city faces a laundry list of projects to adapt to a changing climate, most of them still in the planning phase.

East River Park remains the city’s most ambitious such project, and residents, politicians, policy experts and activists on both sides of it agree that there are important lessons to be learned for future resiliency measures. City officials now say construction will start in the park this fall.

The project has been dogged for years by concerns over lack of transparency, poor inter-agency communication and ongoing delays. The issues have fed frustration among residents, even as city officials say they are investing an unprecedented sum in a public park that primarily serves a low-income community in order to protect it against climate change for decades.

“It doesn't mean that the plan is not a good plan,” said Frank Avila-Goldman, a member of a local resident council that has consulted with the city on the plan. “It just means how it came about refuted trust.”

‘In the dead of night’

In the wake of Hurricane Sandy, New York City won a $335 million grant from the federal government through its Rebuild By Design competition, for a proposed flood barrier system for the southern end of Manhattan, called “The Big U.” The funding covered the section of the Big U that runs from the Lower East Side to East 25th Street, now called the East Side Coastal Resiliency Project.

The community then spent years working with city officials to figure out the details of the plan, as city agencies considered the problems inherent in working on a park sandwiched between a river and a busy highway.

The original vision called for a sloped park, rising up toward a flood wall that would run along the FDR Drive.

In 2018, however, local residents involved in the planning process say the city suddenly scrapped the plan, and then, with no warning, unveiled a new one: The de Blasio administration would completely demolish the current park and raise the entire area on eight feet — and more than a million tons — of fill.

The change seemed as if it happened “in the dead of night,” Avila-Goldman said. The sudden change sparked rumors in the community that the city was bowing to pressure from private developers or construction interests who wanted a more expensive project.

“They did not have one rendering, one idea or anything,” said Amy Chester, who ran the Rebuild By Design competition and is now managing director of the design consulting firm of the same name. “I think it would have taken one meeting to get buy-in from the community.”

It also sparked an enduring activist opposition, which views the fill as a potential environmental hazard, and is concerned that the raze-and-raise plan will destroy the park’s ecology.

“There were four years during which the city sat down with the community and worked up a plan,” said Kathryn Freed, a former City Council member who is a member of East River Park Action, an activist group that has fundraised for lawsuits against the plan. “Then almost overnight they brought in a single source contractor and brought in a new plan. They’re really flying by the seat of their pants.”

City officials said that there was no trickery behind the new plan — just the realization that the complexity of the project required a more ambitious engineering solution. Between buried Con Edison transmission lines, 100-plus-year-old water mains and sewers in need of replacement, city engineers agreed that moving the physical flood wall under the park, and raising the entire park above it, would make the best flood barrier and also protect the park itself from flooding, as well as reduce long-term maintenance costs.

“As we delved into the design, and the understanding of the site conditions, I think we began to understand just how complex a site it is, and how complex a problem it is,” Alda Chan, the director of resiliency for the city parks department, said in a recent interview.

Gale Brewer, the Manhattan borough president and a presumptive incoming City Council member representing the Upper West Side, said she felt the issues were related to poor inter-agency communication — a charge city officials refuted.

“If agencies don't talk to each other in a meaningful way, it's hard to get answers,” she said. “This administration is particularly challenged in terms of agencies collaborating and communicating.”

Local resident leaders say that the community broadly has accepted the new plan, even though they say it took longer than it needed to because of how the city introduced it.

“The city did not seem prepared for the onslaught,” Avila-Goldman said. “The issue isn't one of the city being nefarious actors as there needing to be more transparency for the community to understand what's going on.”

Yet the activist movement has grown, papering lampposts in the park with posters criticizing city leaders over the plan and holding continued protests at City Hall featuring people chained to trees.

The activists also remain concerned that the new plan does not offer immediate flood protection, although the city has said it is planning to install the flood wall to protect against storm surges within a couple years.

“We have no assurance that this plan will at all protect us from an Ida-type event,” said Tommy Loeb, a member of East River Park action.

‘We can’t risk any more delays’

The East River Park project is regarded by city officials and resiliency experts as the first of its kind in the city, and possibly the country. That has made it something of a canary in the coal mine as New York City’s laborious, punishingly slow public development process confronts a climate that is changing more quickly than scientists expected.

“This is a project that's the first of its scale,” said Carlina Rivera, the City Council member whose district includes the park. ”We want future projects all over the city to learn from it and be even better and be even more efficient. We can't risk any more delays.”

One thing nearly everyone agrees the city failed on: communication.

“We get it,” said Jamie Torres-Springer, commissioner of the city’s Department of Design and Construction, which is overseeing the project. “We have said very clearly that we could have communicated better about the change in the engineering approach. We take full responsibility for it.”

But Torres-Springer pushed back against the idea that the city could have been more transparent in releasing internal planning reports community members were asking for. All the important information, he said, ends up in the environmental impact report, which is fully public.

“If the city released every internal memorandum before we make a decision, and present a preferred alternative, we would just cause massive confusion,” he said in a recent interview.

Brewer said that the city underestimated how heavily used the park is, and did not plan for alternatives for basic things like sports leagues, and appeared to slow-walk several compromises called for by residents. It took two years, she noted, for the city to tell the Lower East Side Ecology Center it could continue its composting operation at the reconstructed park, and to find funding to cover the stage of the park’s rebuilt amphitheater.

Pre-planning for major resiliency projects could eliminate this issue, according to Brewer, as well as give communities a more realistic idea of what complications ambitious resiliency projects might face.

“The vision for things sometimes doesn't meet the reality of the design of it,” said Rob Freudenberg, vice president of the Regional Plan Association’s environmental and energy programs. “This was a dramatic example of that. That you can chalk up to not having done adaptation projects before.”

Activists who oppose the plan have called for a second oversight hearing on the plan and a new environmental review, but there are no plans for a hearing. Justin Brannan, chair of the council’s committee on waterfronts and resiliency, and representatives for City Council Speaker Corey Johnson, did not respond to a request for comment.

Rivera said she would support an oversight hearing if a future issue with the construction plan made it necessary.

“City Council is taking its oversight responsibilities very seriously here,” Rivera said. “We’re just as frustrated that we thought it was getting underway in the spring and it's just getting started now.”

Or very nearly getting started: The city is still facing two appeals from lawsuits related to the park project, one from ERPA alleging that the city is illegally removing park space from public use, and another from the contracting firm whose bid was not selected for the East River Park work.

Torres-Springer said the city cannot comment on ongoing litigation, and insisted the city is planning to start “significant construction work” in the park this fall. The plan, he said, is still for the rebuilt park to open by the end of 2025.

“There's always risk that the courts or litigation will slow us down,” he said. “But we’re full speed ahead right now.”