New York City is entering a new era in the struggle to adapt to the threats of climate change.

Last September, Hurricane Ida — and the deadly flooding it caused — shocked the city even after a summer of intense rainfall, debilitating heat and smoke-filled air, renewing concerns over how unprepared the urban infrastructure is for the effects of climate change.

The controversial plan to rebuild East River Park as a flood barrier for the Lower East Side — the signature resiliency project of the administration of former Mayor Bill de Blasio — overcame two key legal challenges in the mayor’s last days in office in December, allowing construction to finally begin years after the plan was finalized.

Now, Mayor Eric Adams has taken office with a post-Ida resiliency plan already released. Two more plans will be released this year: a major report on adaptation from the city’s climate resiliency office, and a separate plan on resiliency projects for all five boroughs required by a recently passed law to be released by years’ end.

The city has a long laundry list of resiliency efforts that are at various stages of development, including several that Adams indicated he would “fast track” in his post-Ida plan. Some, like adapting neighborhoods around Jamaica Bay, have been in the works since before Hurricane Sandy, and others, like NYCHA’s resiliency needs, have yet to be fully priced out.

The city is facing a crucial period over the next few years, adaptation experts say, and needs to offer as many fully realized plans as possible to be competitive for billions of federal dollars flowing from the $1 trillion federal infrastructure bill passed in November.

“As climate effects get worse, we’re realizing how far behind we are in implementing these,” said Rob Freudenberg, vice president of environment for the Regional Plan Association. “In some cases we have good solutions for what can be done. So we have to make sure we get things done.”

The resiliency work of the next several years will need to happen with both major physical developments along shorelines and within neighborhoods, as well as in the nuts-and-bolts world of finding funding sources and creating new regulations, said Kate Boicourt, a director at the Environmental Defense Fund who focuses on the region’s coasts and watersheds.

The administration already faces a requirement from a law passed by the City Council in October to create a citywide resiliency plan this year, and can also expand guidelines for resilient development, she said.

“It's on the Adams administration to further develop those guidelines into a scorecard for resiliency,” along the lines of the current building emissions scores, Boicourt said. “It’s a technical, hard thing to do, and he needs to take that on.”

Here is an introduction to some of the resiliency efforts that will take center stage during the Adams administration.

Financial District and Seaport

Last month, the city released a finalized version of its plan to build out flood protection on the east side of the Financial District and along the historic Seaport. The area will see monthly tidal flooding within the next two decades without significant infrastructure changes.

The project will extend the shoreline from the Battery to the Brooklyn Bridge into the East River by about 90 feet, adding new piers and building out an esplanade in front of a permanent flood wall. Pedestrians will be able to enter the riverfront area and access ferry stations at gaps in the flood wall, which will have movable floodgates that close during storms. The design, however, is “flexible,” according to an official at the city’s Economic Development Corporation, which is overseeing the project, and subject to further input from community groups and regulators.

None of this will happen anytime soon. The full project will take at least 15 years to complete, and cost as much as $7 billion, according to the city’s plan, and requires state and federal permits to move forward and secure funding, because it involves building into the water.

Yet the city has said it will complete some interim flood protections for the Seaport area within five years with $110 million in funding recently committed by de Blasio.

Tibbetts Brook

A century ago, the city covered up a stream that ran from Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx out to the Harlem River out of concerns that its polluted waters were causing disease. But pushing the stream into an underground tunnel created another problem: During Ida, billions of gallons of rainwater that the stream would have normally fed into the river instead were pushed back above ground — and onto the Major Deegan.

Now, after decades of local activism, the city is pushing forward a $130 million plan to “daylight” the stream, bringing it back above ground and creating a mile-long green space running parallel to the Major Deegan. The city’s Department of Environmental Protection, which manages the sewer system, is currently working on a design for the project with the parks department and local community groups, according to Lauren Bale, a spokesperson for the mayor’s office.

Sen. Chuck Schumer has said that part of the funding will come from the infrastructure bill, but the project requires CSX, the railroad company, to sell or donate the land for the resurrected stream.

In an emailed statement, Sheriee Bowman, a spokesperson for CSX, wrote that the company “has had numerous conversations over the years with New York City regarding the potential sale of the Putnam Branch Corridor. We maintain our commitment to determining if a mutually beneficial transaction can be agreed upon.”

Hunts Point

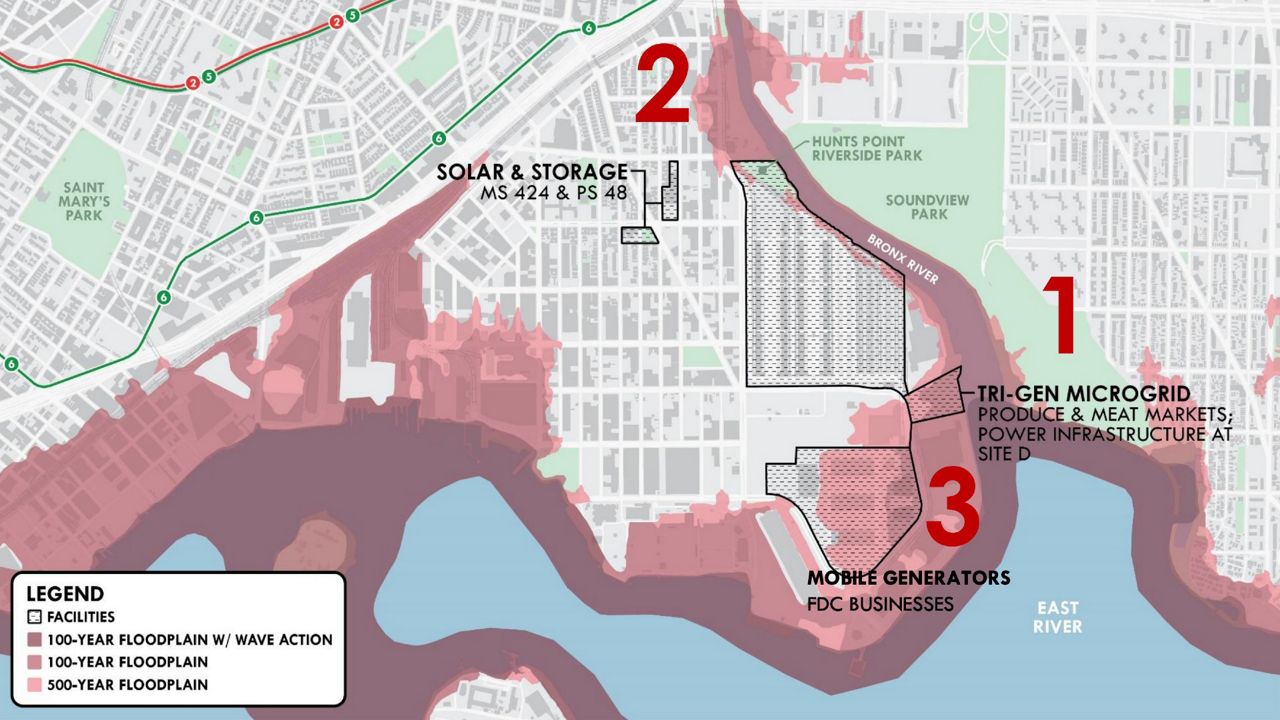

This peninsula in the Bronx is home to the Hunts Point Distribution Center, which supplies much of the city’s wholesale meat and 60% of its produce. In the wake of Hurricane Sandy, local community groups created a design proposal for coastal flood protection that won millions in federal dollars through the Rebuild By Design competition, which also awarded major funding to flood protection projects around Lower Manhattan.

The design, led by the urban design firm Olin, would have created a coastal greenway with flood protection similar to the new Financial District plan, on a much smaller scale.

In the years since, the Economic Development Corporation, which oversees the Hunts Point market, shifted the plan to focus on direct flood protection for some of the market’s buildings and creating solar powered hubs at two schools in the neighborhood, to make them safe havens during storms.

The EDC reasoned that the residential part of the neighborhood is out of the flood zone, and many of the market’s buildings are elevated out of the flood zone as well, since the floors are at the height necessary to load food onto semi-trucks.

But the change in the plan has brought some pushback from local groups and adaptation efforts, who have pushed for the original, more comprehensive plan to be reinstated.

“The city’s plans are not gonna protect our food supply,” said Amy Chester, the managing director of Rebuild by Design, the planning firm that spun out of the design competition.

Flushing Meadows Corona Park

Queens’ premier park and recreational area faces severe flooding risk in the coming decades, with much of the park projected to be covered with water during monthly high tides by the 2050s, according to maps created by the New York City Panel on Climate Change.

Yet although the park was included in Adams’ post-Ida list of resiliency plans his administration will “fast track,” no such plan currently exists for the park, according to adaptation experts. The city only recently finished a construction study, begun in 2017, to replace the Tidal Gate Bridge, built ahead of the 1939 World Fair, which keeps storm surges in the Flushing Creek from overflowing into the park grounds.

Indeed, during Hurricane Sandy the bridge saved the park from likely catastrophic flooding, with some human help: Two parks department workers realized that the power outage in the area meant the gates could not be closed electronically, and spent hour hand-cranking the gates shut in between tidal surges.

Local community groups, along with the Waterfront Alliance, are seeking $530,000 in federal funding to develop a resiliency plan for the park.

Karen Imas, the senior director of programs for the Waterfront Alliance, said the plan is crucial to preventing both coastal and inland flooding in northern Queens.

“There's been a gap in looking at everything from Flushing Bay to Flushing Creek, which then feeds into the lakes in Flushing Meadows Park,” Imas said.

In an emailed statement, Megan Moriarty, a spokesperson for the parks department, said that the city has invested more than $350 million “in recent and upcoming park renovations, including projects that increase resiliency and improve stormwater management.”

Brooklyn Greenway

Adams has already positioned himself as a bicycling mayor, riding a Citi Bike to work on his second day in office and promising to build hundreds of miles of protected bike lanes throughout the city.

In his post-Ida plan, Adams nods to the Brooklyn Greenway, a plan to create a continuous shoreline bike path around the borough, with protected paths connecting major parks. While the Greenway runs for long stretches, such as from Dyker Beach to the bottom of the Army Terminal, it has crucial gaps, including most of the bottom of the borough.

There are potentially many millions of federal dollars available for the Greenway, according to Terri Carta, executive director of the Brooklyn Greenway Initiative. She wants to see the Adams administration build out temporary bike lanes in areas that don’t have them, such as with jersey barriers, ahead of more permanent paths.

“We would like to see that done year one in Adams' administration,” she said. “We can't wait for the capital process. We need to have the roots established now.”

Resilient East Harlem

In 2018, the city created a major resiliency plan for East Harlem, which faces severe flooding risk according to present-day flood maps from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Yet that full, 280-page report has remained unpublished, with the city releasing only a summary of the report.

The city says it is moving forward on several elements of the plan. NYCHA and DEP have applied to FEMA for funding to reduce risk of extreme rainfall at the Clinton Houses. The city has plans to create a new waterfront park, comprising seven acres between 125th and 132nd streets, as well as invest hundreds of millions to make repairs to the East River Esplanade in East Harlem. The parks department is currently creating a project schedule for that work, Bale said.

Other elements of the resiliency plan, such as direct improvements to stormwater drainage, have not been started.

Jamaica Bay

Despite the substantial flood risks facing neighborhoods around Jamaica Bay — from Howard Beach to Breezy Point — there’s no baywide resiliency plan. Several neighborhoods have worked with design firms to create visions for coastal protections that also serve as green space, or have seen resiliency reports from the city, though not all have received city funding.

Some residents are hoping for a cure-all from the Army Corps of Engineers, who have resumed a regional coastal flood risk study that was shut down by the administration of former President Donald Trump. That study, which is expected in spring 2023, will likely propose a flood wall that could close off the mouth of the bay to storm surges, resiliency experts say, though a timeline and cost for that project are not clear. The city has pushed for a storm surge barrier to be built in the bay.

A resiliency plan for the Edgemere neighborhood of the Rockaways recently entered the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure process, heading for a vote in the City Council in June of this year, according to the Housing Preservation and Development department.

The plan would raise the shoreline and preserve some coastal areas as open space to guard against storm surges as well as elevate 107 homes.

But the project also adds housing to the area, which alongside other developments could bring thousands more residents to some of the most flood-prone parts of the city.

“We really want a coherent evacuation plan,” said Jonathan Gaska, the district manager of Community Board 14. “We don't think that exists.”

Gaska said that the community has asked for a comprehensive study of traffic given the added housing units, but hasn’t received a response from the city.

“You can't put three pounds of baloney in a one-pound bag,” he said. “But that's what they're doing here.”

NYCHA

The city’s public housing is facing massive backlogs of repairs and updates to aging buildings, which NYCHA has estimated at $40 billion to get into a state of good repair.

Yet that number does not include the authority’s needs in adapting to climate change, according to Joy Sinderbrand, NYCHA’s vice president for resiliency.

“These developments were built decades ago, when the level of rain we have right now is really unfathomable,” she said in an interview last month.

The authority is currently working through flooding protection projects across its developments, relying on $3.2 billion in federal funding — the largest single federal investment in public housing history, Sinderbrand said. The projects include replacing heating systems and making them floodproof, as well as creating flood walls around some particularly exposed buildings, such as on the Lower East Side.

“These projects are really the most significant investments that any of these developments have ever seen,” Sinderbrand said.

Yet stormwater flooding remains an issue across NYCHA buildings. Sinderbrand estimated it would cost $1.6 billion across all the developments just to replace the pipes that carry stormwater to the city sewer system.

She said that a good portion of her work is generating the data necessary to ask for funding for resiliency projects, since NYCHA’s funding is typically earmarked for specific purposes.

Sinderbrand’s office is about a third of the way through inventorying the authority’s trees, because while the developments’ green spaces often provide a cool refuge in otherwise overheated neighborhoods in the summer, the authority does not know what trees are on its property or what shape they’re in, she said.

“Inasmuch as we can create a state of good repair and adapt at the same time, that's the goal,” she said.