CINCINNATI — The Ohio River has played a major role in Cincinnati’s history, helping it blossom into a thriving capital of industry in the 19th century and once become the sixth-largest city in the United States.

In the early 1800s, Cincinnati developed into an important meatpacking center, earning it the nickname of “Porkopolis.” Businesses ranging from soapmakers to brewers also took advantage of the river as a major shipping corridor to the west.

The river’s proximity also created jobs, with numerous restaurants and taverns popping up to meet the needs of settlers traveling westward via steamboats.

But for tens of thousands of Black men and women, the Ohio River represented something more crucial than money: Freedom.

What You Need To Know

- The Ohio River served as a line of demarcation between the slave-owning southern states and the free states in the north

- It's estimated that 40% of escaped slaves who made it to freedom went across the Ohio River

- While Ohio was a free state, tensions were often high as not everyone was onboard agreed with freeing Black people

- Cincinnati was home to a variety of abolitionists, including Harriet Beecher Stowe who wrote "Uncle Tom's Cabin"

The Ohio River was a demarcation point between southern slave states and the so-called free states in the north.

Between roughly 1800 to 1865, fugitive slaves escaped captivity by crossing the Ohio River. Many found refuge in the Queen City, some staying there temporarily before heading to Canada.

The river served as the figurative and literal epicenter of the Underground Railroad, a network of secret routes and safe houses established across the U.S. People in search of freedom saw the Ohio River as their route to freedom and Cincinnati and Northern communities as a chance at hope and a new life.

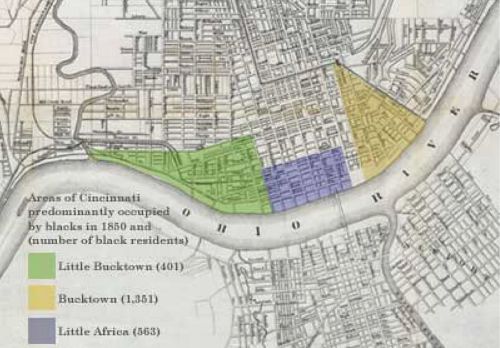

In 1850, Cincinnati had the third-largest African American population of any city in the nation.

Christopher Miller, an educator with the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in downtown Cincinnati, said the early Black communities were significant and resilient, especially along the riverfront.

“Those communities were very, very important when we learn about Underground Railroad history because when people would cross over the Ohio River heading North, it was these communities that provided safety, provided help for those freedom seekers,” said Miller, who has been with the Freedom Center since its opening in 2004.

The museum was designed by Walter Blackburn, an Indianapolis architect who was the grandson of slaves. He died in 2000, before the project was completed.

“The building was designed to represent the importance of the river and the struggle and the continued journey north to Canada,” Miller said. Pointing to the exterior walls, Miller said visitors will notice one side of the stone is smooth while the other side is rough: “The smooth side represents the triumphs and the rough side represents the struggle.”

The museum’s circular stairs and curved walls represent the river. The outside boulders and stone pathway represent the two border states – Ohio and Kentucky.

“Our building is divided into three pavilions,” Miller added. “Each pavilion represents a core value: Courage, Perseverance and Cooperation.”

Oprah Winfrey, Muhammad Ali and former First Lady Laura Bush helped break ground for the museum in 2002. More than 20,000 people attended the opening celebration two years later, Winfrey and Bush among them.

Every year, it’s nominated as one of the best museums in the nation. It remains one of the strongest museums centered around African American history.

Cincinnati’s early Black residents

The Freedom Center views itself as a “museum of conscience” – an education center first and foremost, but also a place for dialogue and “difficult conversations” about the nation’s history. A lot of that history took place on the Freedom Center’s front door.

The site where the Freedom Center exists today is in the heart of what was once called Little Africa, one of the early Black riverfront communities. Others were Bucktown and Little Bucktown. The Museum also within a stone’s throw of Northern Kentucky, where slavery remained legal until the passage of the 13th Amendment in 1865.

Prior to that time, freed slaves would be able to look across the river and see enslaved Black people taking part in day-to-day life, and vice versa.

One of the museum’s most powerful displays is the log structure that once served as a slave pen at a nearby Mason County, Kentucky, tobacco farm, less than an hour’s drive from Cincinnati. It was owned by Capt. John W. Anderson, who kept slaves in the pen until it was time for them to be sold.

Many of the original features of the pen remain, including seven of the original wrought-iron chain rings that shackled slaves still hanging from the ceiling. It also has a wooden panel inscribed with the names of Anderson’s 32 personal slaves.

“The slave pen authentically provides permanent and tangible proof to a story most people don’t want to talk about – the ugly truth of the internal slave trade,” said Carl Westmoreland, a senior historian at the Freedom Center.

Among the most prominent names associated the Underground Railroad is Harriet Tubman, a slave-turned-abolitionist who made more than a dozen missions to rescue approximately 70 enslaved people. But there were countless other people who helped, many of which lived in the Cincinnati region.

One estimate suggests that by 1850, 100,000 enslaved people had escaped via the network. Up to about 40% of fugitive slaves, or roughly 40,000 people, crossed the Ohio River to freedom on their ways to various part of the United States or Canada.

Playing off the railroad theme, resting spots along the Underground Railroad where the escapees could sleep and eat were given the code names "stations" and "depots", which were held by "station masters." "Stockholders" were the individuals who gave money or supplies to support the efforts.

Challenges for Black people still exist in the north

Before the Civil War, northern states that had prohibited slavery also enacted laws similar to the slave codes and the later Black Codes: Connecticut, Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and New York enacted laws to discourage free Blacks from residing in those states.

The Black Codes were oppressive laws curtailing the rights of African Americans.

Blacks were denied equal rights including the right to vote, the right to testify in court, and the right to equal treatment under the law. Most of the laws eventually were repealed around the same time that the war ended.

Cincinnati became significant during the era, Miller said, because it represented the turmoil over the “persecution and promise of the country.”

“Although Ohio was a free state, you still had oppressive laws like Black Codes, the Black Act of 1807, which restricted access and opportunities for people of African descent,” he added. “Just because Ohio was a free state doesn’t mean everyone in the city was a part of the anti-slavery movement. It had a mix of everything that was going on in the country at the time, the good and the bad.”

Miller described a “tension” in the community that led to a riot in 1829, caused partially due to competition between recent Irish settlers and free Blacks who were competing for the same jobs. And, of course, there were others who simply objected to the idea of Black people being free.

Riots in 1836 and 1841 “would get even more intense and more violent,” Miller said.

The riots affected the desire of some Black people to settle in Cincinnati and many decided to leave, he added. But the established communities of free people of African descent remained “strong and resilient” in part because of those who had not yet made it across the river.

“The amazing part of it is they remained strong and very purpose-driven. Many remained in these parts to help freedom seekers with their journey,” Miller said, adding that those communities remained “instrumental and very essential” to the efforts of the freedom seekers.

Salmon P. Chase, a former Supreme Court chief justice, was a prominent abolitionist living in Cincinnati. Chase was so outraged by the riots that he dedicated his professional life as an attorney working for the cause.

Beginning around 1830, Chase practiced law in Cincinnati, largely working on behalf of runaway slaves and white persons who had aided them.

The views on slavery weren’t solely dictated by north and south association. There were several notable abolitionists who lived in northern Kentucky, as well.

“The Free South,” an antislavery newspaper, was printed in Newport, Kentucky from 1858 to 1866 by William Shreve Bailey. In October 1859, a pro-slavery mob stormed his office and threw his printing presses and typewriters into the street.

Bailey’s friends, including the abolitionist Ira Root, of Newport, and several Covington residents, raised money to help him rebuild the newspaper.

The Black Brigade of Cincinnati

One of Miller’s favorite stories is about Cincinnati’s little-known Black Brigade.

Formed in 1862, the group of more than 700 Black men worked to construct barricades to defend Cincinnati from a feared Confederate attack.

The city’s mayor at the time, George Hatch, ordered police to forcibly round up Black men on Sept. 2, 1862 to take part. Approximately 400 men were abducted from their homes or workplaces, and then marched at bayonet point across the Ohio River into northern Kentucky to work as laborers, camp cooks, or servants. After public outcry and the intervention of a local judge, William Martin Dickson, the men were released and allowed to return to their homes.

Even though not required to take part, 718 African American men eventually volunteered for the service and worked alongside local soldiers to build critical fortifications on the other side of the river. One Brigade member, Joseph Johns, was killed in an accident during construction.

“You have finished the work assigned to you upon the fortifications for the defense of the city... you have labored cheerfully and effectively. Go to your homes with the consciousness of having performed your duty... and bearing with you the gratitude and respect of all honorable men,” Dickinson said, according to research by the Freedom Center.

On Sept. 9, 2012, nearly 150 years to the day of the defense of Cincinnati, a statue honoring the Black Brigade was formally dedicated at Smale Riverfront Park. The monument includes three life-size bronze figures, informational plaques, and the names of all known soldiers in the regiment. Also, there’s a poignant statue of a kneeling woman pointing out to the Ohio River and speaking to a small child at her side.

The monument's concept called for it to be built into the Earth, much like the original Black Brigade fortifications.

“Given even some of our more recent history, especially in terms of the relationships between African Americans and police and some of those things, it's just interesting to look back and see how some of those same issues arose in the past and how they were dealt with in a positive way,” said Erik Brown, a graphic designer who worked on the project.

Miller described the tale of the Black Brigade as nationally significant.

“This was the first military action by people by men of African descent, and this is before the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation,” he said. “These men were building fortifications to protect the city from Confederate forces who were on their way to seize the city of Cincinnati.”

As part of the commemoration, Miller and Westmoreland were part of a group of men who dressed in period costume, including carrying historic picks and shovels, and portrayed members of the Black Brigade. “We were proud to honor these men’s legacy,” he said.

History all around us

Ohio is home to numerous sites along the Underground Railroad, with many of them existing in and near Cincinnati. Among them is the Samuel and Sally Wilson House, the home of well-to-do merchants who used their College Hill property as a refuge for slaves until at least 1852.

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House in Cincinnati’s Walnut Hills neighborhood was once the home of the influential abolitionist who wrote the ground-breaking novel, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” Stowe lived at the Gilbert Avenue property until after she got married.

Stowe’s popular novel depicted the harsh conditions experienced by enslaved African Americans, the first time many White Americans were exposed to the brutality. For her book, Stowe interviewed several former slaves who had escaped to freedom along the Underground Railroad.

Another historic site is the home of abolitionist John Rankin in Ripley, Ohio, who lived about 50 miles east along the river. He was an active “conductor” in the Underground Railroad and many later abolitionists, including Stowe, were influenced by his antislavery writings.

There is a short film titled “Brothers of the Borderland” that tells the story of a female slave who managed to escape to freedom with the support from John P. Parker, a free black man in Ripley who helped fugitive slaves. The 25-minute film, narrated by Winfrey, is on display at the Freedom Center. The historic John P. Parker House still exists and is a Ripley attraction.

Learning lessons from the past

The Freedom Center focuses much of its work on using the Underground Railroad and the nation’s complicated history as a way to reflect on contemporary issues, such as human trafficking.

That includes the traditional type of slavery or forced labor, which still exists in parts of the world. But it also includes child labor, forced sex work and bonded labor, which means people are compelled to work in order to repay a debt and unable to leave until the debt is repaid. It is the most common form of enslavement in the world.

Understanding history, even the hard parts, is vital to creating a better future, Miller said.

“We want to challenge people to reimagine how they look at the Underground Railroad,” he added. Over the generations, it’s become “too romanticized” and people view it through a “very nostalgic lens.”

“The Underground Railroad was a movement truly based on life or death,” he said. “It was about changing laws and policies to improve and save lives.”

“One of the things that we want to make sure that people understand is that the social justice movements that are occurring now and occurred through the Civil Rights movement were built on the foundation of the Underground Railroad,” Miller said. “They're all connected to one another."

In 2014, the Freedom Center launched a new online resource in the fight against modern slavery, endslaverynow.org.

“Our goal is to make history real and relevant to those who walk through our doors or visit our website,” Miller said. “We want to make sure these important stories are heard so we can learn from them and grow as a society.”