This story is part of Spectrum News’ initiative, “Street Level,” which explores Ohio through the history and culture of specific streets and the people who live there. You can watch part two of Street Level: Vine Street here.

Vine Street has a history nearly as long as Cincinnati itself. The central thoroughfare, running through Over-the-Rhine and the Central Business District, has seen civil unrest, demographic shifts, exploding development and competing visions for its future. But through it all, there’s been one constant — a spirit of social justice.

It’s a spirit felt in marches for racial equality, in the hallways of a friary, at rallies for affordable housing and among the monuments of a museum commemorating the Underground Railroad.

Spoken word artist and musician Siri Imani is committed to keeping that ethos of service alive. She calls herself an “artivist” — an artist and an activist, and she weaves messages promoting self-love and racial and economic justice through her lyrics.

“The art of it kind of softens the speech, and it makes it a lot more digestible,” Imani explained. “If they don’t respect what you’re saying, they will at least respect the art of it and it’ll plant the seed.”

“She touches your spirit,” remarked Imani’s mother, Jennie Wright, a fellow artivist. “She’ll get you riled up and make you want to do something.”

Wright spent decades performing poetry herself under the stage name “Black Buddafly” before developing a lung disease. Imani grew up tagging along with her mother to shows, and credits Wright as her biggest inspiration. Growing up around her mother and her friends, Imani said, helped her find her own voice.

“People who are used to expressing themselves and encouraging that in me early, you know, kind of gave me just the freedom I needed to figure out who I wanted to be and really step into that,” Imani explained.

Imani also watched her mother’s dedication to serving others. Wright hosted open-mic nights and taught art classes to kids, helping younger generations learn to express themselves.

“It’s just how I was raised and how I wanted Siri to be raised,” Wright said. “If you see something, you do what you can do to fix the situation, to be of help.”

Imani took the lesson to heart. For years, she has used the proceeds from her performances to help feed people experiencing homelessness. It’s an effort that started with her and fellow activists driving hot soup around to people living on the street — and has evolved into a monthly potluck.

Potluck for the People takes place downtown, in Piatt Park — and it offers more than just food. Attendees can also get free clothing and medical care while gathering with others in a festive atmosphere.

“As things went on, we started realizing this shouldn’t just be like a ‘hi, bye’ situation. ‘Here’s your food. Never see you again.’ We started thinking of how we can create more of a block party feel versus a serving feel,” Imani said.

“When you’re homeless, it’s like people try not to see you,” Wright added. “So to go somewhere, to be seen, to joke around, to laugh or listen to music, you know, not just get your body fed, but to get your spirit fed too, I mean, that’s my favorite part about potluck.”

Commemorating freedom's heroes

Just a few blocks south of where the potluck takes place, there’s a monument to another social justice effort — and it’s one of Cincinnati’s earliest. The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center honors the network of people, Black and white, who offered shelter, food and aid to escaped enslaved people in the 1800s.

“The Underground Railroad is absolutely a social justice movement,” said Christopher Miller, the Senior Director of Education at the Freedom Center. “It’s an act of resistance towards systems that are set to oppress, devalue and degrade certain individuals.”

The Freedom Center stands on the banks of the Ohio River, overlooking former slave state Kentucky.

“This area was the gateway to freedom for hundreds and hundreds of people who crossed over the Ohio River,” Miller explained.

Once free, many Black people settled along Cincinnati’s riverfront in what was once called “Little Africa” — in the same area where the museum now stands.

Looking over the Freedom Center’s balcony, Miller mused, “This legacy that is steeped in courage, cooperation and perseverance and freedom is connected with the building right here.”

But the new Black settlers would face resistance. Racism and competition for jobs fueled white mobs, who attacked Cincinnati’s Black communities in a series of riots in the mid-1800s.

Miller said, “Some people may agree that you don’t deserve to be enslaved, but they also might turn around and say, ‘you don’t deserve to have equal access to what, the access that I have.’’’

In the wake of the riots, Cincinnati’s Black population declined as many fled the city. Around the same time, a few miles north, another group of newcomers was arriving in droves.

A wave of new settlers

“Over-the-Rhine owes its existence to German immigrants,” said Stephen Hampton, the executive director of Cincinnati’s Brewing Heritage Trail.

The neighborhood’s name was a nod to the Rhine River in the old country and Cincinnati’s former Miami and Erie Canal. Anyone coming from downtown had to cross over the canal to access the neighborhood.

“It was a joke that you were crossing the Rhine River into this little Germany,” said Hampton.

As Cincinnati grew, German immigrants made up a third of its booming population. But once again, new arrivals sparked tensions, and in 1855, anti-German sentiment reached a fever pitch between Germans and so-called “nativists.” The nativists supported an anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic candidate for mayor, whose attacks on immigrants caused rising tension on election day.

A mob of Nativists invaded Over-the-Rhine, but the Germans fought back — building a barricade across Vine Street and successfully defending their neighborhood.

But while the threat of violence passed, anti-immigrant sentiment lingered.

“German immigrants certainly faced a lot of pushback,” Hampton said. “They weren’t always allowed to be in the same company as those earlier folks who were here.”

An oasis in Over-the-Rhine

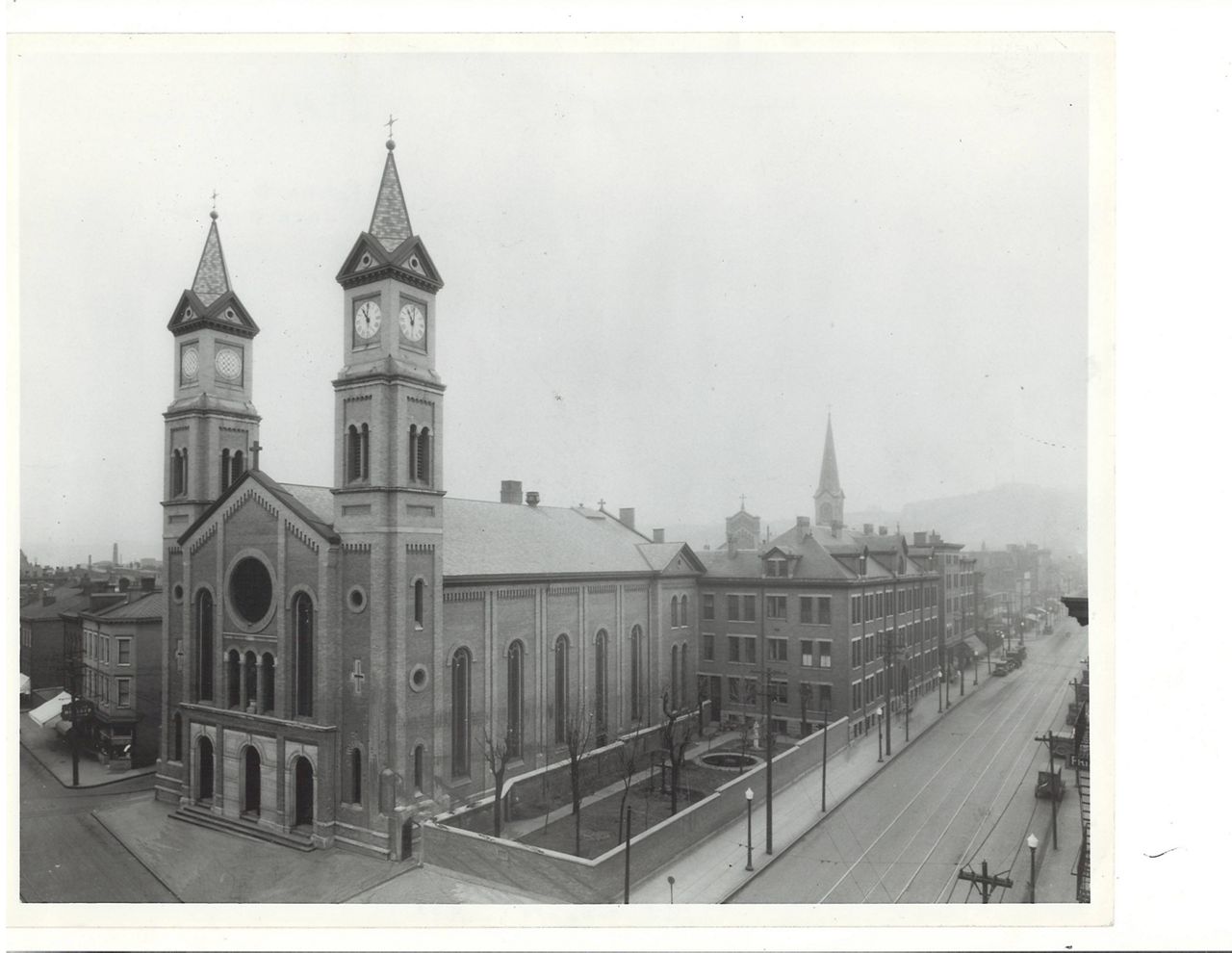

Within OTR, though, there was a group that provided refuge in Cincinnati’s burgeoning German community. In the mid-1800s, members of the Franciscan friars, a Catholic monastic order, made the journey from Austria to Over-the-Rhine.

“Our main mission is to be a brotherhood,” said Father Al Hirt, a friar, and the pastor of St. Francis Seraph Church. “We do focus on care for those who have seemed less cared for, who are on the margins, kind of left out.”

“When I think about those first Franciscans who came to Cincinnati to minister to the German-speaking people…we now stand on the shoulders of giants,” said Brother Tim Sucher, pastoral associate at St. Francis Seraph Church and guardian of the friary.

From their friary in OTR, the early friars planted seeds of social justice as they served the growing community — founding a school and church where they taught and ministered to OTR’s Germans in their native language while helping them acclimate to life in Cincinnati.

“They had to integrate themselves, helping people get integrated into life in America, but preserving all the German traditions,” said Hirt.

With those old-country customs came what would become a leading industry in Cincinnati.

“They brought their love of lager beer with them,” said Hampton. “And these hillsides in Cincinnati, deep underground, were a perfect place to build lagering cellars.”

The cellars acted as refrigerators for Over-the-Rhine’s many breweries.

“They would basically make this lager beer in the cooler parts of the year, store it in these massive cellars, and then sell it all summer long,” Hampton explained.

The German lagers fueled the economy, as well as a vibrant social scene.

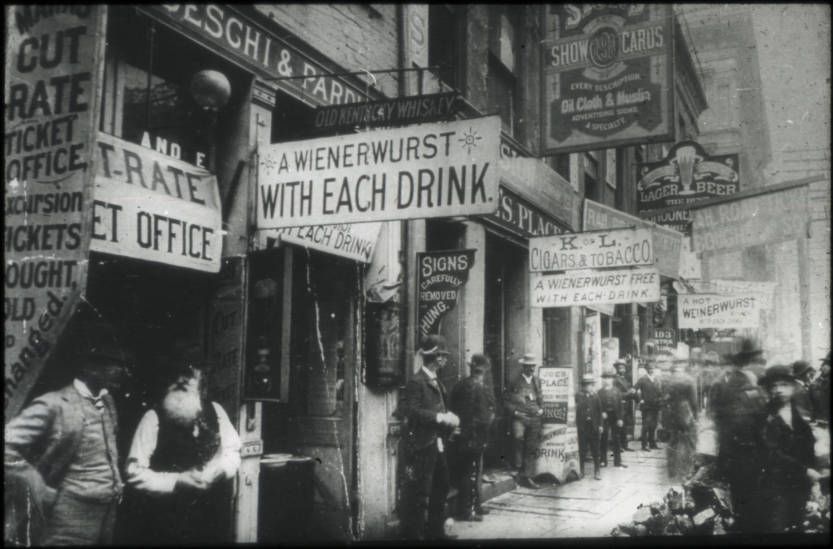

“Vine Street was really the heart of Over the Rhine,” said Hampton. “That’s where there were literally dozens and dozens of saloons.”

But the street went quiet in the early 20th century, as Prohibition decimated OTR’s brewing industry. Meanwhile, World War I sparked anti-German hysteria, leading the city to strip away markers of German influence — changing street names and dropping language classes.

"All of a sudden, both their heritage, their German heritage was made illegal, and the way they enjoy themselves was made illegal,” said Hampton. “That one-two punch took a very long time to recover from.”

Over-the-Rhine’s Germans started leaving for the suburbs, leaving behind their ornate brick buildings and the skeletons of the once thriving brewing industry.

But on the corner of Liberty and Vine, the friars remained.

“With each change of seasons, the friars stayed and ministered to those whoever was here,” said Father Al Hirt. “[The school] is such a good anchor for the neighborhood because it’s so good that the kids have a place to go to school in a disciplined atmosphere, a safe atmosphere where people love them and care for them.”

Over the years, they’ve added new missions, like a soup kitchen, a bagged lunch program, and the Mary Magdalene House, a hospitality center offering showers and clean clothes.

“Needs change, but the needs have still been just as great over the decades that we’ve been here,” said Brother Tim Sucher.

As those needs changed, so did the faces of those who stepped through their doors. Starting around the 1940s, large groups of Appalachian people moved to OTR from Kentucky, looking for work in the city.

“There was a flood then of Appalachian people who were coming from Kentucky to find jobs in the city, and then, within another decade or two, the African-American population became much more dominant in Over-the-Rhine,” said Hirt.

African-Americans migrated from the South — and from just across town. Many Black families moved neighborhoods after Interstate 75 cut through the West End in the late 1957s, destroying homes and displacing residents.

The new groups were largely poor and working class, and OTR saw economic decline as low-income housing became concentrated in the neighborhood.

A new movement emerges

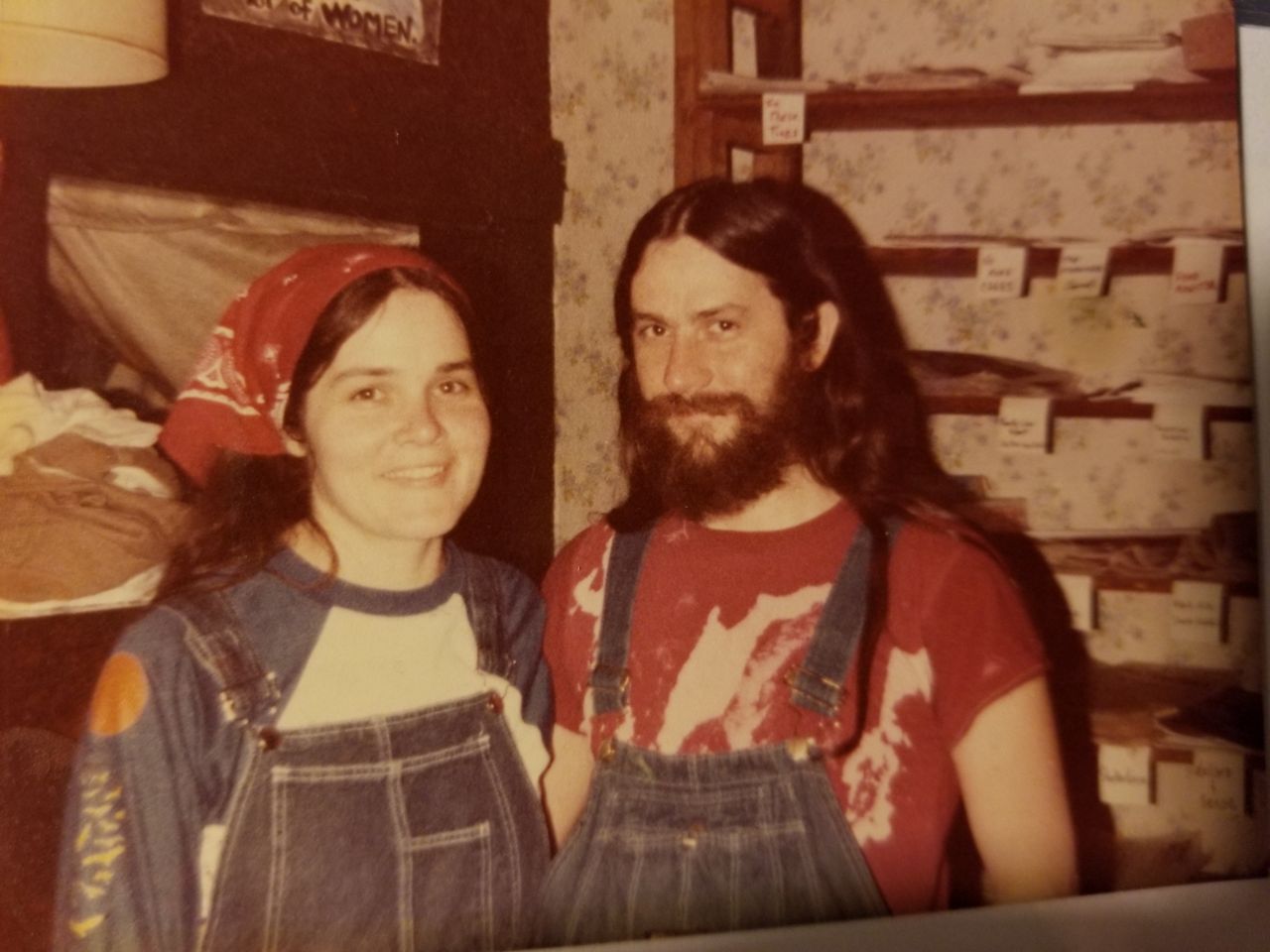

Amid increasing homelessness and crime, a new social movement came into the neighborhood. Bonnie Neumeier helped lead the charge, co-founding a coalition of organizations called Over-the-Rhine People’s Movement in 1970.

“Our movement was saying what we have in common is that we’re all at the bottom of the economic ladder,” Neumeier said. “Let’s join forces and try to, you know, make change.”

Early on, the movement founded a homeless shelter called the Drop Inn Center, advocated for affordable housing and fought displacement.

“If you’re going to be able to be here, you’ve got to be able to get some kind of community control of housing,” Neumeier explained.

Working alongside Neumeier was a charismatic but polarizing figure — a long-haired, bearded Vietnam War resister named Buddy Gray.

“Buddy was a fierce fighter for the people,” Neumeier said. “You knew where he stood and he was for the oppressed in the marginalized, and he would give his shirt off his back.”

Gray led an effort to buy up buildings in the community, hoping to turn them into affordable housing and prevent gentrification. When many of the buildings sat empty, the move drew sharp criticism from city officials and developers claiming he and the People’s Movement stood in the way of progress.

“They said that we were warehousing buildings to keep people with more resources out. And that was never our intent,” countered Neumeier. “We boarded them up until we were able to get money enough so that we could develop them.”

The People’s Movement also fought efforts to add Over-the-Rhine to the National Register of Historic Places, fearing the designation would lead to rising rents.

“People were upset with this. But what we were saying is that the faces of our people are more important than facades of buildings,” Neumeier said.

When asked why she thought the People’s Movement is controversial to some, Neumeier said, “Because we stand up to power and because we challenge the status quo.”

In 1996, a piece of the movement died when Buddy Gray was shot and killed by a mentally ill homeless man at the Drop Inn Center. Now, his mission for affordable housing lives on at Buddy’s Place on Vine Street.

“I think it’s a testament. It’s a legacy that we are still organizing and doing that work because we all believed in it. It wasn’t a one man show,” said Neumeier.

But as the People’s Movement holds onto Gray’s legacy, the surrounding scenery is changing. Luxury buildings and trendy cafes now dot many of OTR’s streets.

Those new surroundings also serve as reminders of their somber foundation. In part 2, we look at how a police shooting and the ensuing civil unrest would change Over-the-Rhine and Cincinnati forever.