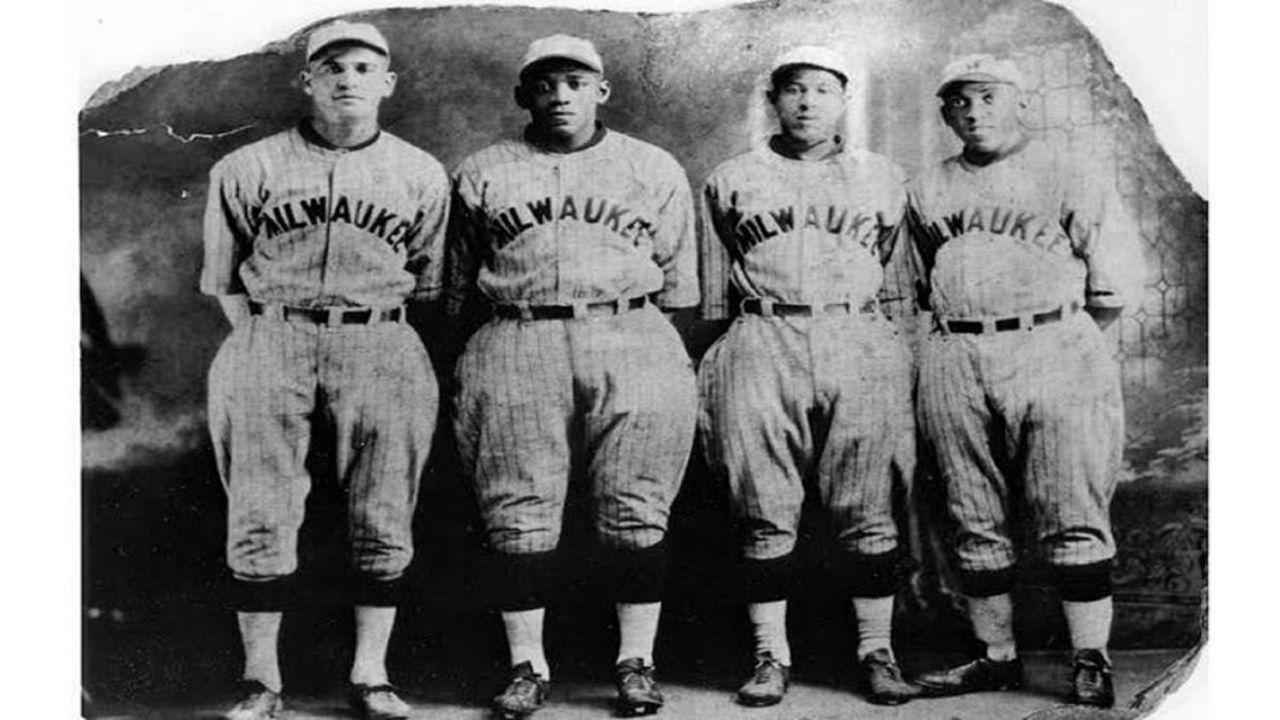

Most of us know this about the Milwaukee Bears: they were a baseball team that was once part of the Negro Leagues and celebrated by the Milwaukee Brewers once every season.

And that about covers it.

What You Need To Know

- The Milwaukee Bears, Milwaukee's only Negro League franchise, played just one season in 1923

- Beset by bad weather and poor attendance, the team moved to Toledo, Ohio in July of 1923 but still played the remainder of the season as the Milwaukee Bears

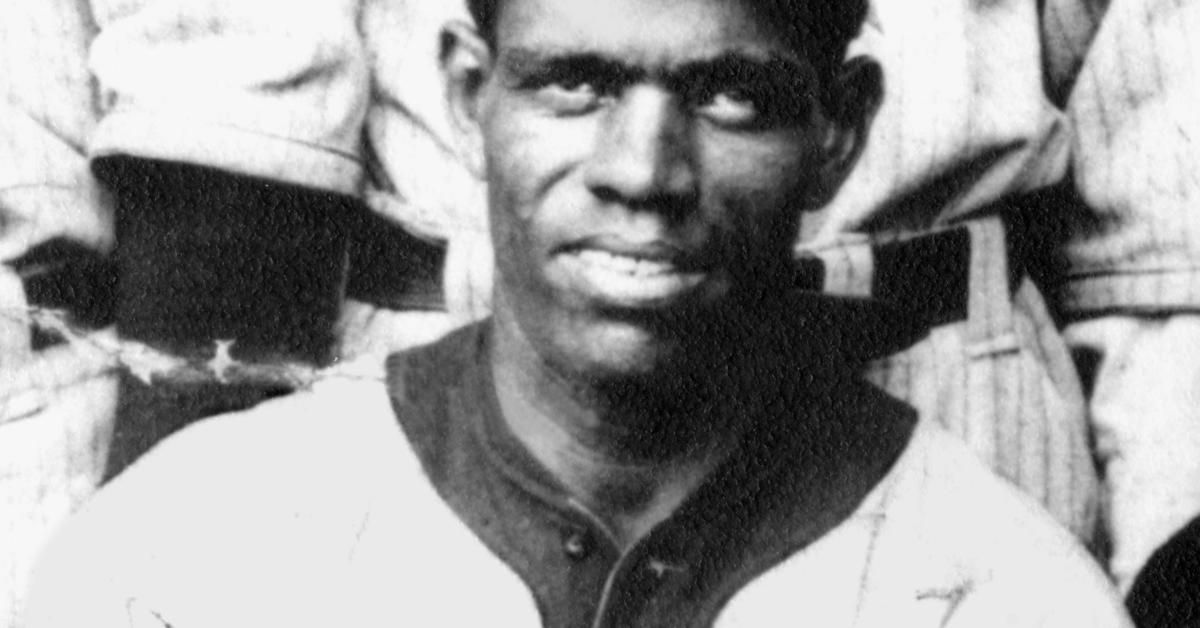

- The Bears' player/manager, Pete Hill, was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006. But his HOF plaque fails to mention his time in Milwaukee

- The Bears were one of the first Negro League teams to play a game umpired by Black men

But there’s a reason for that. The Bears’ stay in Milwaukee lasted about as long as an ice cream cone on a warm summer day. Largely ignored by the local press, and the fans, they packed up and left town after three months. And because of that, their place in history has been a mystery.

Baseball historians and the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum knew little to nothing about the Bears, other than acknowledging they existed.

Even the Baseball Hall of Fame — which inducted Pete Hill, the Bears’ one and only manager, in 2006 — fails to mention Hill was a player-manager for the Bears on his Hall of Fame plaque, though his plaque mentions the two other teams where he fulfilled that same role, the Detroit Stars and Baltimore Black Sox.

But thanks to one assiduous UW-Milwaukee doctoral student who doubles as a baseball nut, the Bears’ past is no longer a secret.

“It’s both challenging and liberating to be the first to write about something,’’ said Ken Bartelt, whose Master’s thesis is titled: Brew City Black Ball: Milwaukee as Microcosm of the Early-Twentieth Century Black Baseball Experience.

Bartelt combed through over 400 black and white newspapers from the 1920s, and various other sources, to piece together the story of the Bears, which also represented the story of America in the Jim Crow Era.

“You know, part of it is, I’m teaching you about baseball, which is really fun,’’ said Bartelt, who is pursuing his Ph.D. in history. “We all love baseball, right? It’s such a big part of our history of the country and in Milwaukee.”

“But we’re also talking about what I call real history, right? Talking about issues of race in America. We’re just doing it in a way where maybe you don’t realize, like, what we’re really talking about. We’re talking about baseball, but we’re talking about other things, too, that are important. And I like using baseball to do that.”

****

The Bears’ journey to Milwaukee began in Calgary, Canada.

Back then they were called the Calgary Black Sox, Bartelt said, and run by some friends of future baseball Hall of Famer Rube Foster, known as the “father of Black baseball.” Foster ran the Chicago American Giants and Bartelt deduced Foster wanted a team that was close to play and become part of the Negro National League.

They came to Milwaukee in 1922 and set up barnstorming operations, first as the Cream City Giants and then as the McCoy-Nolan Giants, and enjoyed their share of success. They traveled around the state, won far more than they lost, and drew nice crowds. But there were a couple of reasons for that.

“The thing about these barnstorming teams, they played anybody and everybody,’’ said Bartelt.

So playing against factory teams, town teams or newspaper teams was as much a part of the schedule as, say, semi-pro teams.

Their success at the gate wasn’t because they were putting together a nice string of victories.

“Traveling teams, a lot of the money they made was, like, kind of marketing the novelty of Blackness,’’ said Bartelt. “Like you go to these small, white towns in the Midwest, and way out West where there wasn’t much of a Black population, and that would be a way for the townspeople to kind of see Black people in real life.’’

After just one season, Foster had seen enough to believe Milwaukee could be a successful Negro League franchise. So in 1923, after the Cleveland and Pittsburgh franchises dropped out after the 1922 season, he created the Bears as part of the eight-team Negro National League.

But the 1923 season was not kind to the Bears. Bartelt said poor play and poor attendance led to financial struggles, which led the Bears to pack their bags for Toledo, Ohio, in July because the team there had disbanded. And despite settling in a new city, Bartelt said they would finish the season playing as the Milwaukee Bears.

****

So why didn’t the Bears succeed in Milwaukee? Pull up a chair.

For starters, they got off to a horrible start. Their season started in April and, according to Bartelt, April 1923, was very similar to April 2022. The weather stunk.

“So they had a hard time getting games in consistently and had a hard time practicing in Milwaukee, just because the weather was so crappy,’’ he said. “And it didn’t help that, like, nobody wants to watch a losing team.’’

When the Bears played, their success rate was worse than the ’62 Mets.

But there were other issues that led to their demise beyond their control.

First, they played at Borchert Field — which is now home to I-43 — a facility owned by the Milwaukee Brewers, a minor league team of the old American Association.

“So historians kind of call that the Achilles’ heel of Black professional baseball,’’ said Bartelt. “Throughout the history of segregated professional baseball, hardly any team owners owned their own places. They had a really hard time because of the inequalities of producing, like, generational wealth and access to buying city land and things. It was hard for them to own their own places, so usually, they rented from white team owners, or booking agents, that operated with different venues.

“So in Milwaukee, that was the case. They had to essentially get permission to use Borchert Field to book their games. But the (Milwaukee Brewers) would always take precedent. So if there was a (Bears) rainout, they would make sure that the white, American Association, Milwaukee Brewers game got played first.’’

Borchert Field did not have lights, so if the weather postponed a game and there was a scheduling conflict with the Brewers with the makeup date, the Bears lost a game.

Negro League teams also relied on the local Black population to support them. But Milwaukee’s Black population in the early 1920s was around 2,200 and, according to Bartelt, most were from low-income families. They had neither the money nor the leisure time, as the Bears played their games while many were at work.

“These people who were migrating from the South were only a couple of generations removed from slavery,’’ said Bartelt. “So they didn’t make a lot of money.”

So with limited money coming in, Negro League teams — which operated almost as independent contractors — would do what was necessary to stay afloat.

“The Black leagues, they needed to make as much money as possible,’’ said Bartelt. “So if somebody offered you money to play a barnstorming game against a non-Negro League opponent, you might be willing to take up that offer and cancel the scheduled league game because it’s promising more money. And that would happen.’’

The fallout from that development was a credibility issue.

“So one of the big problems with the Negro Leagues, the early years especially, was the scheduling imbalances created a kind of inequality in terms of games played and it made people question the validity of the pennant race,’’ said Bartelt. “Because how could you crown a champion when they played this many games, and the other team played maybe half that many games? How do you know who’s better?’’

In 1923, Bartelt said all eight teams in the National Negro League played a different number of games. And for the Bears, it wasn’t pretty. According to baseballreference.com, they finished that season with an 11-42 record in the NNL and an overall record of 14-47-1. They played just nine home games.

****

On the surface, the Bears weren’t much of a story. And their struggles on the field made them easy for the local press and residents to ignore. But like a lot of things, you have to peek below.

A future Hall of Famer managed them in Hill. Milwaukee was the home to Dave Wyatt, one of the most important black sportswriters in American history, who not only wrote the constitution for the NNL, but was the booking agent for the Bears.

But most important, the Bears were one of the first Negro League teams to play a game umpired by Black men.

Most of the umpires hired were white, for which Foster took a lot of heat in the Black press, Bartelt said.

“It was, ‘Hey, these are jobs that should be going to Black men, former Black ballplayers. That money could be kept in the Black community. Why are you doing this?’’’ Bartelt said of the criticism. “And also, optically, it sent a bad message, like, ‘Alright, we have white people who are kind of telling these Black guys what to do and that didn’t look good.’ So finally in 1923, Foster caved to the pressure and hired some Black umpires right here at Borchert Field in the first-ever game umpired by Black men. It was the Bears’ home opener.

“Jobs were hugely significant. Having a job was a big deal, so the more jobs that Black baseball could give to Black people really helped its status, like a race institution. Many people in the Black press really wanted Black baseball to do more to uplift the Black community. To employee people in positions like umpires.’’

The end of the Bears was not the end of Black baseball in Milwaukee, Bartelt said. The McCoy-Nolan Giants came back under new ownership and were successful touring the country for the next eight years.

“And it’s in 1932 that they fall off the face of the earth,’’ he said. “You can’t find any reporting on them anywhere. And I attribute that to the Great Depression. Most of these independent Black teams kind of went under during the depression; a lot of white independent teams went under as well.’’

****

The history of the Bears may still be unknown today if not for a class Bartelt took at UW-Milwaukee called “Baseball in American History.”

“A lot of the kids would sign up for a baseball class,’’ said professor emeritus Neal Pease. “You’d never get them to sign up for a course on African-American history, or labor history or American culture. But if you dress them up in a baseball class, then you can get them for at least an hour and introduce them into some of the, if I can say, more important things that historians deal with, and at least they get a taste of it.’’

So because of an innovative college class taught by Pease and industrious student like Bartelt, we all get to enjoy a taste of it.

“To be the person to bring this story and talk about these teams and the importance of Black baseball in Milwaukee kind of bring it to light is rewarding,’’ said Bartelt.

“I will say this, if there’s like a shortcoming of my thesis, or somewhere I would like to go in the future with, it is to find out more about these men,’’ he said. “You know, like, ‘Who are these guys?’ I don’t think that comes across in my thesis largely because those sources aren’t there, or at least I didn’t have access to them. They kind of just come across as names in a lineup or scorecard.

“But who was Pete Hill as a person? That would be nice to know. And so I think, whether it’s myself doing it in the future when I have more time to return to this, or another scholar, that would be great to find out more about that; the human side of this.’’

Story idea? You can reach Mike Woods at 920-246-6321 or at: michael.t.woods1@charter.com.