LEXINGTON, Ky. — In October 2017, the city of Lexington decided to permanently remove Civil War statues of two Confederate generals in its historic downtown, moving them to the Lexington Cemetery.

What You Need To Know

- Lexington more progressive than most cities in the south

- Project coordinator says Heritage Guide sets example for others to follow

- Eleven signs depict important people and places that shaped equality

- Video tour with audio available online

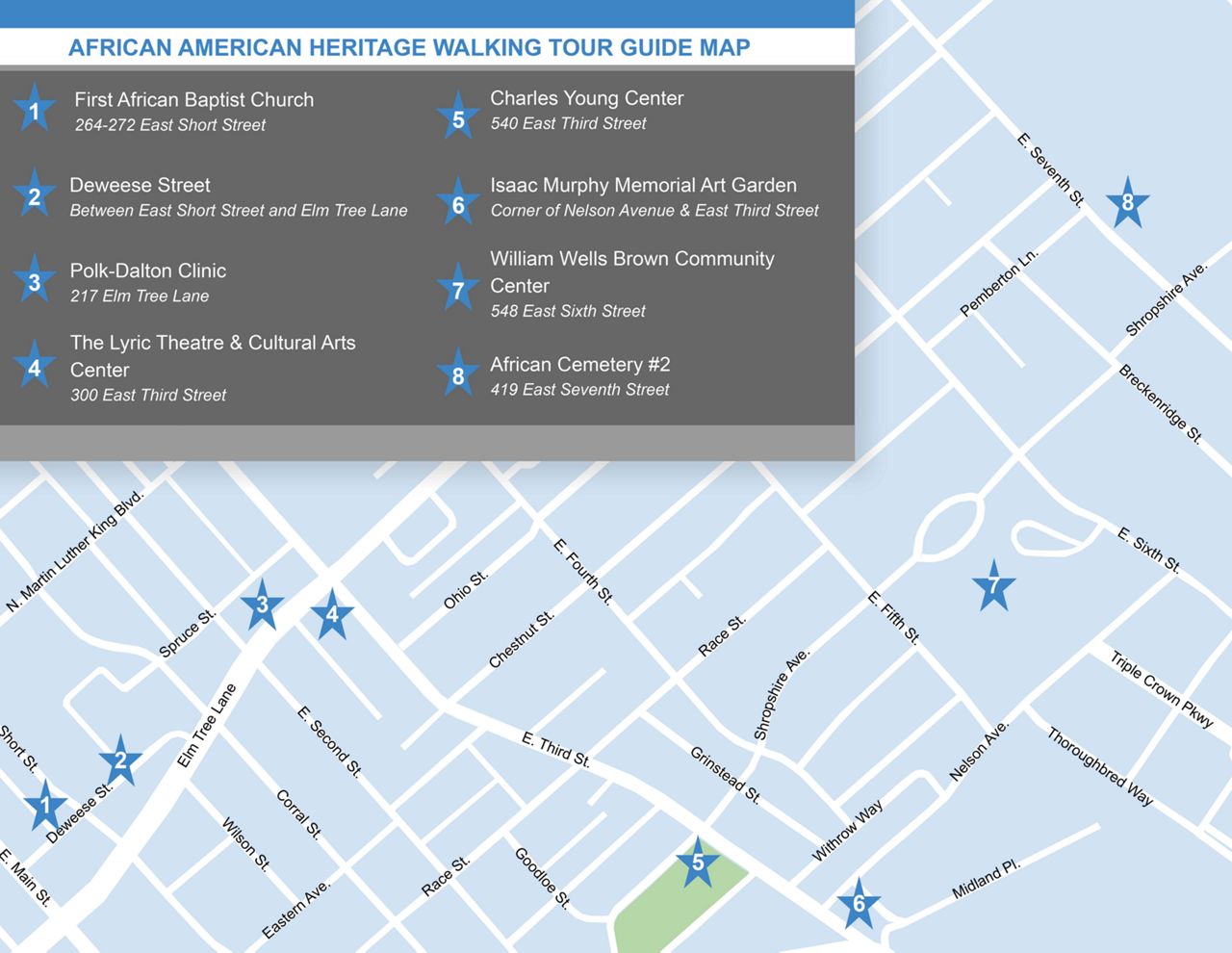

Over the years, Lexington has become known for its culture besides bourbon, horses and basketball. The African-American Heritage Guide in downtown Lexington was established to tell the cultural story.

There are 11 signs in downtown Lexington depicting the people and places that helped with the advancement of equality in Lexington. The signs include historical photos and stories about the city’s past.

“Throughout its history, Lexington has often been more progressive than its southern neighbors, setting an example for others to follow,” said Doris Wilkinson, a retired sociologist at the University of Kentucky who worked on the project. “We hope people explore the African-American Heritage Interpretive Sign Program to learn about the people, places and events that played a significant role in the advancement of equality, shaping Lexington into the city it is today. Looking back on that history, it’s important to recognize every part of Lexington’s past — the good, the bad and the ugly — so that we can celebrate just how far we have come.”

Wilkinson, 85, is the first Black person to graduate from the University of Kentucky in 1958. At the University of Kentucky, she was the director for the African-American Heritage in the Department of Sociology. In 1969, she became the first African-American woman to become a full-time faculty member at the University of Kentucky when she joined the Department of Sociology.

“The African-American Heritage Guide symbolizes a historic passageway from the site of a 19th-century slave auction block at ‘cheapside’ to freedom represented by the Urban League headquarters at 148 Deweese St.,” Wilkinson said. “Along the route, African-Americans contributed immensely to the rich cultural heritage of the city. Many of their architectural landmarks and historic properties, including cemeteries, may be found throughout the city and in the once rural hamlets of Fayette County.”

An online video tour with audio is available on the Lexington Public Library website.

Lexington African-American Heritage Guide sign locations

400 W. Main St.

Robert Charles O’Hara Benjamin was a vocal critic of racial violence and voter intimidation. Born in 1855, he practiced law throughout the U.S. and was the first African-American admitted to the California Bar Association. He settled in Lexington in 1897 and vigorously challenged Jim Crow practices in his writings, legal cases and activities of daily life.

275 S. Limestone St.

In the mid-1800s, Lexington’s free Black community was filled with driven individuals who purchased their own freedom and went on to either free or purchase their enslaved family members. As this community grew, they were not residentially segregated — freed blacks lived alongside white households throughout the city. South Hill was as important a neighborhood for Lexington’s white elite as it was for prominent members of the freed Black community.

250 W. Main St.

Before the famous Greensboro sit-ins, Lexington staged its own, starting in July 1959. Members of the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) protested businesses that practiced discrimination, and working-class lunch counters downtown were among those targeted. Demonstrating peacefully, they worked to fill segregated lunch counters, sitting in vacant seats meant for whites only.

100 E. Main St.

The Phoenix Hotel, which is now Park Plaza Square, is where peaceful sit-ins took place by Black women who led the fight for racial equality in Lexington’s Black Freedom Struggle. They sat day after day in the Phoenix Hotel’s restaurant, waiting for someone to acknowledge their patronage. Despite the lack of news coverage by the Lexington Herald and the Lexington Leader, the hotel quietly changed its policy and eventually served the civil resisters.

150 N. Limestone St.

Jordan Carlisle Jackson Jr. and Eliza “Belle” Mitchell Jackson became prominent community leaders, dedicating their lives to movements and organizations that offered Lexington’s African-Americans greater opportunities in education, political involvement and economic empowerment.

266 E. Short St.

Lexington’s First African Baptist Church was the first Black church west of the Allegheny Mountains. Established around 1790 by Peter Durrett, “Old Captain,” church congregations split over the decades to create both the Main Street Baptist Church and the Historic Pleasant Green Baptist Church. Between 1850 and 1854, First African Baptist was Kentucky’s largest congregation, Black or white, with about 2,000 worshipers.

102 W. Short St.

Over the centuries, Lexington has been a political, social and economic reflection of the Bluegrass State. Ties to slavery have been no exception. As an early metropolitan center, Lexington was a trading hub for all forms of exports, including human beings. Motivated by financial gains, bands of men formed slave patrols that captured runaway slaves and re-enslaved free African-Americans who had the misfortune of crossing their paths.

154 Church St.

This sign is at the site of the first free school for African-Americans in Lexington, named the Howard School. African-Americans in Lexington believed strongly in education, establishing private schools before the Civil War. By 1899, taxes supported three public schools for African-Americans.

175 N. Mill St.

As slaves of Henry Clay, Charlotte Dupuy and her family moved to Washington, D.C., with Clay during his time as Secretary of State. After Clay’s tenure, the Dupuy’s were forced to move back to Kentucky, sealing their fates as slaves. In February 1829, Dupuy petitioned the U.S. Circuit Court in Washington, D.C., to sue the Clays for her freedom and that of her children. Eleven years after the start of her journey towards emancipation, she and her daughter Mary Anne were granted their freedom.

535 W. Second St.

Alfred Francis Russell lived with his mother, Milly Crawford, in Glendower where they were enslaved. With a legal maneuver and a court case with the Todd family (including Abraham Lincoln), Polly Todd Russell Wickliffe emancipated Milly and 14-year-old Alfred in 1833. Through Wickliffe’s donations to the American Colonization Society, Milly and Alfred eventually sailed to the west coast of Africa. Alfred was elected vice president of Liberia in 1881 and then served as president from 1883 to 1884.

545 N. Limestone St.

Mary Ellen Britton was born in Lexington as a free person of color. She taught throughout central Kentucky, coming back to Lexington in 1876. Britton received her medical degree in 1903 and became the first licensed woman to practice medicine in Lexington. She built a home on N. Limestone Street in 1903, and it housed her medical practice until 1923. She continued to advocate for women’s rights until her death.