A newly adopted rule seeks to guide Maine’s efforts to reach its ambitious climate change goals, but environmental groups say the state will need even more specifics to make real progress.

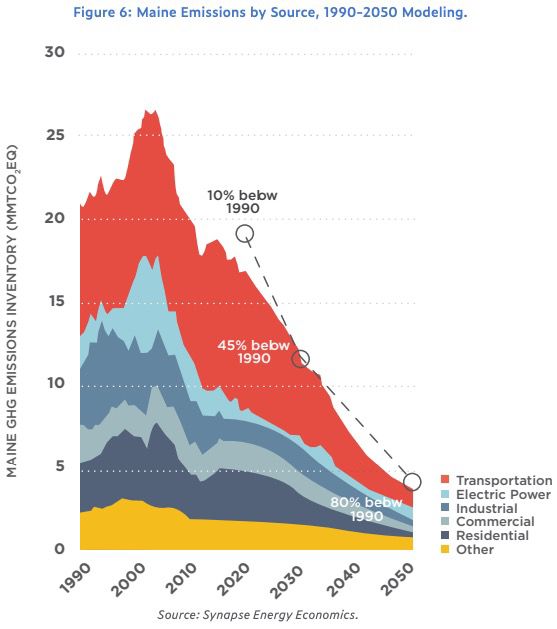

The Board of Environmental Protection approved the rule Thursday. It translates Maine’s greenhouse gas baseline of 1990 and its reduction targets of 45% by 2030 and 80% by 2050 into actual volumes of emissions, shedding new light on the challenges ahead.

The goals are the centerpiece of Maine’s plan to become carbon neutral by 2045, in time to try and avert the most catastrophic potential future of deadly heat, storms and rising seas.

Putting Maine’s goals into real-world terms

The new BEP rules say the state’s annual emissions in 1990 were about 32 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalents, which is a way to even out the relative warming impacts of different greenhouse gases. The rules say this means that in 2030, the state’s annual emissions should be 14.4 million metric tons lower than that, and another 11.2 million lower in 2050.

Put another way: the state climate action plan says Maine put out 17.5 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions in 2017. Under its climate goals, the state would be emitting 11.7 million metric tons in 2030, and just 3.7 million metric tons in 2050.

But what do those numbers really mean? An Environmental Protection Agency calculator puts them in real-world terms, showing the steep climb Maine must make to reach its goals and the many potential pathways to doing so.

This data shows that by 2030 — when a child born this year is in third or fourth grade — Maine must cut back the equivalent annual emissions of 3.1 million gas-powered cars, or about three and a half coal-fired power plants, or 613 million bags of trash decomposing in a landfill.

Maine could, in theory, reach its 2030 goal solely by converting more than half a billion incandescent lamps to LED lightbulbs, or by planting 238 million tree seedlings this year and growing them for a decade. Or it could run 3,000 wind turbines full-steam for a year — right now, Maine has 383 land-based turbines and hopes to build more offshore in the coming years.

The state has less than a decade to eliminate the emissions of roughly 33 million barrels of oil — about 1,000 times what the Wyman power plant in Yarmouth burned in 2020, according to federal data. And by 2050, Maine must avert the emissions of 26 million additional barrels of oil.

The ‘essence’ of the state climate plan

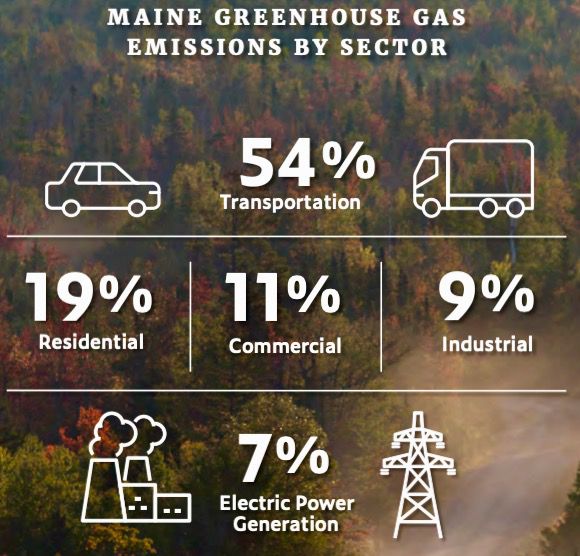

The state’s top emissions sources — transportation and buildings — are more diffuse and entrenched than a single power plant. It means success will likely require a range of complementary strategies, which are laid out in broad terms in the state’s climate action plan.

The plan’s implementation chart includes some specific goals — deadlines to deploy certain numbers of heat pumps, electric vehicles or levels of broadband access to reduce commuting. Other goals are less specific, with benchmarks such as “enhance” or “significantly increase.”

The plan does not include specific amounts of greenhouse gases from individual sources that the state aims to reduce. But the BEP says it will use its new general target numbers to help agencies build out detailed strategies in cost-effective ways, and to measure progress.

Tony Ronzio, the deputy director of Gov. Janet Mills’ Office of Policy Innovation and the Future, said this is “the essence of the climate plan.”

“Strategies to electrify transportation and reduce the need for driving, and making homes and commercial buildings more energy efficient and less reliant on heating oil through transition to high efficiency heat pumps are central to reducing emissions,” Ronzio said. “Creating more local renewable energy is also key, both for the climate effects, but also for the jobs and economic growth that comes along with it.”

These types of priorities have already led to some areas of progress. Ronzio noted the state has pushed out tens of thousands of heat pumps since 2019, working toward a goal of 100,000 by 2025 to offset the use of home heating oil. Maine relies on heating oil more than any other state.

Advocates call for more specific targets

Climate advocates say the state must do more to ensure it’s choosing the most efficient pathways to success. In comments to the BEP on its new rules, the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) and other nonprofits recommended that Maine break down the emissions goals into sub-targets for, say, transportation.

“Then you could start figuring out what policies you need to reach those goals, regarding electrification of transportation and the amount of funding, et cetera,” CLF attorney Nick Krakoff said. “(If) you just focus on the aggregate number, without looking at those sectors individually, it makes it sort of hard to figure out what policies you need.”

The BEP chose not to follow the groups’ recommendation. Regulators said in a response to public comments that not all sources of emissions fall neatly into one category and other state programs will track emissions in that way.

The climate action plan includes a “potential pathway” to the 2030 and 2050 goals that breaks down projected emissions reductions by sector, but those numbers don’t translate directly to the new BEP rules. The state also puts out an inventory of emissions by source every two years.

Krakoff expects the next inventory report, due in early 2022, to use the same accounting methods as the BEP’s new goal numbers. They include, for the first time, “biogenic” emissions sources like wood-burning biomass. He said that change raised the state’s emissions levels on paper considerably, but also made them more accurate, and thus, in theory, more attainable.

In the same vein, Krakoff said he hopes regulators will reconsider adding targets for each source of emissions, showing different stakeholders exactly what their role will be in achieving the larger state goals.

“Maine, I think, is a leader in terms of these mandatory greenhouse gas emissions that are there in the statute,” he said. “The hard part is obviously getting to that.”