The five boroughs’ oldest gay bar, Julius’, became a New York City landmark on Tuesday, thanks to a yearslong push by advocates and a unanimous Landmarks Preservation Commission vote.

The commission voted in favor of historic designation for the Greenwich Village bar during a virtual hearing Tuesday morning, with one commissioner, Wellington Chen, calling landmark status “long overdue.”

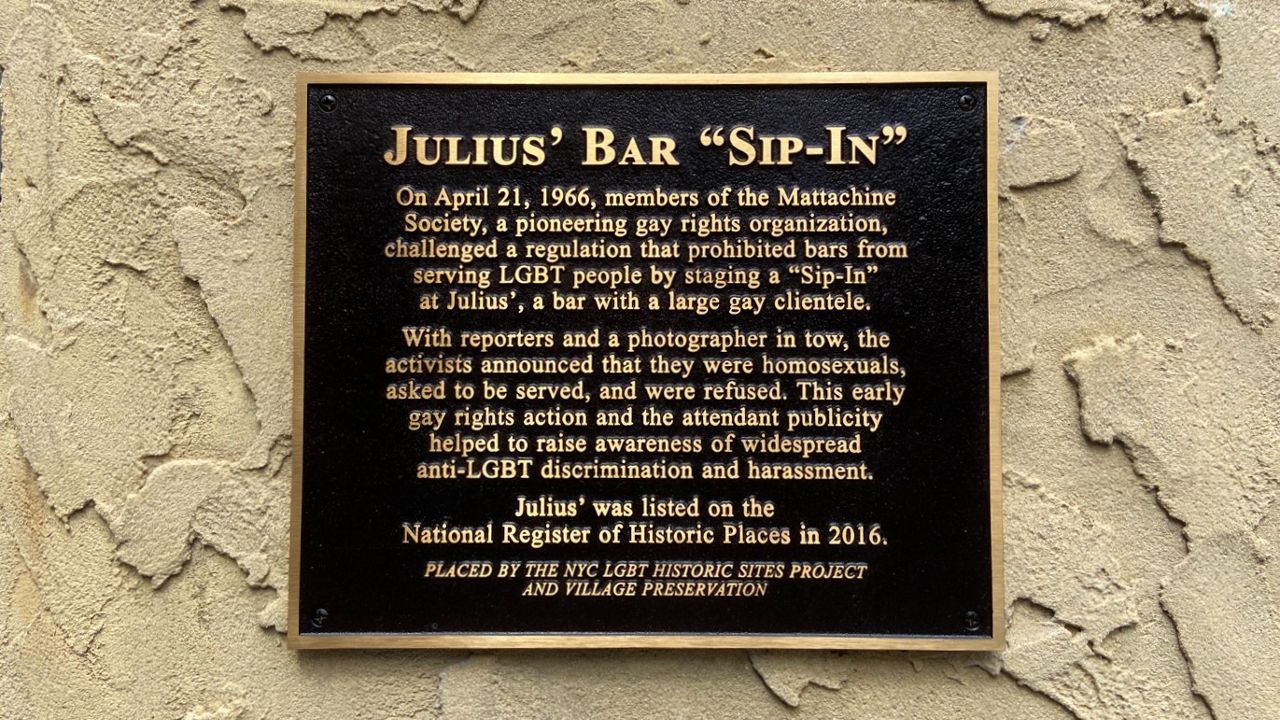

In 1966, three members of the Mattachine Society — a gay rights organization — held a “Sip-In” at Julius’ protesting a rule that made it illegal for bars to serve gay people.

What You Need To Know

- The five boroughs’ oldest gay bar, Julius’, became a New York City landmark on Tuesday, thanks to a yearslong push by advocates and a unanimous Landmarks Preservation Commission vote

- The commission voted in favor of historic designation for the Greenwich Village bar during a virtual hearing Tuesday morning, with one commissioner calling landmark status “long overdue"

- In 1966, three members of the Mattachine Society — a gay rights organization — held a “Sip-In” at Julius’ protesting a rule that made it illegal for bars to serve gay people

Advocates had long since hoped to see the bar on West 10th Street become a landmark, citing its pre-Stonewall significance to the city’s LGBTQ rights movement.

“It has taken all this time, all these decades, and kudos for persistence and tenacity, and getting, you know, as the mayor likes to say, getting the job done,” Chen said at the hearing.

“As the country seems to be grappling with going backward in terms of acceptance and inclusion, I just want to say, bravo, New York, for bringing this one to the forefront,” Commissioner Michael Devonshire added. “And may there be many more.”

The Arts and Crafts-style building that houses Julius’ was originally built in the early 1800s, as three separate buildings that were eventually combined, LPC Director of Research Kate Lemos McHale said at a public hearing in September. Julius’ bar itself opened years later, in 1930.

At Tuesday’s hearing, Commissioner Michael Goldblum noted that granting landmark status to buildings like Julius’ is uncommon for the LPC.

“What’s interesting about it is that the building is an ugly building, in its current form. It’s very debased, and it does not resemble the historic model that is usually followed by the commission,” Goldblum said. “And that’s what I think is great about it, because by designating this as the period of significance, it holds onto a piece of New York that is disappearing — and that’s the grungy part, you know, the ‘50s, ‘60s, ‘70s, when going down in this neighborhood was, you know, you were taking a risk.”

“It’s really about the history, and its being different, its being ugly, its being weird, is kind of the point,” he added. “And I think that’s a really beautiful thing.”

While the city’s landmark designation process does include a City Council vote, the LPC’s vote immediately designates Julius’ a landmark, conferring it with protection under the city’s Landmarks Law.

In a statement on Tuesday, Village Preservation Executive Director Andrew Berman called the vote “a huge step forward in recognizing our city’s history as a refuge and home to the country’s largest LGBTQ+ community, and to our city’s crucial role in advancing civil rights movements and embracing and supporting marginalized communities.”

Village Preservation sent a letter to the LPC asking it to recognize Julius’ as a landmark in January 2013.

“This is an integral part of New York and American history, and these stories and places must be honored and preserved,” Berman said Tuesday. “We praise the city for taking this long-overdue action today, and urge them to keep going.”