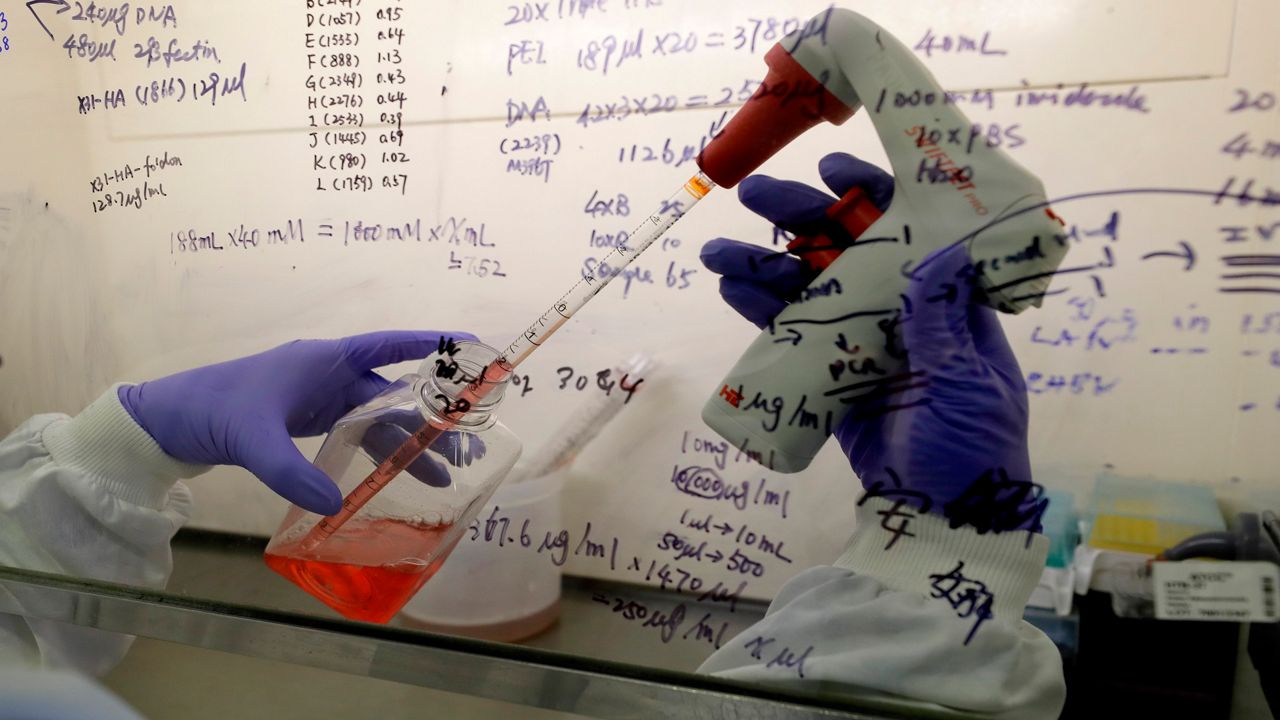

MILWAUKEE — Over the past year and a half, the scientific world has seen a steady flow of research updating what we know about the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, and how it affects humans.

Because the virus is so new, researchers are still grappling with many questions about its function. And because of the nature of the scientific process, no single study can completely answer those questions. Instead, new research is constantly challenging our understanding of the pandemic.

Here, we explore some recent studies that have shed new light on the virus.

Research suggests vaccinated people can spread delta, too

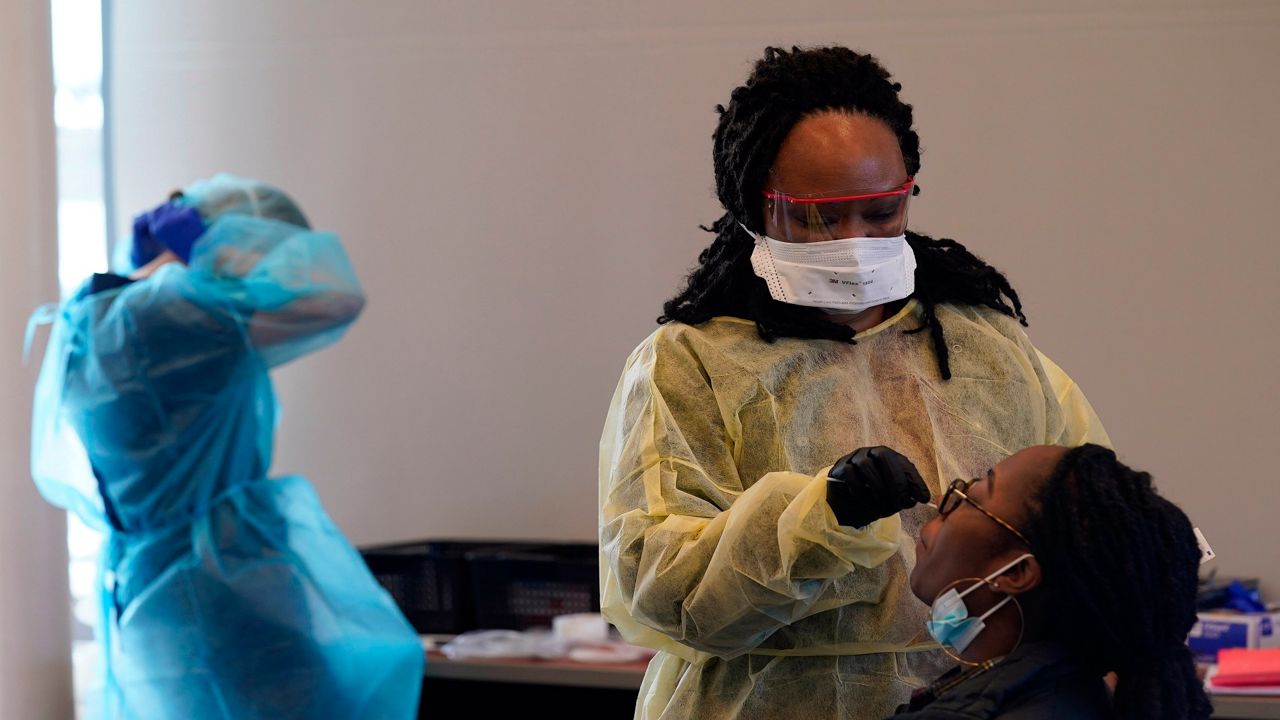

Fully vaccinated people who get a COVID-19 infection still carry a lot of virus around — maybe just as much as unvaccinated people who get sick, according to some recent studies.

A CDC study published in August looked at samples from an outbreak in Provincetown, Mass., where hundreds of vaccinated people tested positive.

To compare the viral load — the amount of coronavirus in each sample — researchers used a measurement called a cycle threshold (Ct) value. Essentially, the Ct value measures how quickly the test “notices” that a sample is positive; that recognition happens sooner if there’s more virus present.

The study found high viral loads even for breakthrough cases — which “raised concern that, unlike with other variants, vaccinated people infected with delta can transmit the virus," CDC Director Rochelle Walensky said in a statement.

Another preprint study from UW-Madison researchers came to a similar conclusion. After looking at COVID-positive samples from vaccinated and unvaccinated Wisconsinites, scientists found that both groups carried similar, high levels of virus.

THe UW scientists were also able to grow infectious virus from breakthrough case samples, another clue that vaccinated people could get others sick.

There’s some evidence that vaccinated people may see their viral loads drop more quickly after an infection — which would mean they wouldn’t spread the virus for very long after getting sick. And fully vaccinated people have a lower chance of catching COVID-19 in the first place, so they’re overall less likely to spread the virus compared to unvaccinated people.

Still, with delta fueling the biggest U.S. surge in half a year, health officials are encouraging everyone to take extra precautions, no matter their vaccination status.

The CDC recommends that if you live somewhere with “high” or “substantial” COVID-19 transmission — as in, most of the country right now — you should be wearing a mask indoors, even if you’ve gotten your shots.

Booster shots for the immunocompromised get the go-ahead — and more could be on the way

A third dose of COVID-19 vaccine is on the way for some Americans, after federal officials gave the green light for booster doses for the immunocompromised.

The FDA and CDC last week recommended that people with “moderately to severely compromised immune systems” should get an extra Pfizer or Moderna shot to help spur better protection from the virus.

Growing evidence has shown that, for people with certain conditions that weaken the immune system, even two shots of an mRNA vaccine won’t offer strong protection against the virus.

That group includes organ transplant recipients, who take medicine to suppress the immune system so their bodies don’t reject their new organs.

One study found that, even after two vaccine doses, almost half of transplant patients didn’t show an antibody response. Another study found that a third shot led to a big immune boost for these vulnerable patients.

According to CDC guidance, other conditions that qualify patients for a booster dose include: Treatment for tumors or blood cancers, advanced or untreated HIV, treatment with drugs that suppress the immune response, stem cell transplants, or other conditions that cause immunodeficiency.

The CDC recommends that these patients get a booster dose of the same mRNA vaccine they originally received, at least four weeks after their last shot. There’s no guidance yet on extra shots for those who got the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

Boosters for other Americans might be offered in the coming months, too: Federal health officials are expected to recommend an extra mRNA dose for everyone eight months after their original shots, The New York Times reported Monday. The boosters might get a wider rollout as soon as mid-to-late September, officials told The Times.

But for now, third doses are only allowed for these high-risk patients, who make up around 3% of the U.S. population, according to the CDC.

"At a time when the delta variant is surging, an additional vaccine dose for some people with weakened immune systems could help prevent serious and possibly life-threatening COVID-19 cases within this population," Walensky said in a statement.

Keeping tabs on breakthrough cases

More than half of Americans are now fully vaccinated against COVID-19, according to the CDC. So just how protected are they against the current surge of delta cases?

There’s still a lot to learn about breakthrough infections — though some recent research sheds light on how fully vaccinated people can think about their risk levels.

As of late July, fully vaccinated people were making up small shares of COVID-19 infections in the states that were tracking breakthrough data, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis.

Breakthrough cases made up around 6% of infections in Arizona, the highest share in any state. In Connecticut, breakthrough cases made up only around 0.15% of new infections.

Nationwide, the CDC is tracking severe breakthrough cases that lead to hospitalization or death, but not mild or asymptomatic breakthrough cases.

According to the CDC’s data, around 1,600 people have died from breakthrough coronavirus cases. That means under 0.001% of all fully vaccinated Americans have died from COVID-19.

Around 7,600 people have been hospitalized with breakthrough cases, the CDC reports — making up under 0.005% of all fully vaccinated people.

So far, then, severe breakthrough cases are rare, but possible. And research suggests that those who are more vulnerable to COVID-19 in general are also more at risk for a severe case after vaccination.

In Israel, researchers looked at 152 patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 even after they were fully vaccinated.

Almost all of these severe breakthrough cases — around 96% — involved comorbidities like hypertension, diabetes or congestive heart failure, according to the study. Around 40% of the hospitalized, fully vaccinated patients were immunocompromised.

There’s still a big question mark of whether vaccinated people who get milder cases could face “long COVID” symptoms.

Another study in Israel included 39 fully vaccinated health care workers who tested positive. Among these breakthrough infections, most cases were either mild or asymptomatic — but around 19% did lead to lingering symptoms, including loss of smell and fatigue, at least a month and a half later.

Vaccination is still the best way to protect against surging coronavirus cases, including the delta variant, health officials stress. But even our excellent vaccines can’t offer perfect protection.

"You could imagine your vaccine providing a bit of a force field, but that's not the case anymore," Yale vaccine expert Saad Omer told NPR. "It's still pretty strong armor. But it's penetrable armor."

Other news to note:

A review of different studies on long COVID-19 found that 80% of recovered patients developed some lingering symptoms. The most common long-term symptoms were fatigue, headache and attention disorder.

The CDC encouraged pregnant women to get a COVID-19 vaccine, citing new data that found getting the shots did not increase the risk of miscarriage.

A preprint study found that the Pfizer vaccine’s efficacy rate fell to 84% after half a year, but kept a 97% rate of protection against severe disease.

Air pollution from wildfire smoke may have exacerbated COVID-19 cases in the American West, leading to thousands of extra cases, according to a Harvard study.