This story is part of our Climate Connections series, highlighting how a changing climate is affecting our state.

MILWAUKEE — Wisconsin has no shortage of natural beauty to soak up. But it turns out us humans aren’t the only ones enjoying the view.

“All of our beautiful outdoor spaces where we want to be, also are the spaces where mosquitoes and ticks want to be,” said Lyric Bartholomay, a professor at UW-Madison’s School of Veterinary Medicine.

What You Need To Know

- Wisconsin is a leading state for Lyme disease and threatened by other vector-borne illnesses like West Nile virus

- Lyme rates have doubled in the past decade, and could keep rising as the state is expected to get warmer with climate change

- With later freezes and earlier thaws, ticks and mosquitoes could be active for a longer part of the year

- New disease-carrying species could move into Wisconsin in a warmer climate — though the shifts could also throw their ecosystems off balance

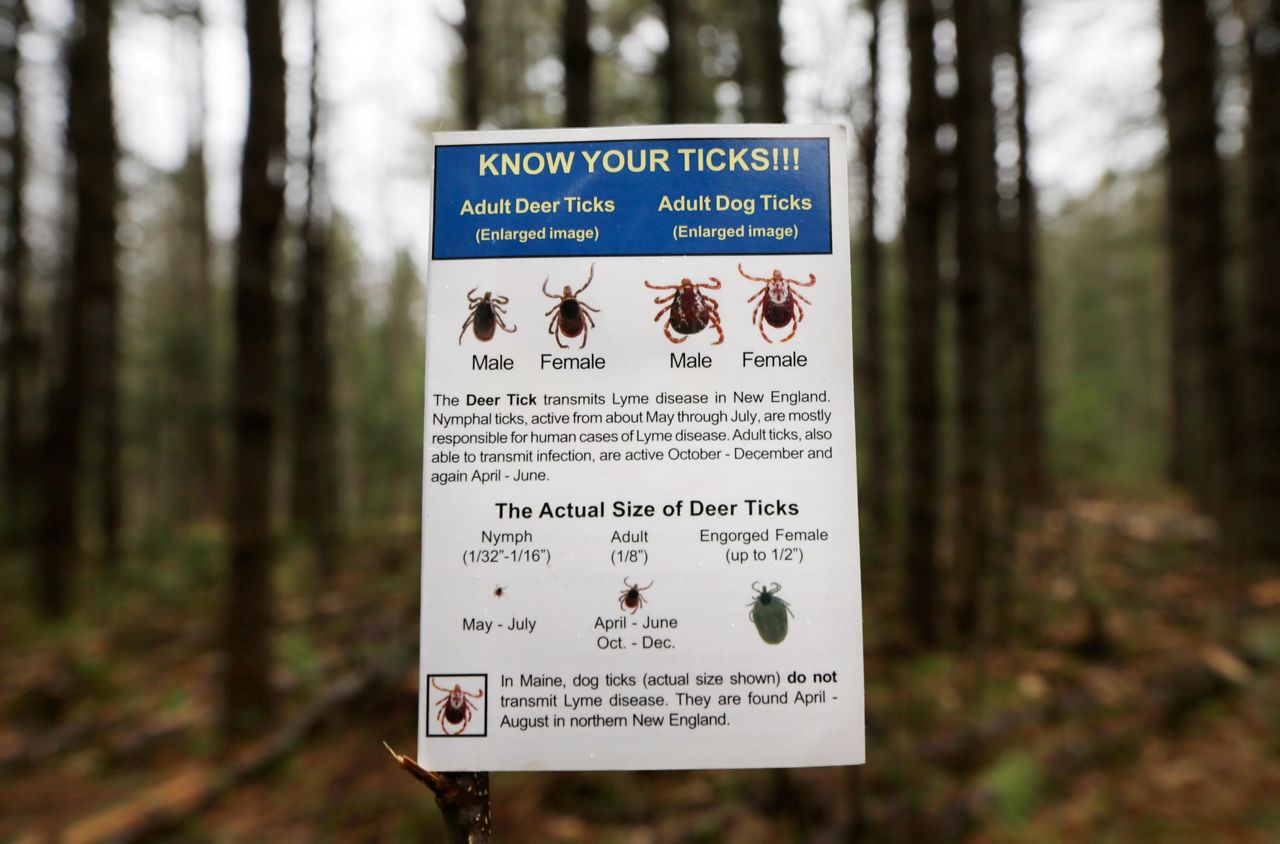

These bloodsuckers aren’t just an annoyance for your day in the woods: Some species of ticks and mosquitoes in the state serve as vectors that can infect humans with dangerous diseases. Wisconsin is already a leading state for cases of Lyme disease, which is spread by the bite of the deer tick and can lead to chronic symptoms in some people.

And as temperatures rise in Wisconsin, the risk of catching a bug from one of your bites could grow, too. Warmer weather could help ticks and mosquitoes stay active for a longer part of the year, and even bring new disease-carrying species to our state — though there’s still a lot to learn about how these tiny creatures will react to a changing climate, Bartholomay said.

“It’s not insignificant, the threat associated with bloodsuckers in our state,” Bartholomay said.

A brief history of Wisconsin’s bloodsuckers

In Wisconsin, we’ve seen a few waves of vector-borne illnesses emerge over the years, Bartholomay said.

Back in the 1960s, an outbreak of mosquito-borne disease started showing up in kids in La Crosse. The virus isn’t very common in Wisconsin these days, but still shows up in small numbers — and now goes by the name La Crosse encephalitis.

“This really put Wisconsin on the map as it relates to mosquito- and tick-borne diseases,” Bartholomay said.

The state has also seen some cases of West Nile virus — another mosquito-borne disease that swept across the U.S. in the 2000s — and in recent years has reported dozens of cases of the rare Jamestown Canyon virus, Bartholomay said. Overall, the state has more than 50 species of mosquitoes, and the diseases they carry are a big threat to Wisconsinites, she said.

Still, when it comes to vector-borne diseases in the state, ticks — and especially Lyme disease — have quickly become the central threat, said Victoria Gillet, a Milwaukee-based primary care physician and member of Wisconsin Health Professionals for Climate Action.

“Wisconsin is a hotbed of Lyme disease,” Gillet said, even though “it wasn't always that way.”

Lyme disease cases began to turn up in the state near the end of the 20th century. Though the disease started off pretty small, numbers “kind of exploded” in the early 2000s, said Rebecca Osborn, a vector-borne disease epidemiologist with the Department of Health Services.

Other tick-borne illnesses, including anaplasmosis and babesiosis, have also been growing more common, Osborn said. The DHS reported an estimated 3,076 cases of Lyme disease for 2020 — a number that has more than doubled over the last 10 years.

“We have seen a really significant increase in cases of Lyme disease in the past few decades,” Osborn said.

A few different factors could be pushing our Lyme rates higher, she said. With more awareness and testing, we might be catching a higher share of the cases that are out there.

Other changes in how we interact with Wisconsin’s nature — like people cutting down forests, moving into rural areas or causing shifts in animal populations — may have also driven the uptick, experts said. And the deer ticks that spread Lyme and other diseases have fanned out across the state: They were originally limited to the northwest, but have now turned up in every county in Wisconsin.

But research shows that around 10% of the Lyme uptick is a direct result of global warming, Gillet said. And as the climate keeps changing, so will our risks from ticks and mosquitoes.

“What we do know is increasing temperatures are kind of really bad news for vector-borne disease spread in Wisconsin,” Osborn said.

More time and space for ticks?

On the whole, Wisconsin’s climate has become warmer and wetter in recent decades — a trend that’s expected to continue as the climate keeps shifting, according to the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts.

For the tiny species that spread diseases, weather plays a big role in determining life cycles, Osborn said. Deer ticks and many other vectors are “generally active at temperatures above freezing,” she said — moving around the forest and looking for animals to latch onto.

Typically, when temperatures drop in the fall, ticks and mosquitoes drop off too — and we don’t have to worry about them until spring warms us up again, Osborn said. In a warming climate, though, the vectors might be able to stay active for a bigger chunk of the year, which means more opportunities for them to interact with humans.

“We think right now of Lyme as being sort of a spring-summer illness,” Gillet said. “But as we have earlier and earlier thaws, and later and later freezes, the amount of time of the year that you're going to be able to be bitten by a tick is going to increase dramatically.”

Since the 1970s, the mosquito season in Wisconsin has already become at least two weeks longer, according to a report from Wisconsin researchers last year.

There’s some evidence that warmer conditions can help vectors reproduce faster and spread disease more easily, Osborn said. Plus, a warmer climate for Wisconsin could open doors for even more bloodsucking species to move into our state — and bring new diseases along with them, experts said.

Our harsh winters have warded off some disease-carrying critters in the past. Those winters are getting more mild as the years go on, though, and we’re already seeing some concerning species move northward, Osborn said.

The lone star tick — whose bite can cause some nasty diseases, including an allergy to red meat — is still rare in Wisconsin, but reports seem to be increasing by the year, she said. And the invasive Aedes albopictus mosquito, which can carry tropical diseases, has been detected in Wisconsin after making its way north in recent years, though it doesn't seem to be established in Wisconsin just yet, Bartholomay said.

“Warmer temperatures will likely make it so the state becomes hospitable to things we haven't seen before,” Bartholomay said.

Still, while “change is inevitable,” it’s hard to predict exactly how these species will respond to our changing weather patterns, Bartholomay pointed out.

Even as a warmer climate may attract new species from the south, it could also push away critters that need the cold winter temperatures in their life cycles, she said.

And, of course, vectors don’t live in a vacuum: They rely on the rest of the ecosystem to survive after they hatch, whether it’s mosquitoes feeding on flower nectar or ticks latching onto mice and deer. So, while changing weather patterns could mean more active months for bloodsuckers, they could also throw off the fragile balance of their life cycles, Bartholomay said.

“All those things are things we notice, and they either disrupt our daily lives or they disrupt our livelihood,” she said. “But when you're looking at it from the perspective of a tiny, cold-blooded animal, the impact is really magnified.”

Even so, Bartholomay said, “I think they’ll persist. They find a way. You know, bet on the vector.”

Living with Lyme

As a health care provider, Gillet said she starts thinking about Lyme disease from the moment Wisconsin thaws out until we freeze back up again. In the future, that could mean having Lyme at the front of her mind all year round — and getting everyone to understand that risk will be key, she said.

“One of the stresses with climate change is that things change, and people don't expect them to change,” Gillet said. “And so, people's behavior doesn't change.”

Tick-borne diseases can be especially tough because there aren’t a lot of ways to fight them on a community-wide level, Osborn said. Once tick populations show up in an area, they’re hard to get out; once Lyme starts spreading, it’s tough to stop it.

Personal prevention measures will be key to prevent bites from ticks and mosquitoes in the first place, experts said. That includes wearing long sleeves, using repellent, checking for ticks and avoiding vectors’ favorite spots — like tall grass for ticks or standing water for mosquitoes.

“A lot of this is really sort of the responsibility of the individual,” Osborn said. “Unfortunately, it doesn't stop all tick bites, and it doesn't stop all transmission.”

The issue of chronic Lyme disease makes the possibility of more deer ticks extra dangerous, Gillet added. While Lyme is easy to treat with antibiotics if you catch it right away, some people may suffer with long-lasting symptoms — like generalized pain, numbness, brain fog and skin irritation — if they don’t get that treatment early on.

Scientists still don’t have a full explanation for why some Lyme patients get stuck with these chronic symptoms, Gillet said. Some researchers are working on vaccines to prevent Lyme and other tick-borne diseases, including an mRNA shot that recently reported promising results.

But for now, “the best way to avoid chronic Lyme is to not get infected,” Gillet said — which could be a tougher task in a warmer Wisconsin.

Bartholomay stressed that there is still a lot to learn about how a changing climate will affect Wisconsin’s ticks and mosquitoes. But in a state that’s already one of the leading states for Lyme, the idea that risk could keep rising is “certainly concerning,” Osborn said.

Gillet said she’s hopeful that understanding these health risks could help motivate people to take action against climate change. After all, a lot of people’s health is determined long before they step into a doctor’s office, she said — and we all play a role in deciding what our public health risks will look like in the years to come.

“Things are going to get worse before they get better,” Gillet said. “And the amount that things will get better eventually really depends on us now.”