MILWAUKEE — Wisconsin researchers don’t have a crystal ball to see where the COVID-19 pandemic is heading. What they do have: Bottles and bottles of sewage.

What You Need To Know

- Researchers are tracking COVID-19 through sewage samples across Wisconsin, which don't depend on people going out for tests

- Wastewater tracking data is starting to trend down for many Wisconsin cities

- Researchers are also tracking variants, like delta and omicron, in sewage, and hope to start identifying new versions of the virus

- The wastewater data may play a key role in less acute phases of the pandemic

For more than a year now, scientists in the Badger State have been tracking the SARS-CoV-2 virus through wastewater. That’s possible because infected people don’t just breathe the virus out through their airways — they also flush it down the toilet in their feces.

And while a swab up the nose may still be the best way to see if a single person is sick, researchers said the sewage data offers important clues to the pandemic’s wider trends.

“Wastewater monitoring can give you a bigger picture,” said Becca Fahney, an environmental toxicologist at the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene. “It can tell you more of what's going on in your community without testing individual people.”

These days, that picture is starting to look less grim. After months of omicron-driven surges, Wisconsin’s wastewater data — which is collected by teams at the State Laboratory and UW-Milwaukee — is showing some signs of a turnaround.

Long after we’re past our current peaks, though, we’ll still have reason to be digging around in the state’s sewage, said Sandra McLellan, a professor at UW-Milwaukee’s School of Freshwater Sciences whose lab has been collaborating on the wastewater tracking.

“I don't think the coronavirus is going away,” McLellan said. “I think it's going to become part of what we're exposed to on an ongoing basis. So, I think, it's going to be really useful to continue that surveillance going forward.”

Sewer clues

When the pandemic first kicked off, Wisconsin researchers were quick to “jump on the wagon” of wastewater surveillance, said Dagmara Antkiewicz, a scientist at the State Laboratory of Hygiene.

“As a public health lab, we felt that it's in our obligation to be ready for whatever the public health needs are,” Antkiewicz said.

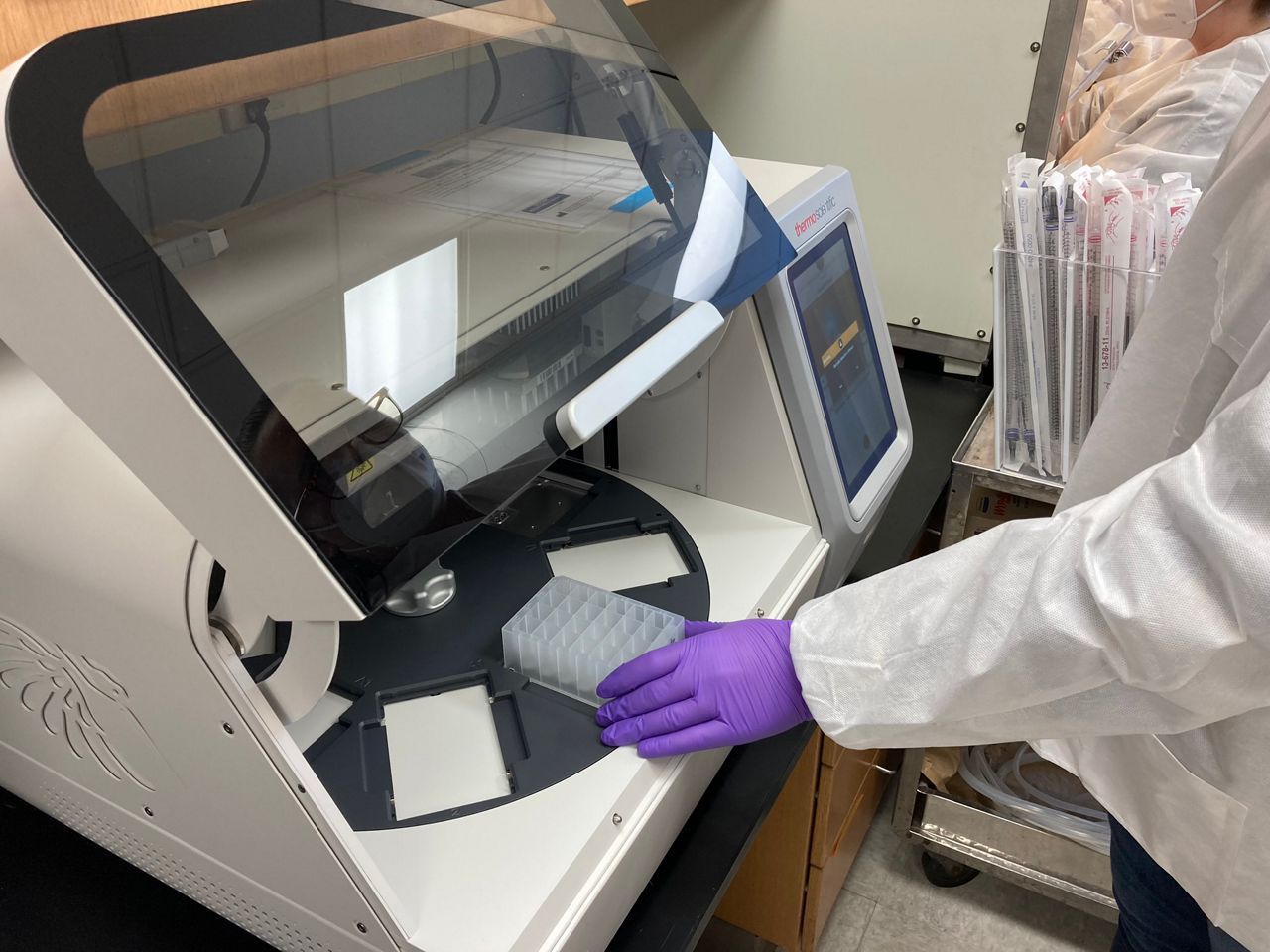

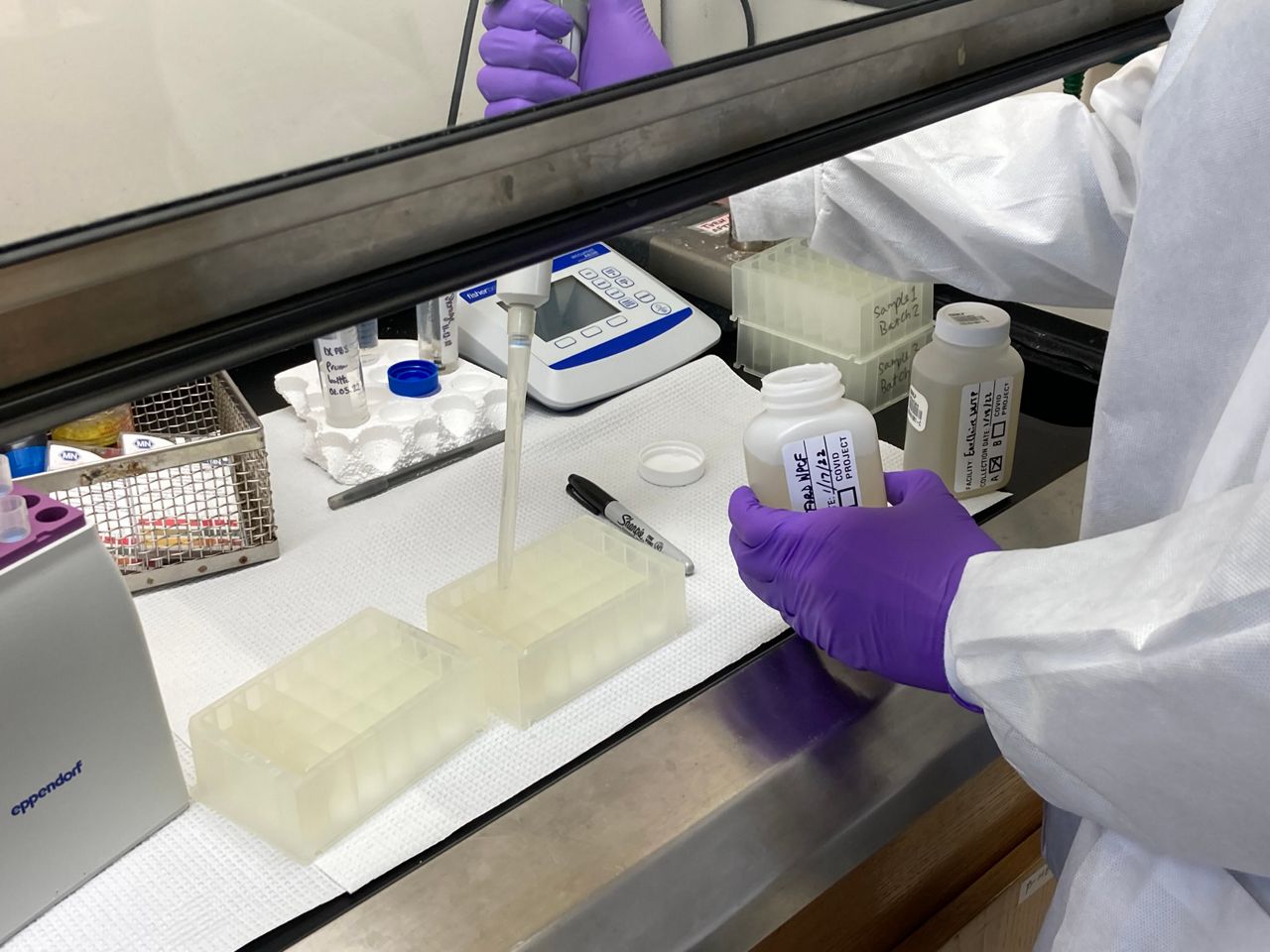

By December 2020, researchers had worked with the Department of Health Services to launch a statewide dashboard. Dozens of wastewater treatment plants now send bottles of sewage to the State Laboratory and UW-Milwaukee, where researchers figure out how much virus is in a given sample — and therefore, how much COVID-19 is in a given community.

While other states have since set up their own tracking efforts — and the CDC has said it’s working to ramp up wastewater surveillance on a national scale — Wisconsin’s system was one of the first and one of the biggest, McLellan said.

“I don't think I'm biased,” McLellan said. “But I think Wisconsin is No. 1 in this.”

Since then, the wastewater data really has mirrored Wisconsin’s testing outcomes throughout the year, McLellan said.

Viral wastewater levels dipped in the summer, when fewer people were testing positive, Fahney pointed out. And in December, as omicron took over, researchers saw the highest-ever levels of virus in Wisconsin’s sewage.

Early on, researchers were cautious about relying on this new science — Antkiewicz said figuring out their methods sometimes felt like “we were building the ship as we were sailing.” But McLellan said the past year’s worth of evidence has made her more confident in relying on the wastewater data.

For a lot of Wisconsin right now, that’s good news. As of the DHS dashboard’s latest update on Tuesday, sewersheds in many of Wisconsin’s cities were seeing a decrease — including Milwaukee, Green Bay, Kenosha, Racine and Appleton.

“We're not out of the woods,” McLellan said. “But there is a slight downward trend, so we hope we keep seeing that.”

Madison was one of the handful of areas still seeing an increase in its wastewater levels in the latest update — though McLellan pointed out that some of the uptick could have to do with university students moving back to campus.

One of the big perks of looking at wastewater data is that it captures everyone in a given area, not just those who go out to get a test, scientists pointed out.

“When it comes to representing a community, it’s pretty unbiased,” Antkiewicz said.

Even if people don’t have easy access to a COVID-19 test site, their sewage gets mixed in with everyone else’s, Fahney said. And if a bunch of people rush out to get swabbed during a surge, the wastewater data won’t be inflated by the number of tests given out, McLellan said.

“That's the value of wastewater: It takes the testing dynamics out of it,” McLellan said. “So we really can compare apples to apples.”

Flowing forward

With Wisconsin hopefully on the tail end of its omicron surge, we might soon be entering a less extreme phase of the pandemic — one where wastewater data could play a key role.

“Remember, the acute phase of the pandemic is not forever,” Ben Weston, chief health policy advisor for Milwaukee County, said at a briefing last week. “So once we get into that more surveillance phase, watching for variants to crop up, watching for areas of the community to have higher disease burdens, the sewershed data will be really valuable.”

When COVID-19 drops to lower levels, people might be less likely to go out and get tested, Antkiewicz pointed out. Plus, as more people rely on at-home test kits — and don’t always report their results to public health — the testing data alone might not paint a full picture of infections, McLellan said.

“We might see that we’re going to lose that eye we had on testing statistics,” McLellan said. “The wastewater will really help us keep an eye on what’s going on.

Researchers have cut down on the number of plants they’re sampling from — they’re now at around 50 sites, instead of more than 70 at their peak, Antkiewicz said. But McLellan said the smaller number of plants can act as “canaries” to sound an early alarm when cases might be heading up in an area.

Over the past year, researchers have also been able to start tracking variants through wastewater surveillance. McLellan said her team is able to target key mutations of different variants in their samples — like in December, when they watched omicron take over sewage samples with “really surprising” speed.

For now, scientists are only able to test wastewater for variants that we already know about. The next goal is to figure out whole genome sequencing for wastewater samples, so we could look for any brand-new variants that could be floating around in our pipes, McLellan said.

“That's where we might get a little bit more of an early warning,” she said.

Getting a full sequence out of wastewater can be tricky, because genetic material tends to be more fragmented in these samples, Antkiewicz said. But McLellan is hopeful that this process will be added to the mix within the year.

The researchers are already thinking beyond our current pandemic, too. With some tweaks, Fahney said, the wastewater surveillance technology could also be used to track other viruses, like flu and RSV, or even keep an eye out for antibiotic resistant organisms.

Now that we have a better handle on this kind of wastewater monitoring, we could be looking to the sewers for all kinds of health clues, researchers said.

“We've had so many jumps from animal to human, in terms of diseases, that I'm sure there is another one that's going to come,” Antkiewicz said. “People will not travel less. The globe will not be less populated. So this will just become one of the tools in the toolbox of monitoring health.”