Editor's Note: This story is the first of a two-part series on gerrymandering.

TEXAS — A seven-year legal battle over Texas’s legislative maps largely ended in May when the Supreme Court rejected almost all claims that Republican lawmakers in the state had drawn electoral districts to intentionally dilute minority voters’ influence — otherwise known as racial gerrymandering. The decision in Abbott v. Perez rounds out a string of defeats at the high court this term for voting-rights advocates.

A month before that ruling, the Supreme Court asserted that partisan gerrymandering should be left to states. In a 5-4 decision along traditional conservative-liberal ideological lines, the Supreme Court ruled that partisan redistricting is a political question — not reviewable by federal courts — and that those courts can't judge if extreme gerrymandering violates the Constitution.

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the conservative majority that excessive partisanship in the drawing of districts does lead to results that "reasonably seem unjust," but he said that does not mean it is the court's responsibility to find a solution.

Gerrymandering refers to the practice of redrawing voting district boundaries with the intent to favor one party over the other, discriminate against minorities, or, in some cases, maintain the status quo.

The compactness of a district — a measure of how irregular its shape is, as determined by the ratio of the area of the district to the area of a circle with the same perimeter –can serve as a useful proxy for how gerrymandered the district is. Districts that follow a generally regular shape tend to be compact, while those that have a lot of squiggles and offshoots and tentacle-looking protuberances tend to be the most doctored.

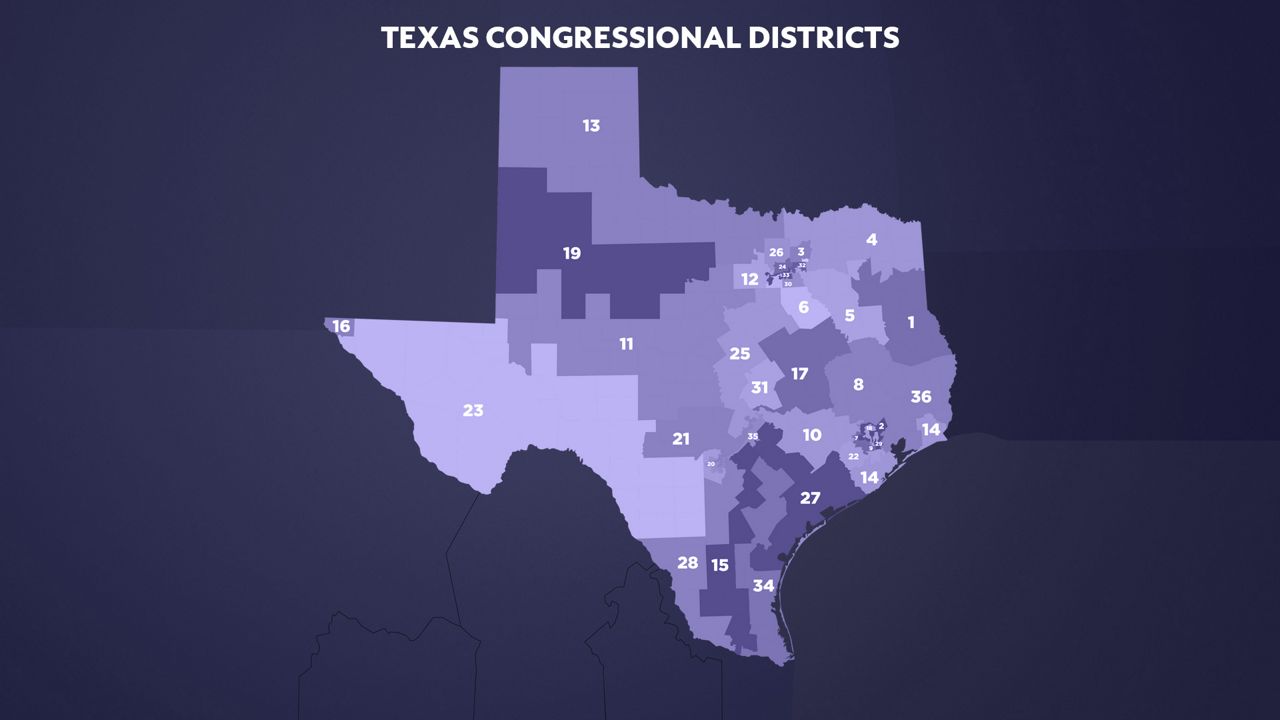

In Texas, where national experts conceded the congressional districts look more like Rorschach inkblots than representative swaths of real estate, the state’s legislative makeup has been impacted by gerrymandering more than any other state, according to a study by the Associated Press.

Texas has been found in violation of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 because of intentional racial discrimination every decade since its enactment. The root of these violations is redistricting, the process of redrawing the boundaries of every congressional and state legislative district to maintain roughly equal populations. This process occurs every 10 years after collecting new census data. A select group within the Texas Legislature is the architect and cartographer of this endeavor.

This is the heart of Texas’s long history of intentional discrimination against voters of color: Analysts say that because voters of color were packed into single districts or broken up across several districts, their voting power is diluted to the point that their votes are rendered ineffective in choosing their political representation.

David Vance, a national media strategist for Common Cause, a D.C.-based watchdog group that fights for representative government, said Texas doesn’t have the best record of creating a fair vote. Gerrymandering, he said, is just one tactic used to silence voters in Texas.

“I think you've seen in the voting process all sorts of efforts to minimize the power of voters of color, and that that's either through some of the sort of racial gerrymandering, discriminatory voter ID laws, and, most recently, limiting ballot drop off points. It’s definitely an unfortunate pattern.”

Like clockwork, the United States conducts a census every 10 years to provide a snapshot of where the nation’s residents live. States use that snapshot to update their legislative maps for population shifts. The U.S. holds federal elections every two years, so those maps are used at least five times before another decennial census starts the process anew. Voters have already cast ballots in three federal elections based on controversial and contested maps drawn after the 2010 census.

The recent iteration of the gerrymandering saga in Texas dates back to 2003 when Rep. Tom DeLay was avenging years of Democratic gerrymandering. He led the unprecedented step of redrawing the state’s congressional districts in the middle of the decade, five years before the census.

“When Republicans took over the state legislature, they sort of smelled blood in the water,” Vance said. “The Republican majority, egged on by Tom DeLay, decided to take their legislative majority for a spin and redraw the districts mid-decade. Their defense was it was sort of a tit for tat. You saw Democrats also gerrymander in Texas for decades before that.”

In the spring of 2003, Texas Republicans, who were now dominant in both the State House and Senate, proposed a new congressional map that promised to add between five and seven new Republicans to the Texas delegation. At the time, DeLay said that with 57 percent of Texas voters backing Republicans for Congress, it was only fair that the GOP control more than 15 of the 32 seats in the U.S. House. If a mid-census redistricting was necessary to align the seats with the popular vote, Republicans argued, so be it.

Texas law required that two-thirds of the 150-member body be present to conduct legislative business. The Democrats, who numbered 62, could stop the legislation simply by not showing up. So most of them took off for Oklahoma. There was some precedent for this kind of action in Texas. In 1979, a group of liberal state senators, known as the Killer Bees, fled the state to deprive the majority of a quorum in a dispute over the date of the Texas Presidential primary. This time, in 2003, the House Democrats were dubbed the Killer D’s. Sen. John Whitmire, of Houston, decided that the effort had become futile, and returned to Texas for the Labor Day weekend. The map passed, but not without a phalanx of legal battles.

Since the passage of the Voting Rights Act, in 1965, most legal fights about redistricting have concerned the rights of racial minorities. DeLay expected such a challenge to the 2003 Texas map, and he was ready with a preemptive defense. “Minority rights have been protected,” he said at a press conference after the plan was ratified. He asserted that the number of Hispanic representatives could grow from six to eight, and the number of African-Americans from two to three. (These predictions were, for the most part, accurate.)

From the beginning, it was evident that the agenda of the Republican mapmakers in Texas was more political than racial. Shortly after the redistricting plan passed, Joby Fortson, an aide to Republican Rep. Joe Barton, sent a candid email to a group of colleagues that makes this point more clearly than any public statement issued by the participants.

The memo, which was disclosed in the course of subsequent litigation, offers a “quick rundown” on each of the seats in the delegation. Fortson begins his description of the district where Martin Frost, the senior Democrat in the state, would have to run with the words “Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha. . . . His district disappeared.” As for another Democratic incumbent, Nick Lampson, Fortson says, he and a GOP incumbent “are drawn together in a Republican district.” (Lampson lost, too.) “This is the most aggressive map I have ever seen,” Fortson concludes. “This has a real national impact that should assure that Republicans keep the House no matter the national mood.”

The most recent gerrymandering battle in Texas stems from a legal challenge by a group of Black and Hispanic groups who alleged the 2011 version of the district maps bolstered white Texans' voting power. From 2000 to 2010, Texas grew by 4 million people, and 90 percent of them were minorities. Not a single minority group received an additional seat in Congress as a result of that growth.

With the 2012 election imminent, a federal court made minor alterations to the 2011 map for use in that year’s races.

When Texas Republicans returned to the legislature in 2013, they adopted the court’s interim maps as the permanent maps, with only a few alterations. After the courts later ruled that the 2011 maps had been drawn with discriminatory intent, the state argued that the 2013 maps weren’t affected because they had been largely drawn by the courts themselves. In effect, Republicans had laundered a racially gerrymandered map through the judicial system, Vance said.

In a forceful dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor said the majority had manipulated prior rulings and the evidentiary record to reach its desired outcome. “As a result of these errors, Texas is guaranteed continued use of much of its discriminatory maps,” she wrote, joined by justices Stephen Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Elena Kagan. “This disregard of both precedent and fact comes at serious costs to our democracy.”

At times, Sotomayor wrote in her 46-page dissent, the majority selectively quotes evidence that exonerates Texas lawmakers of discriminatory intent. In other instances, she asserted, the court’s conservatives ignore a broad swath of the factual record that suggests the state’s Republicans sought to preserve the 2011 maps’ flaws as much as possible when drawing the 2013 maps.

Soon after the original 2010 redistricting plan was redrawn in 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the preclearance law in Shelby v. Holder in 2013, giving Texas a new unchecked power in creating voting laws and passing redistricting plans. The day after the preclearance safeguard was removed, a modified redistricting plan was signed into law. An analysis by AP showed that the plan helped Texas Republicans win more U.S. House seats through redistricting than any other state.

Fort Worth Democratic Rep. Marc Veasey represents what the Washington Post recently called "one of the most gerrymandered districts in the country. Veasey said the Supreme Court's decisions to allow gerrymandering and Texas have created a system in which the elected officials are choosing their constituents, not the other way around.

“Republicans have been very gross in their gerrymandering and their racial gerrymandering,” Veasey said. “I think that the Supreme Court has definitely erred. I really hope that with the blatant attempts right now that tries to undermine African American and Hispanic voters – the things that Trump is saying about voting, about voter fraud, the things that governor Abbott is doing with these drop-off mail ballot boxes – I hope that it wakes them up."

On Thursday, part II of this series will focus on specific laws that have been impacted by gerrymandering and why the practice is so difficult to overturn in the courts.