DALLAS — A Texas Supreme Court ruling from late June ensured railway company Texas Central can exercise eminent domain to seize land without owner’s consent for the Dallas-to-Houston bullet train in the works.

The 5-3 ruling is a win for the Dallas-based company, which is planning to construct the 240-mile railway to shorten the time it takes to get to Houston from the Metroplex from four hours to an hour and a half. The court’s majority ruled that the company qualifies under the definition of “electric interurban railway,” which grants it the power of eminent domain.

Texas Central Partners, along with its subsidiaries — Texas Central Railroad and Infrastructure, Inc. and Integrated Texas Logistics, Inc. — has only released one statement since the ruling, stating it’s moving forward to a path that it believes will ensure the project’s successful development.

"We thank the Court for its recent thoughtful and considered review of this matter and appreciate the continued support of our investors, lenders, and other key stakeholders, as we continue to advance this important project. Texas Central has made significant strides in the project over the last several years and we are moving forward on a path that we believe will ensure the project’s successful development. We look forward to being able to say more about this at an appropriate time in the near future,” the statement reads.

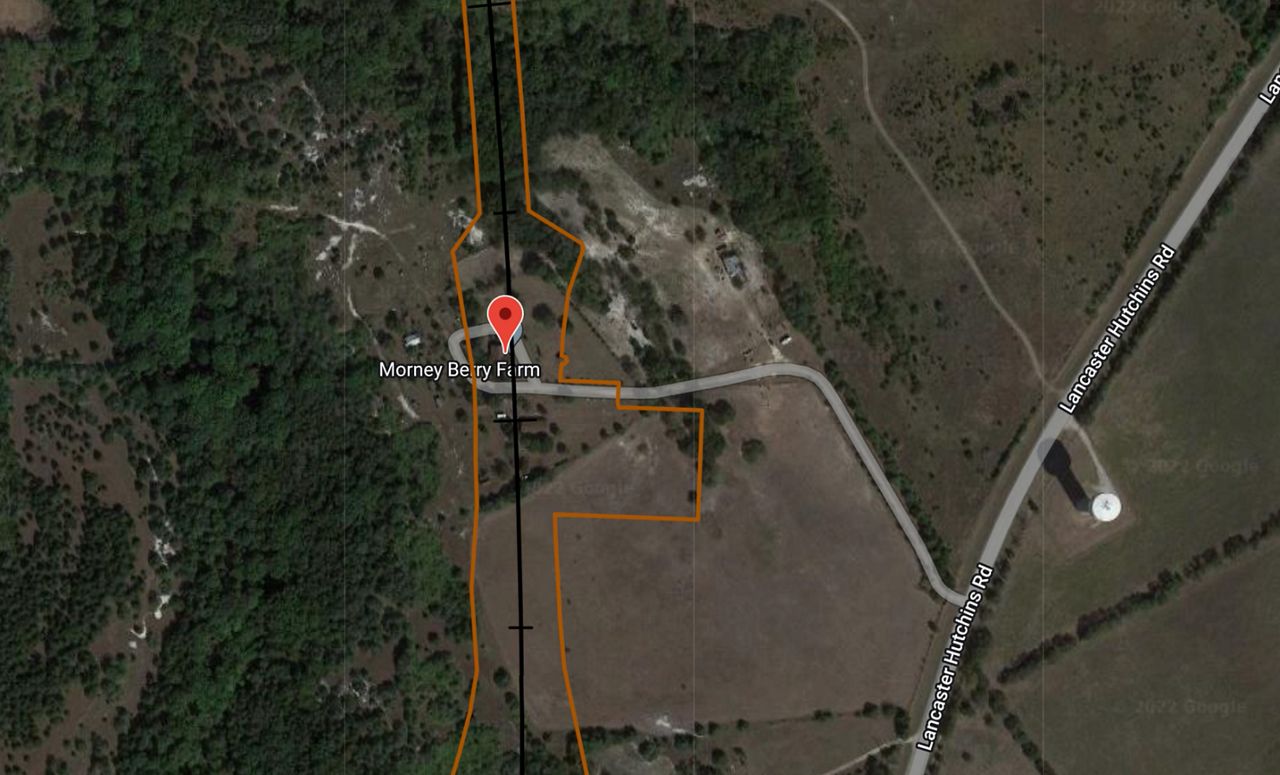

Landowners in the path of this current proposed route say they’re unhappy with the potential future land grab. Jody Berry's family has owned a southern Dallas farm — about 20 minutes from downtown — since 1876 and says she’s never officially been notified by the company that they plan to fracture the farm with a bullet train. The train would cut right through their farm, and Berry says it would destroy everything from the main house to the pavilion and the gazebo, making it obsolete and unable to host any events on property.

“We [are] shocked, because the thing of it is is there was never any notification. So then we started looking around to find different documents to see if it was incorrect or if that was the final route, but it clearly stated within the judgment that that was the final route,” Berry said. “How could people not notify us that this was possibly going to be the route that they would take? And knowing the history of what our great great grandparents went through, as well as what my mom went through to keep the land together and within our family, as well as its significance in the community.”

Berry’s mom Murdine fought for the Morney-Berry Farm in Hutchins back in the late 1900s, suing to get the family’s name back on the farm’s title.

"It's really disconcerting when they tell you it's eminent domain and you have something that your family has worked so hard to keep. And people don't even take that into effect,” Jody Berry said. "Eminent domain always affects those that don't have a voice or their voice is minimal in the grand scheme of things.”

Berry wants what she’s calling “big business” to back off and find another way to route the train. In Texas Central’s Bill of Rights, the company says it’s committed to treating landowners with respect, negotiating in good faith and engaging in a fair and transparent land acquisition process. The company commits to providing landowners with notice to survey and access property, and will make a good faith offer for the land. Berry is calling the company’s bluff, having never been notified up to this point.

“Be aware that you can't keep taking things from people because you feel that they don't have any voice or they don't have any say so. So those underserved groups, older people, people of color, you know, that's not right, and we need to do things the right way,” Berry said. "Even when you want things to be better, make sure it's for the betterment of those that you are also taking from.”

Earlier this year, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton sided with property owners, asserting that Texas Central hasn’t demonstrated that it is a “railroad company” or an “interurban electric railway company” authorized to exercise eminent domain under the Transportation Code. Paxton wanted the Supreme Court to understand that Texas Central isn't currently operating “anything resembling a railroad.” He went on to say Texas Central “failed to establish” a likelihood that it would succeed in getting the capital for the high-speed train.

The farm serves as an event center for things like weddings and Juneteenth celebrations, and it’s also an educational place to teach about the African American experience in Texas. The farm has several houses that replicate post-Emancipation times, filled with artifacts and history.

“Ultimately, the Emancipation Proclamation took place, then you have people that were living post-Emancipation Proclamation. The things that they had in their homes, how they lived, those are important parts of all of our stories. So that's what I want people to know to come and do tours and learn about the history and the richness of the African American experience in Texas,” Berry said.

Berry doesn’t want to see the history on this land become fractured to make way for something that’s not for the betterment of her family.

“Being from Texas, land is so important. It is the one thing that you can count on, just like you can count on your rifle, you know? So for somebody to want to take a right to own land and use it at their own discretion without any notification, I mean, you guys got to come up with a better plan,” Berry said.

In early June, the Texas Central CEO, Carlos Aguilar, left the company, saying he was not able to align the current stakeholders on a common vision for a path forward. However, Aguilar wished the project success and is convinced it will benefit all Texans. The board of directors has also disbanded and the company is being managed by FTI Consulting, which did not respond to requests for comment.

The project is estimated at $30 billion, and Berry is hoping the funding for the train never actually comes, and the whole project fizzles out before construction begins.