FLORIDA — Florida’s beauty is what makes it paradise, with its blue Gulf waters and sugar sand beaches. But it’s also this very locale — in a state surrounded by more than 1,300 miles of coastline — that makes us susceptible to the impacts of climate change.

Living in the Sunshine State, we know what kind of weather to expect most of the year. But even that is changing over time, as climatologists note small differences in the average weather conditions meteorologists like ours references in their weekly forecast.

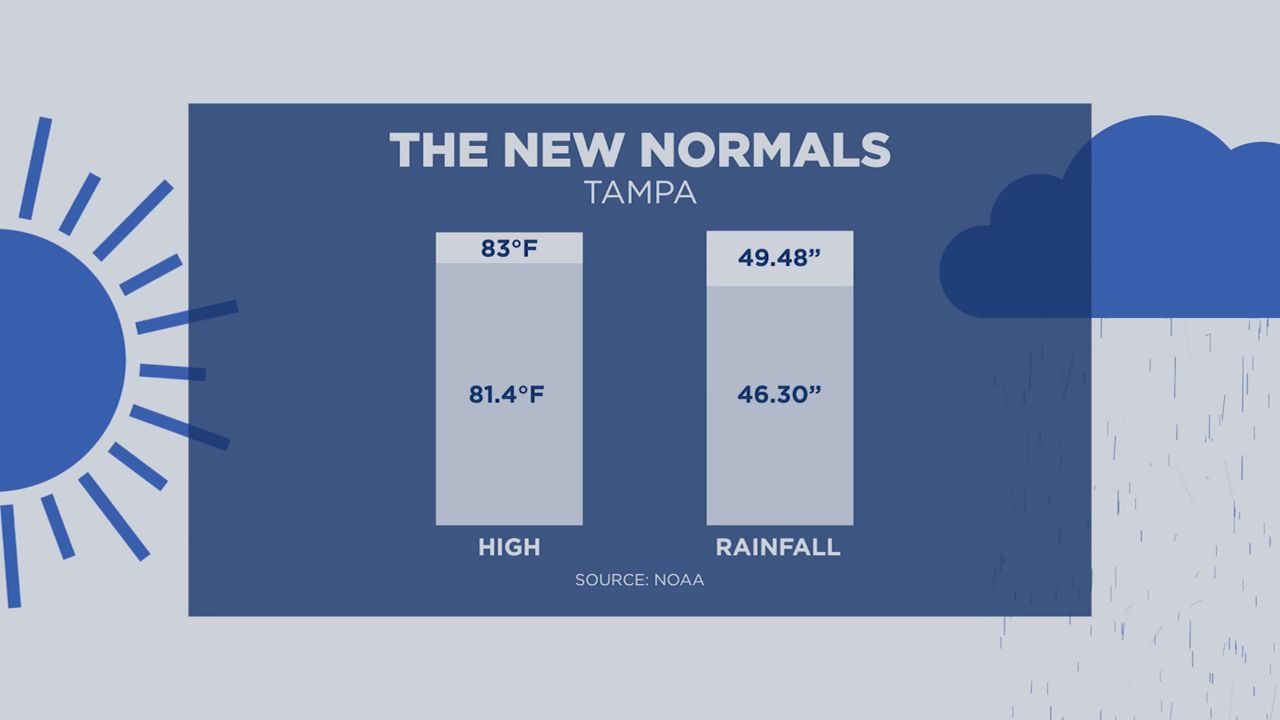

“The National Weather Service has a climate center in North Carolina, and every decade one of their duties is to look at the average over the last 30 years at all of these weather stations all over the United States,” said Spectrum Bay News 9 Chief Meteorologist Mike Clay. “And from that, they come up with what they call the normals.”

Those “new normals” act as a baseline that puts the forecast into perspective for viewers at home.

The most recent numbers were released in May. That data shows Tampa’s annual average high jumped from 81.4 to 83 degrees Fahrenheit, and the annual average rainfall from 46.30 inches to 49.48.

“To the normal person, you probably don’t even notice it,” said Clay. “But as a climatologist would look at that, they would look at tons of data over decades and decades. And if you start to see a departure of one or two degrees, then that is significant.”

Gary Mitchum, a professor of Physics Oceanography at USF’s College of Marine Science, explains how these seemingly small increases lead to big changes in precipitation levels.

“The thing that concerns me most about rainfall patterns is if the air is warmer. Even if it doesn’t increase a lot, you have more potential for very high rain rates,” said Mitchum. “There’s just more water in the air, in an absolute sense. Those are the kind of downpours that are going to affect our ability to run the water off. We don’t just worry about sea-level rise flooding now. We worry about rainfall flooding. We’re being hit from both sides.”

Mitchum said this will play a role in future storm systems.

“There is good evidence that we’re going to have storms that are slower moving and very heavy rain producers,” he said.

Consider the unprecedented and deadly flooding of Hurricane Harvey in 2017 as it stalled over Texas for days. And just this summer, remnants of Hurricane Ida dumped record rainfall in parts of the northeast, leading New York City to declare its first-ever flash flood emergency, as water-filled subway stations and covered major highways.

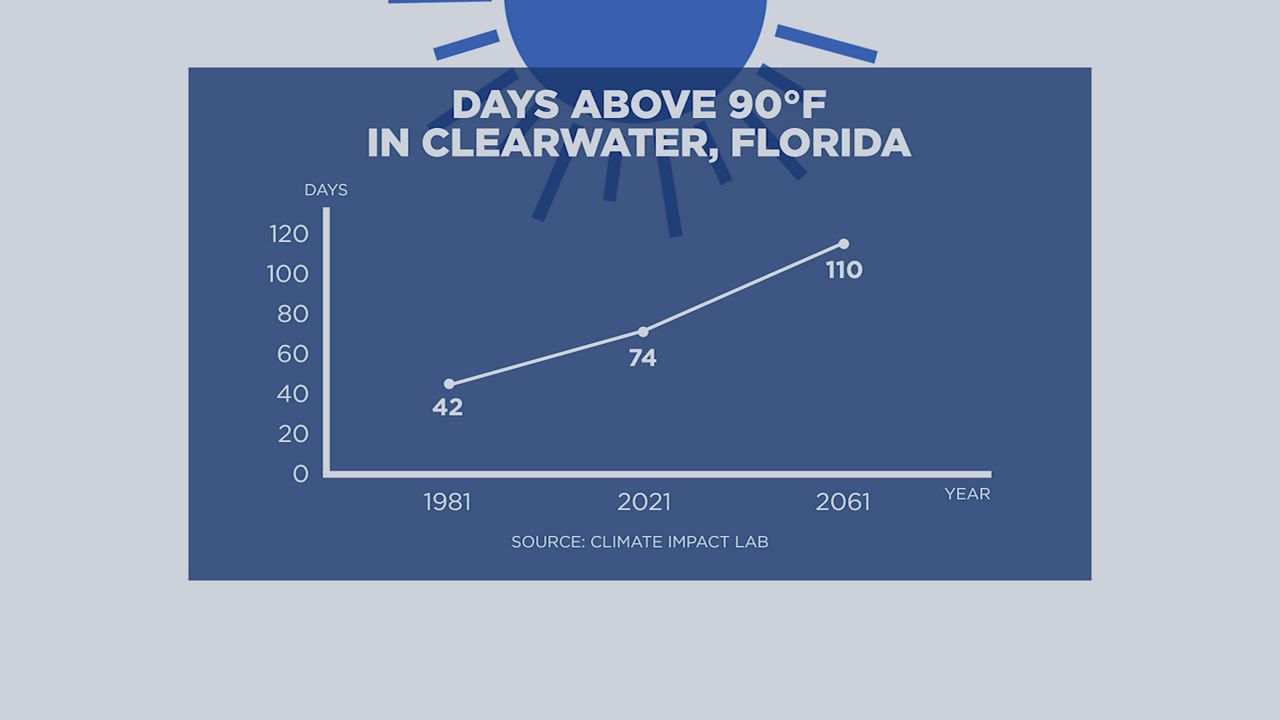

“As we look into the future, the new normal is going to be that all of the things are predicted to be more frequent,” said Mitchum.

Experts say an increase in rain rates will also lead to flooding during more regular, summertime storms.

“Our systems were designed at a time that had certain conditions,” said Claude Tankersley, Public Works Administrator for the City of St. Petersburg. “The Bay is at least eight inches higher than it was back in the 1940s. And eight inches doesn’t sound like a lot, but in such a flat area as we are, eight inches can mean the difference between a street flooding every now and then, or not.”

Claude describes a system of stormwater pipes that are installed at a slight angle, so gravity can guide water entering at one end out the other into Tampa Bay. If the bay rises, covering some, if not all of the pipe, the outflow is harder. Add more rainfall and the problem becomes even worse. With an intricate system of pipes all connected, neighborhoods miles away could be affected.

“You might have a street that in the past would flood maybe once a year for maybe an hour during a storm. Now it’s flooding maybe six times a year for two hours,” Tankersley said. “And so that’s going to be the conversation we have to have with the public. What is more important to you. To have a street that never floods ever? And if that’s what’s important, are you willing to pay millions and millions, if not billions of dollars to reach there?”

The cost would total about $3.2 billion over 20 years, according to an assessment that took into consideration all of St. Petersburg’s aging water infrastructure.

Across the bay, the city of Tampa already approved and started its own plan with just a slightly lower price tag that will ultimately double water rates by 2028 to help pay for it.

It’s important to note that data had to be collected and assessed before developing any sort of plan, and now, bipartisan legislation passed just this year will help other cities do the same through grant money from the state. Florida will also be required to have a statewide plan by the end of 2023.

In the thick of it will be USF’s College of Marine Science, as the legislation also establishes an on-campus hub that will help coordinate the efforts.

“I think the future is bright in a fashion,” said Mitchum. “The science is getting better so we can assess the impacts. If you know the impacts and you know what’s coming, then you can figure out how to prepare. The worst thing you can do is ignore it and say I don’t believe it or there’s nothing we can do about it.”