FLORIDA — Hidden underneath the ocean waters is a beautiful world of intricate ecosystems that are endlessly intertwined. Now, experts say that delicate balance has been interrupted by the rising tides and temperatures of climate change.

“Florida has the third-largest barrier reef in the world. A lot of people don’t realize that. And it’s along our Atlantic south coast,” said Dr. Deborah Luke, Senior Vice President of Conservation at the Florida Aquarium. “So where we are right now, that barrier reef is doing exactly what its name says. It’s a barrier. So when you think of tidal flow and impacts from the ocean, it does an amazing job. If we didn’t have those reefs, the impacts of the storms would be so much worse than they are already.”

Coastline protection is just the start. Coral reefs serve as a nursery and feeding grounds for hundreds of thousands of different aquatic species — an ecosystem that directly impacts the world’s food chain, right on up to the commercial fishing industry that feeds us. Tourism too, with NOAA valuing the reefs in Southeast Florida at 8.5 billion dollars worth of economic impact. Simply put, the ripple effect of coral loss would be devastating both in and out of the water.

“Climate change is affecting reefs in a variety of different ways. The first and foremost way that we see the biggest impact is with the changing water temperatures,” said Dr. Luke. “Corals have symbionts which are algae that actually live in with the baby corals and adult corals. It’s what gives the coral its colors. And when the water gets warmer, those symbionts move out of the coral. That’s what causes coral bleaching. We’re seeing a lot of that. Not only here in Florida, but we see it around the world.”

That makes the conservation efforts by The Florida Aquarium more urgent than ever before.

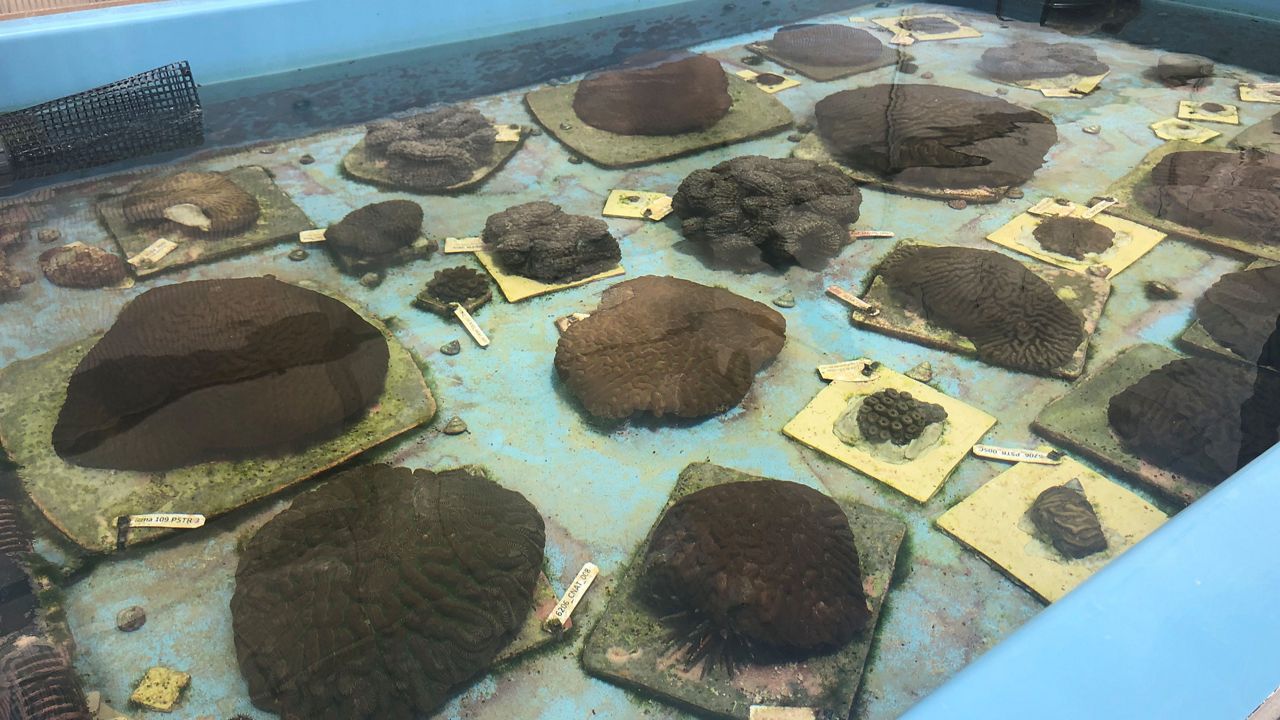

“What we’re really excited about is we have our induced spawning laboratory here where we have tanks that we put corals in, and we have artificial lighting in there,” Dr. Luke explained. “LED lighting that’s all computerized. So it matches the environmental conditions of the Florida Keys. We mimic water temperature, salinity, we mimic moon cycles every day. And what we’ve been able to do in the past three years is induce the coral to spawn at the exact time it’s spawning in the wild.”

The coral babies are then raised in coral greenhouses. It’s a slow but rewarding process that ends without planting at sea of what Dr. Luke calls more resilient corals.

“If we know that coral A seems to do better in warmer waters, we can breed it with coral B and see if AB babies are a little bit more resilient to warmer waters. And that’s really a key component,” Dr. Luke said. “We can raise all the corals we want here, but if we put them back out there and they don’t survive, why are we doing that? The key is we need to be on the forefront, cutting edge, and that’s what we’re doing of looking at how to make corals more resilient and protecting them along the way.”

And in turn, protecting the biodiversity of an underwater ecosystem that includes yet another species being looked after at the aquarium’s Apollo Beach location.

“A lot of the impacts we see with coral reefs due to climate change, we’re seeing impacts with all different species and sea turtles are no exception,” Dr. Luke said. “Sea turtles migrate, and they use very strong currents that typically follow migration patterns each year. And what we’re seeing is, as the water warms, those currents are changing, which means the turtles change directions and move but there may not be the prey species they need there."

This year, the aquarium rescued a record number of turtles by June.

“We’ve doubled our capacity,” Dr. Luke said. “Typically, we bring in about 30-35 a year. We’ve brought in 32 already.”

Many were cold-stunned and fighting for survival when they arrived from as far away as New England.

“What we’re seeing is shifts in when it starts to get cold. We’re also seeing, depending on where you live in the country, where some places are getting colder,” Dr. Luke said. “It’s climate change. It’s not just global warming. It’s climate change.”

And it’s impacting all of Florida’s five species, each listed as either endangered or threatened. It’s a status made worse by Florida’s eroding shorelines, due in part to rising tides and intensifying storms.

“That’s where sea turtles nest. That’s where they lay their eggs,” said Dr. Luke. “If they come up and there’s nothing to lay eggs on, they don’t lay them. It only takes a couple of years to realize that species is all gone.”

Since 2015, Florida has spent more than $329 million on beach restoration projects statewide, including more than $60 million in the fiscal year following Hurricane Irma. Honeymoon Island in Dunedin, the busiest state park, just underwent its second project since that 2015 benchmark. Officials said it wasn’t even possible for sea turtles to nest on the 3,000-foot stretch that was worked on.

In the latest round of funding for this issue, the state announced $100 million in the new state budget, along with an allocation of $50 million in federal stimulus dollars, all earmarked for rebuilding beaches.

Here in Tampa Bay, local efforts are underway as well. But rather than renourishing what already exists, volunteers can create brand new ecosystems.

“Our mission has kind of evolved from just bringing oysters back to reducing erosion on many of the shorelines around Tampa Bay. One of our methods is creating living shorelines,” said Richard Radigan, the shell coordinator with Tampa Bay Watch.

First, oyster balls made of marine-friendly concrete are installed to break up the waves hitting the shoreline. Next, bags of oyster shells are stacked, in the hope that oysters will attach and form a new habitat. Finally, the last layer of each project is seagrass, completing a new carbon-friendly ecosystem.

“When you establish these oyster reef balls and then the shells and then the grass, you are giving habitat to a large number of species,” said Radigan. “It’s such a beneficial area in the environment that if we can establish more and more of these, that only helps the water quality in Tampa Bay as a whole.”