RALEIGH, N.C. — Even after serving as the state's attorney general and its secretary of state, Rufus Edmisten said the most important moment in his political career was his role in the Watergate investigation.

What You Need To Know

Friday marks 48 years since the Nixon White House was subpoenaed for the release of the president's recorded conversations

Rufus Edmisten was assigned to deliver the subpoena to the White House

The subpoena marked a turning point and ultimately led to President Richard Nixon's resignation

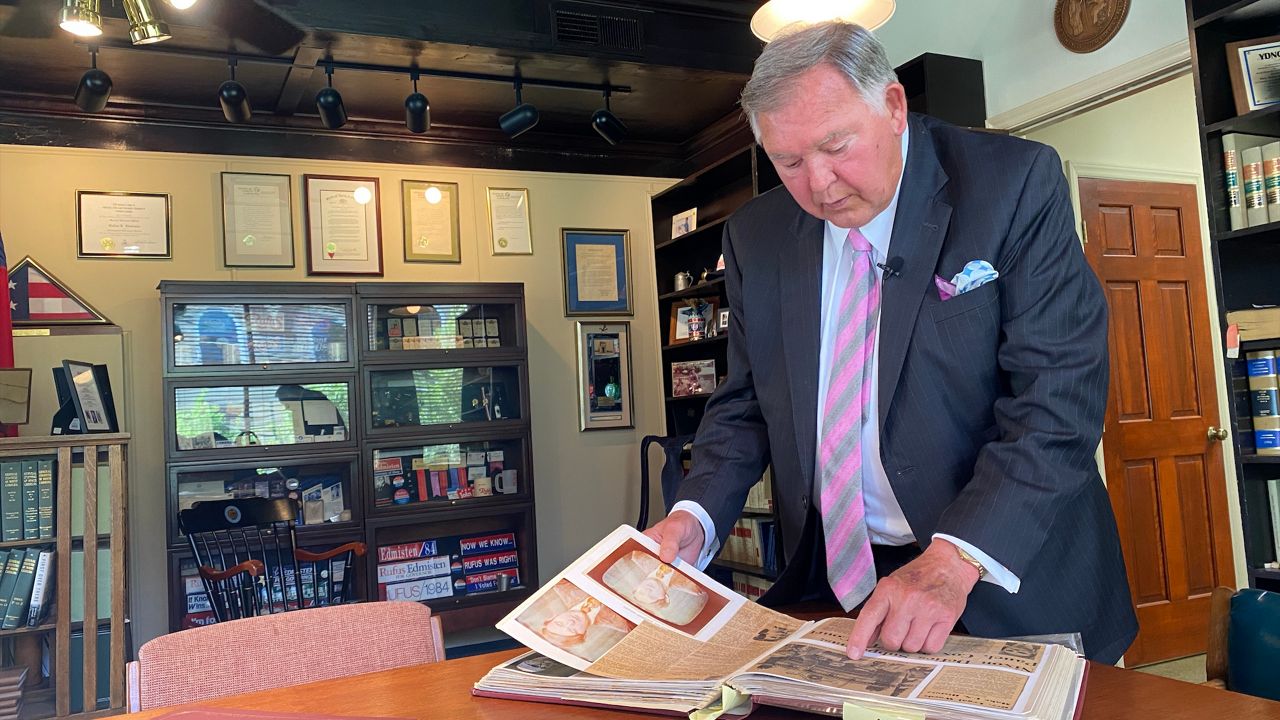

Leafing through his collection of photographs and newspaper clippings five decades later, Edmisten can instantly point out the major players in the Watergate saga: White House Counsel John Ehrlichman; Fellow White House Counsel John Dean; Director of Central Intelligence Richard Helms.

“Hard to believe. Fifty years ago and I'm still standing on two feet,” Edmisten said.

When a Senate committee convened in early 1973 to investigate any potential ties between the Nixon Administration and the previous year's burglary at the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate Hotel, North Carolina Sen. Sam Ervin was put in charge. By then, Edmisten had served on Ervin's staff for a decade.

“I learned more from Senator Ervin in one day driving him around, as I did for 10 years, than I did in my entire law school,” Edmisten said of his former boss and mentor. “That's how great he was.”

Edmisten said the committee shared a bipartisan determination to get to the bottom of the Watergate issue, regardless of party. It was the committee's Republican vice chair, Sen. Howard Baker, who asked the now-famous question, “What did the president know, and when did he know it?”

“Howard Baker was not one who was trying to cover up for the president,” he said. “The White House didn't like that he was doing that, and they were very aggravated about it.”

As deputy majority counsel to the committee, Edmisten had a literal front-row seat at the hearings. In photographs from the time, he is frequently visible sitting between and just behind Ervin and Baker.

“The hearings were covered up every day with a waiting line of people wanting to get into the Watergate hearings out on the street,” he said. “Watergate was a drama. It had everything you could think of. Intrigue, dispute, political skullduggery.”

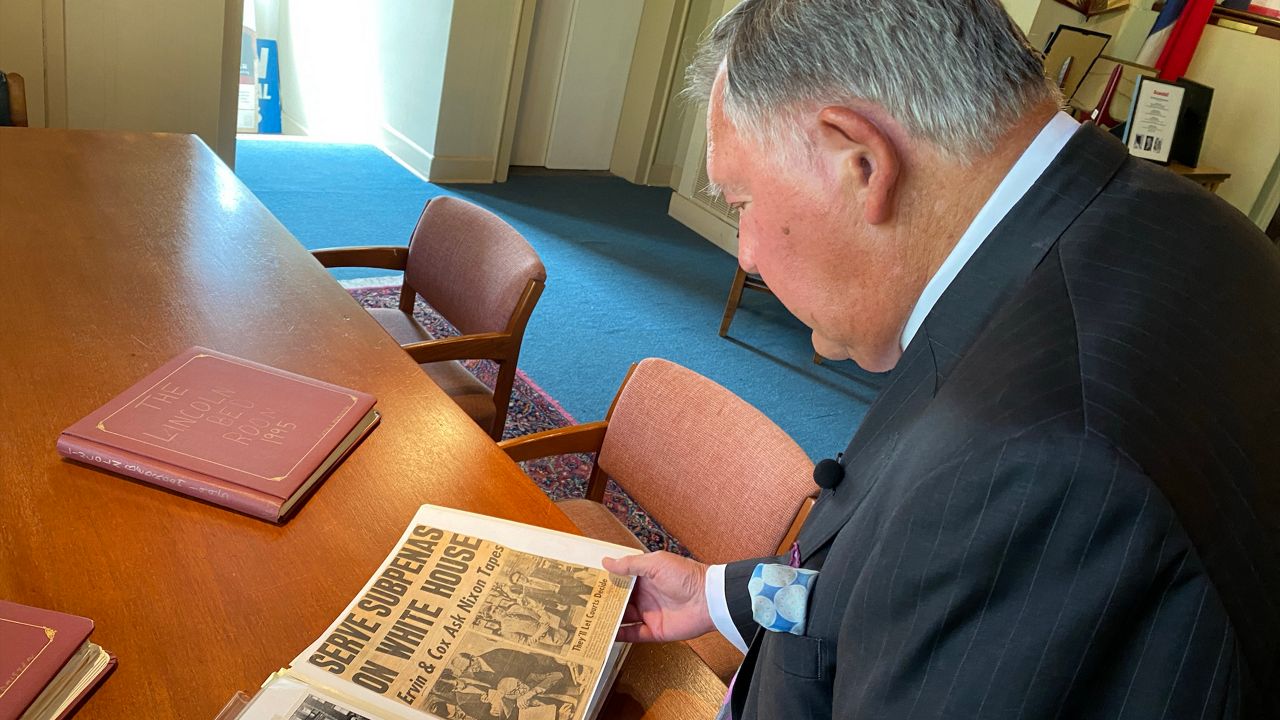

The pivotal moment came on July 16, 1973. Under questioning from minority counsel and future U.S. Senator Fred Thompson, presidential assistant Alexander Butterfield revealed President Richard Nixon had installed a system of tape recorders at the White House to record his conversations.

“It was the beginning of the downfall of Richard Nixon,” Edmisten said. “We knew if you could find from the tapes that Nixon knew about Watergate and had committed all of these coverups, that he would be guilty, and that we would have solved our case.”

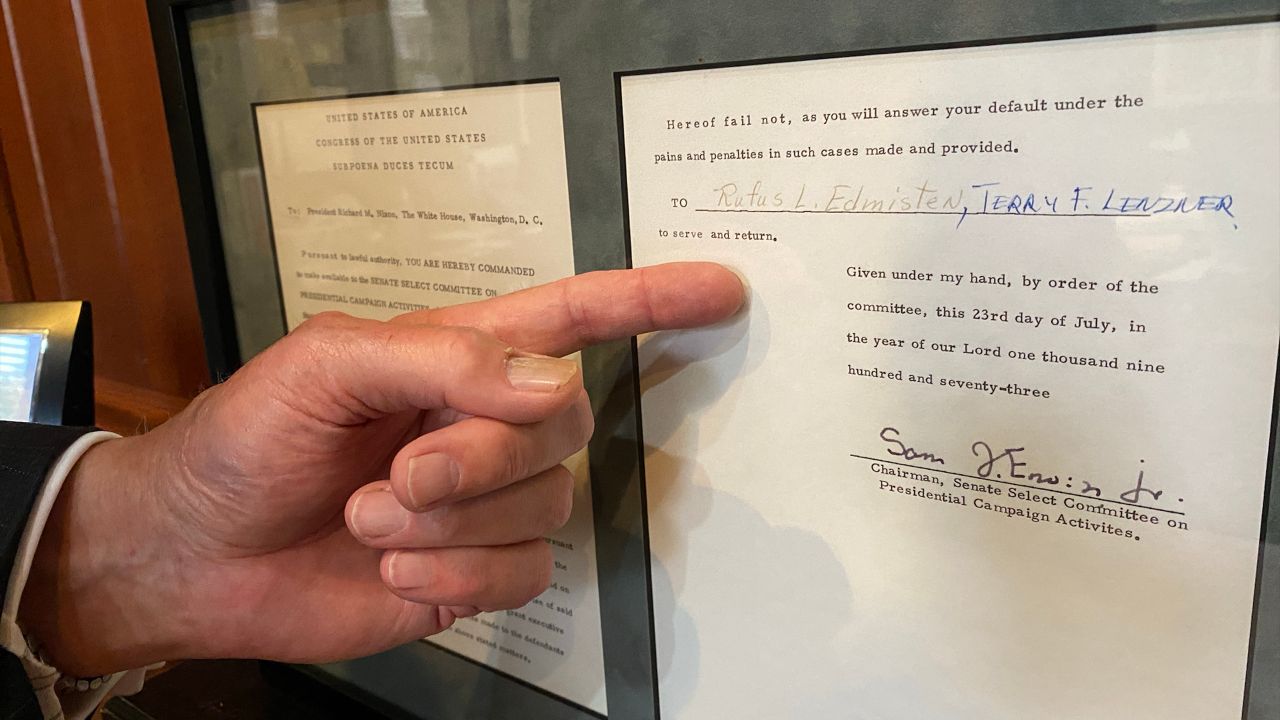

The committee's staff began writing a subpoena to get the tapes. By July 23, it was ready to go. Edmisten would be the one to deliver it. Now displayed next to his desk in his Raleigh law office, the document still bears a mark where a mistake was blotted out. Edmisten recalls asking the secretary who wrote it if she was OK with it having the correction on it. She replied curtly that she had already typed up the document three times and had no intention of doing it again.

Edmisten rode to the Eisenhower Executive Office Building across from the White House that evening in a police car. A copy of the envelope he carried bears the time of delivery: 6:25 p.m.

“There to meet me was the president's legal counsel, and I said, 'I have a subpoena here from the Senate Watergate committee that I have been ordered to serve on the President of the United States of America.' And the White House counsel quipped, 'Well you just missed the president. He was here a couple of minutes ago,'” Edmisten said. “And I thought, well, wouldn't that have been something to hand the subpoena to the president?”

It took another year and a Supreme Court ruling before the tapes were finally released. Once they were, recordings revealed Nixon had no role in the burglary itself but had worked to cover it up once he learned of it. One recording included him discussing having the director of the CIA ask his FBI counterpart to call off the investigation on the ground that the Watergate break-in had been a national security operation. Edmisten said it was the coverup that sunk Nixon, not the crime itself.

By the time Nixon resigned, Edmisten was winding down his time in Washington. Ervin was leaving office, and Edmisten was busy with his ultimately successful campaign for North Carolina attorney general. Edmisten would serve a total of 10 years in that office and another eight as North Carolina's secretary of state, along with an unsuccessful bid for governor in 1984.

He continues to practice law in Raleigh. The subpoena he served is now displayed just feet from his desk in a special shadow box. One of the gavels Ervin used in the hearings is mounted on the wall just outside his door. When asked what was the most significant moment in his career, Edmisten said it undoubtedly would be his role in the Watergate hearings.

“(Watergate) was the one crisis in America, probably next to the Civil War and maybe the two World Wars that shook up government the most, that laid bare how our system works, and it showed the system did work,” he said. “I had a tiny little part in making that happen.”