NEW YORK CITY — New York City quietly reopened traffic courts last month with coronavirus safety measures that fail to protect drivers’ health or their right to due process, critics say.

While safety measures for motorists are limited — bathrooms go unclean, plexiglass barriers and hand sanitizer stations are scarce — NYPD officers are allowed literally to phone in their testimony, photos show and the Department of Motor Vehicles confirms.

That right is not extended to motorists, who can submit written testimony should they decide not to appear.

The motivation behind rushing back drivers, and not officers, is likely financial, said Bhairavi Desai, director of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance.

“It’s a revenue generator,” Desai, head of the 21,000-member union, said. “No New Yorker should be denied due process all so they can make more money off poor people.”

Seven of eight TVB offices — administrative courts where traffic tickets can be contested — reopened across the five boroughs within the past month, according to a DMV spokesperson.

The single exception is the Brooklyn North bureau, which sits in the Atlantic Terminal Mall closed by Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s phased reopening protocols, the spokesperson said.

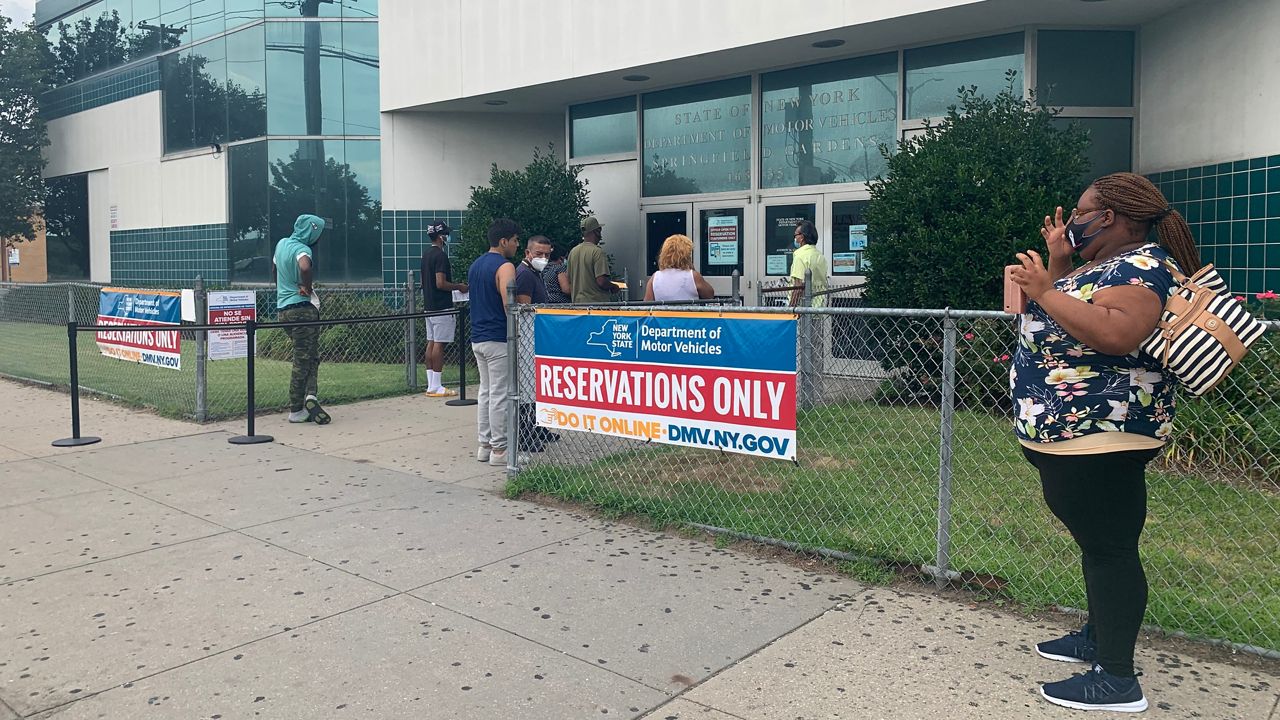

Only drivers with scheduled hearings or reservations — and attorneys representing them — are allowed in the Traffic Violations Bureau, where floors are marked to encourage social distancing, according to the DMV.

"The DMV has taken broad steps to ensure safety in our hearing rooms including limiting in-person contact whenever possible, which is paramount in the midst of this pandemic," the spokesperson said.

But photos taken at the Queens South bureau show a dense line of motorists forming outside the building, and a single piece of plexiglass hanging between judge and clerk, but not judge and driver.

“You can just walk in and walk up to anyone,” a TVB bureau attorney said. “Someone is going to get sick, it’s just a matter of when, not if.”

A single hand sanitizer unit is mounted on the wall and only one bathroom, where urine commonly pools on the floor and paper towels frequently run out, is open to the public, the attorney said.

“It’s filthy,” the attorney said. “You cannot go in there.”

Yet the COVID-19 safety precaution that worries the attorney most is not one that hasn’t gone far enough, but one she and Desai believe has been taken too far.

Traffic cops, who act as prosecuting officers, call into hearings and share evidence over the telephone, a right not extended to motorists, the DMV confirmed.

"For everyone's safety, neither law enforcement nor motorists are required to appear in person," the DMV spokesperson said. "If an officer fails to appear by phone or provide sufficient evidence to sustain the charge against the motorist, cases are dismissed just as they always have been."

NYPD officers are not allowed inside the bureau because of high infection rates the force exhibited in March, which were about 20 percent, the attorney explained.

But that rate dropped to about 10 percent by mid-May, which at the time was half the city average, according to Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s office.

“Legally, they are breaking and bending every law to entrap motorists into being found guilty,” the attorney said. “This is the state’s piggy bank.”

The Queens South bureau, which she estimates is operating at 50 percent capacity, brings in about $10,000 to $20,000 in fines a day with about 160 cases on its daily docket.

Fines collected first cover New York State operating expenses with remaining funds going to the areas where violations occurred, according to DMV policy.

That may be why New York City’s 2021 budget includes plans to increase summons issued from a projected $550 million to at least $592 million.

“This is a complete money-making scheme,” the attorney said. “And there are thousands upon thousands of people who are going to pay the price.”

While new rules allow motorists to submit written testimony, both Desai and the attorney said the system is difficult for drivers to navigate and the consequences of a mistake are often a guilty verdict.

Police mistakes can prove costly as well. It’s not unheard of for police to incorrectly transcribe a license number and summon the wrong driver to court, yet it's impossible to disprove if the officer cannot see the defendant, Desai said.

The phone-in sessions also rob judges of valuable information, things as simple as body language and as fundamental as the chance to see an officer's notes, Desai and the attorney said.

“It had a real impact on the drivers,” Desai said. “More people were found guilty.”

A recent study from the New York Law School’s Racial Justice Project found low-income New Yorkers are disproportionately burdened by those summons because those who cannot afford to pay their tickets can see fines accumulate and suspensions become permanent.

For Taxi & Limousine Commission drivers, a suspended ticket license means an income already depleted during the pandemic comes to a screeching halt, both women noted.

“These are the way that the states really taxes the working class,” Desai added. “Michael Bloomberg isn’t getting pulled over for violations.”