Each year, through every season, millions of Americans visit the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.

“What's nice about the wall, I think every veteran that visits maybe gets something different out of it," said Bill Walters, a volunteer at the memorial and a Vietnam war veteran. "But it's nice to have a place where you can come and we're all kind of kindred spirits, we all have similar backgrounds, and it's a good spot."

On a crisp fall morning, Walters and another volunteer veteran are answering questions from visitors, watching as a group of students walk along the wall, some of them running their hands over some of the over 58,000 names engraved on the black granite slabs.

“I think the younger generation gets some of it, I don't know that they get it all. But for the most part, they're overwhelmed by the number, the 58,000 number,” explained Walters. “As they learn more about the details of the war, and almost everybody knows of someone or knows someone, it hits home pretty good.”

While the wall has become a staple to visitors from across the country and around the world, the memorial was only erected 40 years ago, marking its anniversary this Veterans Day. The idea to build a monument was originally proposed by combat veteran Jan Scruggs, who partnered with lawyer and fellow veteran Robert Doubek to start the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund (VVMF).

“To build a memorial on the mall, we found out we needed an act of Congress. And fortunately, Senator [Charles] Mathias of Maryland was willing to introduce that act of Congress because he said that while he opposed the war, he had always supported the veterans,” recalled Doubek. “So we had an act, a bill introduced in the U.S. Senate. And then of course, we had to begin to raise funds.”

Virginia Sen. John Warner helped the VVMF raise the original seed money, but the rest of the funding for the project was raised by American contributions through a direct mail campaign. Americans sent over $8 million dollars to build the memorial.

On July 1, 1980, President Jimmy Carter signed the legislation that provided the two acres on the National Mall where the memorial currently sits.

But the work was far from over; then they had to design the memorial.

“Since there were so many people inquiring, there's so many people out there who are already wanting to offer their services to design it,” said Doubek. “We [decided] that the fair way to do it, we’d have national competition.”

With 1,421 entries, Doubek says “it turned out to be the largest open design competition ever held in the United States or Europe.” The VVMF had to use an aircraft hangar at Andrews Air Force base to display the designs for the judges to view the entries.

The committee chose the design of 21 year old Maya Lin, then an undergraduate at Yale, for the project. Her design of two black walls rising from the depths of the earth with the names of those who died during the war aimed to create a “personal” connection.

“I wanted to say something about making this memorial personal, human, and focused on the individual experience. I wanted to honestly present that time and reflect upon our relationship to war and to loss,” she wrote on her website of the design. We reached out to Maya Lin for this story, but our request for an interview went unanswered.

As the monument was constructed, Doubek was there each day, watching the machinery dig into the earth, and the memorial took shape before his eyes.

“The impetus for the memorial was to counter the extreme psychological … negativity that the veterans encountered when they came home. They did not return to a supportive psychological atmosphere. And so basically, some had to pretend they hadn’t gone through traumatic experiences,” said Doubek. “They couldn't talk about it.”

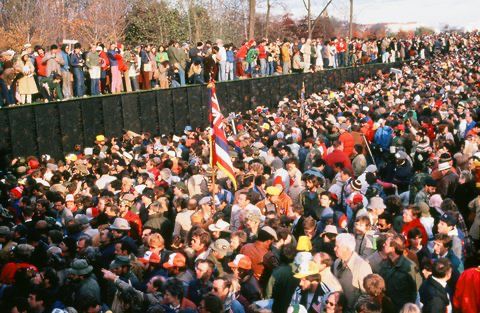

Construction on the monument began in March of 1982, with planning of the memorials dedication set for Veteran’s Day that fall. The project was completed in October, and then dedicated on November 13, 1982.

Some veterans were outraged by the absence of patriotic or heroic symbols, but that anger soon faded, as the memorial’s simple design came to be seen as a way to encourage reflection and healing after a hugely unpopular war.

“The day we opened it, there were people here and the quiet was remarkable. It felt like you were in a church or a temple. It was just there was such a tremendous sense of reverence,” remembered Doubek. “We heard from a lot of veterans, because there had been so much negative publicity, they were prepared to dislike it. People change their opinion as soon as they were here and they experienced it.”

Forty years later, Doubek says he feels the memorial has been able to meet the goal they set out to achieve so many years ago: to provide peace and healing.

“It is very moving to see that this memorial has a tremendous longevity,” said Doubek, as he walked along the memorial, pointing out features of the design. “I think what really makes this memorial special is the inscription of all of the names because it personalizes it to such a great extent, and gives visitors many, you know millions of visitors, a connection point.”

As Doubek walks us down the path along the wall, he stops and shakes hands with Walters, asking him how he’s been. Doubek knows most of the veterans by name who give their time to teach visitors about the monument he helped to build from the ground up.

Walters, who spends a couple days a week in the shadow of the monument, says it’s important to continue sharing the story of his fellow veterans, and those who did not make it home.

“What I tell the school groups when they visit is ‘when you folks are running the country, just remember, it's harder to get out of a war than it is to get into it.’ And I'm not sure if that really hits home just yet, but it will at some point.”

But Walters says he is glad to see the attitude towards those who serve our country in uniform change from nearly 50 years ago when he returned from Vietnam.

“People are sometimes mad at the warrior, not the war," Walters said. "And now we seem to have great respect for the people that are serving no matter what your politics are.”

If you would like to experience the Vietnam Veterans Memorial for yourself, you can take a virtual tour here. The memorial also has an online collection for the public of items left at the wall by visitors that you can experience here.

If you’re interested in becoming a volunteer at the memorial, you can contact the National Park Service, or apply online.