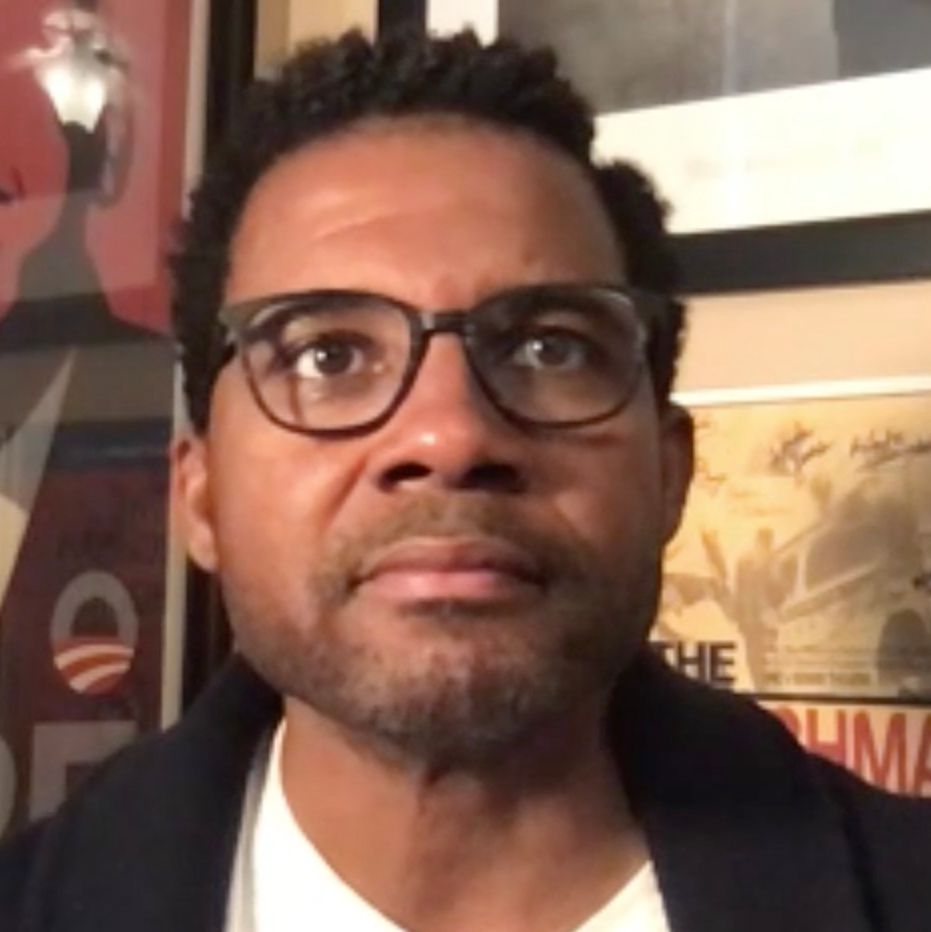

Raleigh, N.C. — From the stage, Mike Wiley will face a wall of screens spanning the theater, his audience of 150 Zoom windows looking back at him.

In his one-man play Breach of Peace, Wiley won’t just stand up in front of the camera at Raleigh Little Theatre. He will be able to interact with the audience and bring them into the production, even if they can’t actually sit in the seats in front of him.

“As big as I am to them, they are as big to me. It’s like being with a live audience, it’s like having folks in the room except they’re sometimes in their PJs,” Wiley said. “It’s the magic of theater in these COVID times. “

Wiley is a North Carolina-based playwright and actor. He will be performing Breach of Peace, about the Freedom Riders’ journey to the South in 1961 to help register Black voters. The characters in the documentary-style plan include Civil RIghts legends like John Lewis and Stokely Carmichael.

“Beach of Peach is about those first few days of them getting on separate busses in D.C. and riding into the deep South and the experiences they had along the way. The experiences of gratitude from some and the experiences of hate and violence from others, eventually landing them in Parchman Prison,” Wiley explained.

“The play stops as they pull into Jackson in their buses after having seen so much violence in Montgomery, Alabama and Birmingham, Alabama,” he said.

Breach of Peace will broadcast by Zoom from the Clayton Center at Raleigh Little Theatre Friday and Saturday at 8 p.m. Tickets are $25 and available from Raleigh Little Theatre.

Much of Wiley’s work deals with difficult subjects in American history, including slavery, lynching, and the civil rights movement. He did the theatrical adaptation of Tim Tyson’s Blood Done Sign My Name, about the 1970 murder of Henry Marrow, a Black man, in Oxford, North Carolina.

The coronavirus pandemic has forced theaters like the Raleigh Little Theatre to rethink how they work. The same is true for just about every other industry over the past year.

The theater, a couple blocks off Hillsborough Street near N.C. State University, has had to cut its budget in half, but they are still trying to produce plays for the community, even if they are over Zoom or taped.

“Normally, we are the ones who document dark times, right? So now we are left to document dark times at a time when our industry as well is in a dark place,” Wiley said. “We are doing our best as artists, as theaters, as filmmakers, as painters, visual artists, dancers to document this time while at the same time giving people hope.”

“This is a very different way of doing virtual theater,” Raleigh Little Theatre Executive Director Heather Strickland said in an interview this week.

They’ve been testing different ways to present theater virtually, she said. “This is one that really gets as close as possible to an audience being in a room with an actor.”

“Not only will the audience members be able to see Mike as he performs on a stage at the Clayton Center, but he will be able to see them,” Strickland said.

For Wiley, the audience is part of what can make a play really work. He said he learned that from working with a Shakespeare company some 20-odd years ago. In his other plays, he has brought people on stage to make them part of the action.

When there’s not a global pandemic, Wiley said he normally brings someone on stage during Breach of Peace to play the part of Martin Luther King Jr.

“Oftentimes, it’s a young Black woman,” he said. “What I’m trying to achieve is having the audience shift their paradigm. It’s having an audience look at it and look at the world from a different perspective.”

“At a time when we aren’t able to gather, but a time when we need to be able to talk about these issues, we need to be able to talk about these things, this is really an opportunity to see a production that is certainly from another period of time but speaks so deeply to the time that we live in,” Wiley said.

After a year of living through the global coronavirus pandemic, protests over racial equality and the Black Lives Matter movement, and intense political divisions, Wiley and Strickland said the theater and the arts will be even more important to process and understand what’s happened.

“Storytelling is going to be so critical to us moving forward,” Strickland said.

“The world is going to look different after this moment. It has to,” she said. “Storytellers are going to be such a massive part of that because it’s how we’re all going to understand how we did survive this. How we’re all going to understand not only our own experience, because we’re going to be able to identify with some stories, but also others' experiences.”